|

| Click here to read a digital edition of this article. |

In October 2009, David Bahati, a member of Uganda’s parliament, proposed an “Anti-Homosexuality Bill” (a.k.a. the “kill the gays bill”). It was an attempt to legalize a phenomenon spreading around the world: hate crimes against gay people.

During the past few years, there’s been an increased awareness around crimes against people who are gay. Many go unpunished. And as unjust as they are, these offenses have a secondary side effect. Namely, they backfire. Gay hate crimes are often the result of people thinking the world needs protecting from gay people. But attacking gay people only forces them underground and into behavior that’s dangerous not only for them, but also the general public. This relationship between threatening gay people and increasing individual and public health risk is especially acute for HIV/AIDS.

If having HIV implies one is gay (a gross inaccuracy as the majority of people with HIV are not gay), and if being gay can get you beaten or killed, who in their right mind, gay or straight, is going to seek HIV testing and care? To do so, in some people’s minds, would amount to admitting you’re gay—and putting a target on your back. Ironically, gay hate crimes end up killing more than their intended prey. They can lead to illness and death among people of all sexual orientations and are counterproductive to widespread wellness in any nation.

And, they’re just plain wrong.

Homosexuality is currently illegal in Uganda (and can result in up to a 14-year jail sentence); Bahati’s proposed bill intensifies the criminalization of homosexuality by introducing the death penalty for people who have previous convictions, are HIV positive, or engage in same-sex acts with people younger than 18. The bill also includes provisions for Ugandans who engage in same-sex relations outside the country—people can be sent back to Uganda for punishment. Not that there are many safe places to go; laws against same-sex relations exist in nearly 80 countries.

Finally, the bill outlines penalties for individuals, companies, media organizations or nongovernmental organizations that support LGBT rights. (As in, if you know your neighbor’s gay and don’t say so, you can get into huge trouble yourself.) It engenders nothing short of a witch hunt.

The bill came on the heels of assertions made by American evangelical Christians at a March 2009 conference in Kamapala titled “Exposing the Truth Behind Homosexuality and the Homosexual Agenda.” They suggested that “homosexuality was a direct threat to the cohesion of American families.”

|

Rachel Maddow invited Bahati to her eponymous show on MSNBC and asked him to describe exactly how gay people threaten the American family (or people in general). He claimed that gay people engaged in tactics to make other people gay, but, when pushed, could not provide a single example, let alone proof, that this was true. He said videos intending to make children gay were circulated in schools, but no such video has surfaced.

An international backlash (in the mass media and on political and economic fronts) against Uganda resulted in a proposed revision to the bill that would replace the death penalty with life in prison. Many religious, LGBT and human rights groups spoke out against the bill and sent letters and video messages to Uganda’s leadership asking them to reconsider. Even the Roman Catholic Church stands against the bill.

In response to the outcry, James Nsaba Buturo, Uganda’s minister of ethics and integrity, said, “We now think a life sentence could be better because it gives room for offenders to be rehabilitated. Killing them might not be helpful.”

Memo to Buturo: Suppressing the rights of gay people is not helpful. It puts them in situations where they cannot necessarily protect themselves or others, which in turn endangers public health.

In response to Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Bill, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria said, “Excluding marginalized groups [from prevention and care outreach] would compromise efforts to stop the spread of AIDS in Uganda where 5.4 percent of the adult population is infected with HIV.” Elizabeth Mataka, United Nations’ special envoy on AIDS in Africa, “expressed concern with the bill as it will dissuade people from getting tested for HIV if they will be subsequently punished with the death penalty.”

And the 16,000 members of the HIV Clinicians Society of Southern Africa sent a letter to the Ugandan president stating, “Encouraging openness and combating stigma are widely recognized as key components of Uganda’s successful campaign to reduce HIV infection.”

As we go to press, the bill remains under consideration by Uganda’s parliament.

And while Uganda’s proposed law is one of the harshest in the world, its tenets are unofficially put into practice around the globe. Gay hate crimes occur all over, notably in the Caribbean but also in the United States, and the crimes range from taunts and bullying to assault and murder.

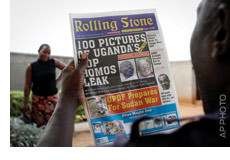

The death of David Kato, Ugandan gay rights activist, is a prime example. There is still debate over whether Kato’s death was a gay hate crime or the accidental outcome of an altercation during a robbery of his home. Given the fact that his face appeared on the cover of the Ugandan publication Rolling Stone in conjunction with an article inciting people to target and murder gay people, it’s hard to believe that his life ended coincidentally just months later.

|

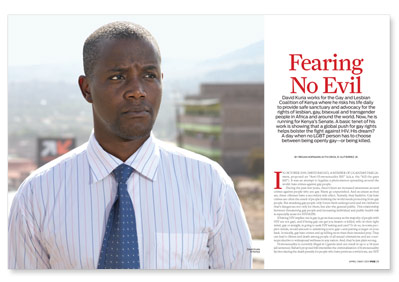

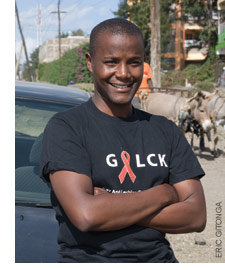

This is where David Kuria comes in. Though based in Kenya, not Uganda, Kuria is the former head of the Gay and Lesbian Coalition of Kenya (GALCK). Today, he continues to work with the group as it lobbies for human rights, access to health care and laws to protect LGBT people. He is running for the Kenyan Senate.

Kuria knows that attitudes kill just as surely as lack of clean water, food, shelter, roads, doctors and drugs. And he has dedicated his life—and risks it every day—to fight the discrimination, bigotry, hate and stigma around LGBT people in order to protect and save not only their lives, but also the lives of people around them.

He is a prime example of, thankfully, many around the world who stand up against the terrible hate that threatens the health of individual LGBT people, and, in turn, the health of the public. A soft-spoken, articulate, smart, tough, young man, Kuria is incredibly patient and benevolent when describing those who’d like to take his life. He seems deeply sad, incredibly determined and remarkably fearless when speaking about his role in the fight against gay hate crimes and legislation that would promote killing people simply because they are gay.

We spoke with Kuria in Washington, DC, about his work with GALCK and his plans to help the world overcome its fear of gay people.

Tell us about GALCK.

At GALCK, we advocate for [LGBT] human rights. We also advocate for access to health services and safe spaces. We try to change policies and laws. The center is free.

We have a drop-in center where people can just come to be who they are, to drop that other persona, drop the mask that they have created. Often people are just interested in having a chat with a fellow human being at a human level and then going home.

Of course, we have security features. Video cameras see who is coming in. If you come as a group, then the door will not open. It is relatively safe, [but] at the end of the day, the center closes down and people have to go home. [Then, they are less safe.]

Did you know David Kato, the Ugandan LGBT activist who was killed earlier this year?

Yes, I knew David Kato. We met for the first time in 2006 at an East African convening of LGBT rights activists in Kenya, then in 2007 at the World Social Forum in Nairobi.

David was an outspoken activist who did not accept any form of discrimination. It pained him personally, even when he was not the one being discriminated against.

At one point, when Ugandan activists ran to Kenya for safety and worked for a few weeks at the GALCK offices, we in Kenya still relied on David back in Uganda to speak out on our behalf. He will certainly be missed.

How has his death affected GALCK and your activism?

David’s brutal murder woke us all up to the fact that there are people out there who are ready and willing to kill on account of sexual orientation or gender identity. On any single day, we are likely to face verbal abuse and occasionally physical abuse.

We know that we may have to pay the ultimate price for our work, but it is not the kind of thing we think of until it happens to one of us. It happened to David Kato. The [LGBT] community is scared.

Even though David’s murder does scare us—knowing as we do that our own murderer could be lurking behind some corner—we feel we owe it to David to be even more vocal and energized in our work. We cannot give up. If we did, David’s death would be in vain.

Has the situation worsened for activists in Africa as a result?

The immediate reaction was an emergence of two kinds of schools of thought. The first says LGBT activists, and David Kato in particular, had it coming. Their view is that LGBT people are sinful and the wages of sin is death. They view this as the religious outcome.

Then there is the second group who, without engaging in the moral debate, are now asking whether it is acceptable to stand and watch while human rights are violated. The discussions are ongoing, and it is hard to know which group will hold sway. But for the first time, there is no automatic and universal condemnation of LGBT people.

We hope the accused, if found guilty, will be given the maximum sentence. We do not support the death sentence, not even for him. But he should spend the rest of his life behind bars. The same should happen to all the others who have cut short the lives of LGBT people in East Africa [and worldwide].

Is there a link between fighting against HIV/AIDS and fighting for LGBT rights?

When you force [LGBT] people to live double lives, one of the largest ways [of HIV transmission] is through multiple sexual partners [and unprotected sex]. There are other issues concerning HIV treatment. When you are constantly arrested and withdrawn from treatment, you can develop a drug resistant strain [of the virus].

The more people that we put at risk for HIV transmission means the more that we [as a society] are exposing ourselves to a larger epidemic. The transmission rates increase exponentially, at a rate that [means] we cannot afford to buy treatment [for all who need it].

What is it like being LGBT in Kenya?

|

It is difficult to be safe. If someone identifies you as [LGBT], you’re subject to homophobic attacks or bullying. People believe that it is you that has a problem, not the people who are doing the beating.

I am out on TV and daytime news and in the newspapers. What that has meant is that I don’t have a social life. You do not know what will happen to you [if you go out to a club or a bar, for example].

It’s unfair to be forced to live two lives, to lead a false identity [as a straight person] that denies the [LGBT] identity. When you are denied a job, denied access to health services, when you are habitually arrested, when you live with fear, it’s really dehumanizing.

In Kenya, it seems that men who lead double lives do so because they do not believe they have a choice—it is either marry a woman or risk being killed. Is it possible for these men to have honest conversations with their wives about their situations? [No.]

There would be value in saying [to your wife], “You are my friend, we need to work together.” The thing is, what if your partner told on you? There is a risk [of your secret being revealed].

Men are not able to tell their female partners [they are gay or bisexual] because you need your story to be believable. [If the woman knows, the illusion may be broken.] I tell people, “If you see it’s in your interest [to be] out to them, then you should do it.”

If you are in such a relationship, your wife is obviously not going to be happy in it. She may seek comfort somewhere else, so she also puts you at risk [for HIV]. It is in your interest that you are honest with your partner, but of course it is easier said than done. The biggest problem within these kinds of marriages is getting people to use condoms.

What made you become an activist?

In 2000, [LGBT] people were making gains [in Kenya] and [I believed we could] push hard enough to [make progress].

I also was working at a Roman Catholic institution where I lost my job as a teacher [because of LGBT discrimination]. The loss of my job was a catalyst [for the work I do now].

I want to be in a position where I can have greater influence. Advocacy is important, and I will continue that advocacy. But we also need to be at the table where the policies and the laws are made.

Would you encourage others to become activists?

This is a job that needs to be done right now. There isn’t a lot of support, but increasingly there is recognition that neglecting one side of society will not conquer HIV/AIDS.

There are benefits to the job. Seeing people’s health improve, seeing people come out and accept who they are and being happy about themselves is exceptionally rewarding. I call on people to join us.

Human rights and gay rights are not distinguishable. If you find yourself creating a distinction, then you do need to question your value of human rights.

4 Comments

4 Comments