This year has witnessed a flurry of news articles about plans to end the HIV epidemic. Here’s a breakdown of three types of strategies and their goals.

“Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America” President Trump announced this federal initiative in February (set aside, if you can, the fact that his administration also aims to demolish the Affordable Care Act, remove insurance protections for preexisting conditions and allow discrimination against LGBT people, among other attacks on health care). The federal initiative’s goal is to lower HIV rates nationwide by 75% in five years and by 90% in 10 years.

How? One way is to channel federal resources to the 48 counties (plus Washington, DC, and San Juan, Puerto Rico) that account for more than half the new HIV cases in the country; in addition, seven states with a high proportion of HIV in rural areas will also receive federal help. These are Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma and South Carolina. The federal plan focuses on four key pillars—diagnose, treat, prevent and respond—and uses current HIV data to identify where the virus is spreading so resources can be deployed quickly.

Robert Redfield, MD, who leads the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has been traveling to these HIV hot spots to discuss Trump’s plan and how local communities can collaborate. The Cherokee Nation is already a partner.

This year’s United States Conference on AIDS (USCA), held in September in DC, focused on the federal plan and how jurisdictions can set up their own plans in order to qualify for federal funding. During a plenary discussion with Redfield, protesters stormed the stage and voiced concern about the government’s collection of HIV surveillance data, especially in states that criminalize HIV.

Meanwhile, the policy and advocacy group AIDS United offers its expertise to communities seeking to develop, implement and strengthen plans to end their local HIV epidemics. In 2018, AIDS United released “Ending the HIV Epidemic in the United States: A Roadmap for Federal Action,” with the goal of ending the epidemic by 2025. Many of its elements were incorporated into Trump’s federal initiative.

Twitter/@MSNBCPR

90-90-90 Targets and Fast-Track Cities Launched in 2014 by the United Nations AIDS program UNAIDS, 90-90-90 programs and the related Fast-Track Cities initiative challenged cities and countries across the globe to achieve three goals by 2020: Get 90% of people living with HIV to know their status; get 90% of those who know their status connected to care and on antiretrovirals; and get 90% of those on HIV meds to reach an undetectable viral load. Zero stigma and discrimination is a fourth goal. Baton Rouge, Louisiana; San Antonio and Dallas; and Boston are among the U.S. cities zeroing in on these goals. A group of Alabama researchers and doctors aims to achieve the 90-90-90 targets in their state. And earlier this year, health officials in southern Nevada also took up the 90-90-90 challenge, though aiming for 2030, if not years before.

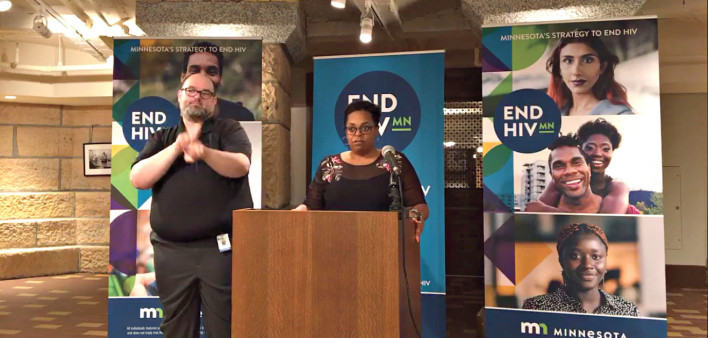

Local Strategies to End HIV/AIDS Many states and cities are creating their own plans to tackle their epidemics, often with goals similar to the federal and global initiatives. The past 12 months, for example, saw the launch of Minnesota’s “End HIV MN” and Connecticut’s “Getting to Zero CT.”

Since embarking on what became known as its “Getting to Zero” campaign in 2013, San Francisco has seen major improvements, including rapid declines in HIV rates. A recent report showed 197 new diagnoses in 2018, a low point for the city since the epidemic’s peak (though Black and Latino men and homeless people remain disproportionately affected).

In 2015, New York state officially launched the “Blueprint to End the AIDS Epidemic,” with targets including seeing no more than 750 new HIV diagnoses a year and lowering HIV-related deaths to near zero. Data from 2018 show a record low number of new HIV cases—2,481—and a huge jump in people on PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, to prevent HIV. This led Governor Andrew Cuomo to declare that the Empire State is on track to meet its goals by 2020.

Benjamin Ryan

Comments

Comments