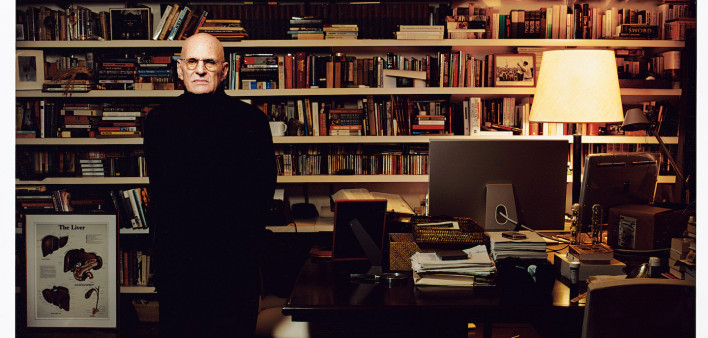

On a hill overlooking a pristine lake, in the library of his sprawling Arts and Crafts–style home, Larry Kramer toils to finish an epic novel—what he says will be the history of America as told by a gay man. Surrounded by stacks of thousands of manuscript pages, the man who invented AIDS activism is accompanied sometimes by his lover, the architect and designer David Webster, and always by his sad-eyed Wheaten terrier, Tiger. He’s been working sporadically on his book, The American People: A History, since 1979, before AIDS changed his destiny. Still, he says, “I’m a long way from being finished.”

It’s this project, not activism, that consumes him now. “If I don’t work for a couple of days, I feel awful,” he says. “Sometimes I’ll lie awake at night and won’t be able to think of a character’s name, and it drives me bananas.” He says he’s writing the book because he feels he must—and certainly not for the critics, who have long withheld the moniker of high art from his bluntly polemical books and plays. Kramer penned perhaps the most famous AIDS play, The Normal Heart, in 1985.

On this weirdly balmy December afternoon, he is unshaven and walks a bit slowly, but he’s far fitter than he was five years ago, before a challenging transplant for a liver ravaged by hepatitis B. He was among the first to show that HIV positive people could survive the procedure. At a time when many positive people feel it’s a miracle that they’ve lived beyond 50, Kramer, now 71, was already in his fifties when he was diagnosed with HIV in the mid-’80s. HIV never made him ill; his liver disease wasn’t directly related to the virus or its treatment. His miracle was the transplant; before it, he posed nearly nude for Newsweek, revealing a belly swollen by liver disease. He says he feels better than ever: “Some days I need a nap, but most days I don’t.”

Kramer writes nearly every day, rarely diverting attention from his novel (which posits, among other things, that George Washington was in love with Alexander Hamilton) and then only to fire off an e-mail of trademark outrage to, say, the National Institutes of Health or the New York Times—institutions he has long accused of indifference, at best, to the AIDS epidemic. Infamous for hurling verbal grenades in person, lately he has primarily launched e-mail attacks. “Don’t identify where I live too closely,” he says in a raspy voice from a rocker on his sun-porch. “I’m afraid somebody’s going to come and pop me, like the crazies on the religious right.”

These days, Kramer may be safer than he suspects. Tucked away in a posh town in Connecticut, the man who staged such spectacles as die-ins on Wall Street is no longer smack-dab in the crosshairs. His infamy is fading into history. In 1981, the year AIDS was first diagnosed, he co-founded the first AIDS organization, Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), in New York City. Kramer next sounded the clarion call for the shrewd, angry street-activist group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), which he co-founded in 1987. He and his anger-fueled, cop-confronting, FDA-busting, headline-grabbing gang showed that despised and feared “AIDS victims” could be fierce, strategic fighters capable of changing the status quo within government, medicine, Big Pharma and society at large. “We would not be where we are today had Larry not been there,” says Phill Wilson, the HIV positive founder of the Black AIDS Institute. “We have a great indebtedness to him.”

Despite his legacy, folks in power are less aware of Kramer these days. Since the early ’90s, when Kramer met Webster, and especially since his transplant, his presence in AIDS activism has been so limited that many young activists have no idea who he is. “Never heard of him,” said Johnny Guaylupo, 25, a member of the two-year-old national activist group Campaign to End AIDS (C2EA). Told who he was, Guaylupo said he thought he’d seen Kramer in a video on ’80s activism.

This year, however, young activists have seen a bit more of Kramer. In January, he attended an ACT UP meeting in New York. As POZ went to press, Kramer was scheduled to speak on March 13 for ACT UP’s 20th anniversary—commemorating his legendary 1987 speech that launched the group. And, on March 29, he was to participate in ACT UP’s anniversary action, set for downtown Manhattan.

He has also returned to GMHC, years after his fellow cofounders kicked him out because they found him too difficult. Kramer recently met with the organization’s current leadership to discuss getting involved again. He requested a lunch, in GMHC’s cafeteria, with its positive clients—many of whom are a world apart from those in his largely gay, white elite circles, a group synonymous with the early epidemic. Marjorie Hill, chief executive officer of GMHC, called the visit “a wonderful meeting,“ adding that Kramer “is an important part of our history, and his counsel is important to us today.” Facing what he calls the last chapter of his life, he’s deeply torn between finishing the tome that he hopes will seal his literary fame and staying involved with the activist world he has ambivalently left behind.

It’s an understatement to say that Larry Kramer can be difficult. He has branded several political heavyweights “murderers” for their alleged indifference to the epidemic—everyone from Ronald Reagan and former New York City mayor Ed Koch, whom many felt deserved that label, to longtime NIH AIDS czar Dr. Anthony Fauci, whom many felt didn’t. Dr. Fauci ended up collaborating with ACT UPers to hasten HIV treatments, and Kramer now calls him a friend. Dr. Fauci says, “[Kramer] has a style that rubs people the wrong way, but I totally admire the guy and think he’s done amazing things.” Dr. Larry Mass, an early chronicler of the epidemic, differs: “I reached my limit of tolerance [for him] … He’s a vilifier, a scapegoater, a person who assassinates characters.”

Kramer may initially appear gentler, but he hasn’t mellowed with time. “Certain people and things that I hated before, like Koch and the New York Times, I hate just as much today,” he says. “Anger is a very wonderful and positive emotion. Why should I want to let it go?”

What will his ACT UP anniversary speech bring? Consider “The Tragedy of Today’s Gays,” an address he delivered just after the November 2004 presidential election to a packed hall in New York City. He asserted that “as of November 2, gay rights are officially dead—from here on, we are going to be led ever closer to the guillotine.” He maintained that young gay men, instead of fighting for their rights, were destroying themselves with crystal meth and continuing to infect one another with HIV. He said they believed naively that the disease was no longer a problem, thanks to costly drugs so toxic that they amounted to “chemotherapy.”

The tough love inspired some younger gay listeners, such as Corey Johnson, 24, a Democratic Party consultant. “Larry slaps you upside the head when you need it,” says Johnson, who has cultivated a friendship with Kramer. But Johnson adds that, after the speech, “I told him, ‘People need something to motivate them, and you’re not giving them that.’” Many young listeners dismissed the talk as an apocalyptic rant, hopelessly out of touch with a better era for American gays and people living with HIV. “Like a general who fails to notice that the war has long since moved on to new frontiers, Kramer keeps beating the drums and waiting for people to show up,” the gay author Richard Kim, 31, wrote in Salon.

Kramer answers, “We’re not accomplishing anything [for gay rights]. We’re in a rut and we’re not getting out of that rut. For people like Kim to deny it is part of the rut.”

Even though AIDS has spread far beyond the gay population, Kramer repeatedly conflates AIDS activism and gay activism. A question about the former is often met with a critique of the latter. And some newer activists say Kramer can’t see that AIDS has increasingly become a disease of women, African Americans and the global poor. Phill Wilson says, “It’s difficult for the [black] constituents I work with to see Larry as the messenger. On so many different levels he does not resonate with them. And I’m not even suggesting that he’s trying to.”

A recent Kramer drama involving the New York Times suggests how his obsession with the epidemic’s past may influence his seeing it in the present. He has long loathed the Times because, he claims, “they wrote next to nothing [about AIDS] and treated gays with enormous disdain” in the epidemic’s early years. The paper invited him last summer to sit on a panel in New York City to discuss the evolving complexion of AIDS on its 25th anniversary. Wearing a T-shirt whose ACT UP–style black type screamed WHERE IS THE OUTRAGE?, Kramer interrupted everyone—including fellow panelists Dr. Fauci and the Foundation for AIDS Research co-founder Dr. Mathilde Krim—with a spray of doomsday pronouncements until several in the audience shouted at him to shut up. Kramer abruptly exited the stage, to scattered applause of good riddance.

“I thought, ‘I don’t need this—I’ve got other things to do,’” he remembers. He wanted to talk that night about what he considers the Times’ lousy record on AIDS coverage but said he felt that the moderator, Times editorial page writer Brent Staples wanted to discuss only the link between AIDS and injection-drug use. (Such drug use accounts for about a third of all U.S. infections but was not the only thing discussed after Kramer left.) Kramer says that after leaving, he walked home alone to his West Village apartment, almost returning several times. Why didn’t he? “I guess I didn’t care,” he says.

Drs. Krim and Fauci say they felt sorry for him. “He’s been so hurt [by the loss of so many friends] he can’t recover,” says Dr. Krim, even while adding that his “vision [of the epidemic] is the same” as it was 25 years ago and that he should “let AIDS be taken care of by other people who really understand it” scientifically. Says Dr. Fauci: “I wanted to whisper in his ear, ‘Larry, you have the wrong target. This isn’t an FDA meeting, the old days when you confronted Congress.’” Dr. Fauci adds, “I think when he was told to shut up, it hurt his feelings.”

Says Kramer, “I’m sure that was part of it.”

Would the world’s first great AIDS activist like to leave AIDS activism behind? His longtime best friend, Rodger McFarlane, who heads the Gill Foundation, which supports gay causes, points out: “Larry didn’t invite himself” to that Times panel. “I don’t think anyone would be more delighted in the world to retire himself than Larry.”

On this, Kramer seems conflicted. “I don’t miss being trotted out as the grand old man,” he says. “People are always wanting to give me awards at dinners and I say no to most.” Yet he says there’s a void in his life for active activism, a void computer activism just can’t fill.

If he does return more frequently to the activist arena, he may have to brush up on his facts. Kramer claims he’s kept abreast of activist developments, saying, “It’s interesting, don’t you think, that nobody younger has come along to do what I do?” But when asked about the thriving Student Global AIDS Campaign and C2EA, he says, dismissively, “I don’t even know what they are.” What about Health GAP, which has worked since 1999 to bring down HIV drug prices globally? “Once it’s set up, it becomes useless,” he answers. Told that Health GAP is an activist group, not an AIDS agency, Kramer says, “They are not confronting Bush, the government, the system.” And then: “I don’t see one single gay leader in politics or in AIDS activism who has the visibility or the voice that I had. I’m sorry.”

Julie Davids, an ACT UP Philly veteran who runs the national AIDS activist group CHAMP, counters: “The annual price of AIDS drugs going from $15,000 to $150 in several countries through generic production is a pretty distinct win,” she says, “and it wasn’t won by one person of stature but thousands of [activists] around the world.”

By e-mail, Kramer shares his opinion of the funding shortfall for the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) in South Carolina, where four people have died while waiting for HIV meds. His reply: “AIDS is not just on anybody’s radar of importance anymore,” he says. “Most of the main issues for many people have been more or less…solved … We have drugs … The biggest battle has been won. No wonder there is less interest (including by me) in the thousands of subsidiary problems, like this ADAP … [issue] you want me to comment on.”

When he’s pushed to share his feelings about South Carolinians dying from lack of access to care, his e-mails turn profane. They’re akin to his apoplectic response, back at his house, when asked what message, or activist guidance, he had for people more newly diagnosed with HIV. “I’m not producing the movie anymore,” he’d erupted. “You make me sound like a monster—like I’m not giving my love to everybody,” he says. “What am I supposed to do? I think I’m a nice person, a good person. I have a lot of good friends.”

Yet six weeks after the December interview, the picture is somewhat different. The man who e-mailed a testy admission of his relative indifference to Americans with HIV going without healthcare is now helping to steer ACT UP as they lobby for universal healthcare. Regarding Kramer’s involvement at organizational meetings for ACT UP’s 20th anniversary action, leader Mark Milano says, “He’s been quite involved.” Milano adds that Kramer “hasn’t been taking over meetings at all.” As we went to press, Kramer hinted that he might use his ACT UP anniversary address to announce an initiative linking gay advocacy and universal health care, making them front-burner issues for the 2008 elections.

He says he was profoundly moved during his recent lunch at GMHC. “There were so many people having lunch, and I knew so many of them. You see people who are still sick, and you also see that very few of them are white. I think that, for most people, the face of AIDS is invisible today.” Kramer says he’s helping the GMHC board organize the agency’s messy archives at the New York Public Library. He’d also like to see the group become a bit more brazen. “I told [Hill] she was too nice, and we had to get together and let a little of my style partner with her niceness,” he says, laughing.

Back in Connecticut, the strict two hours that Kramer had allotted for the interview have passed. He has boiled over in rage a handful of times. (Later, by phone, referring to some of the interview’s heated exchanges, Kramer would say, “You know why I got so angry? Maybe you touched on something when you asked if I feel guilty that I’m not involved anymore. I suspect I do. Although I didn’t want to be told that.”) But now he steps outside and offers a warm hug goodbye. In the final minutes on his porch, he says, “I think I’ve fought the good fight in terms of activism. I feel I’ve lived life well in the ways that are meaningful to me, and the book is my final accomplishment. I’ll put a record down on paper of what I believe about a great many things—about America, homosexuality, evil, disease, AIDS. It’s an enormous challenge—way, way, too ambitious.”

Could he be afraid of finishing it—afraid of the void that would leave? Some of his friends have hinted at that, he says. “It’s finished when it’s finished,” he laughs. “I’m not afraid of death. More afraid of dying before I’m ready.” Then, with Tiger at his heels, he turns—and disappears back inside.

Larry Kramer Ethan Hill

Kramer vs. Kramer

Polarizing ACT UP co-founder Larry Kramer faces a new generation of activists. Can he teach them a thing or two?

Comments

Comments