|

| Cecilia Aldarondo |

My memories of Miguel’s funeral in Puerto Rico are much more vivid. It was my first brush with death, and I found it very frightening to be surrounded by grieving adults. Even my fat macho grandpa, always so stoic, had tears running down his cheeks. However, what I don’t remember, because I didn’t know it at the time, was that my uncle’s lover Robert was sitting in the back row of the church as my family sat mourning up front. I didn’t know it because no one in my family mentioned his presence.

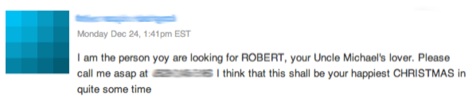

I only found out years later, when I moved to New York and went looking for Robert. After two years of false leads and dead ends, I’d pretty much given Robert up for dead. Until Christmas Eve 2012, when a message showed up in my inbox. It was only a couple of lines long.

|

It seemed too good to be true. For days I was convinced it was some kind of scam. But then I called the number. And the voice on the other end was very real, and very raw.

But it didn’t belong to Robert, not exactly. The voice told me, ‘When Miguel died, Robert died also.’ Instead, he asked me to call him ‘Father Aquin;’ after Miguel died, he’d found solace in the Catholic Church, and had been reborn as a Franciscan friar.

For the past several years I’ve been making a documentary, Memories of a Penitent Heart, which explores the conflicts that lingered after Miguel’s death. See, as I was growing up people in the family whispered about certain things. About how Miguel, instead of dying of ‘cancer’ as his mother Carmen told everyone, probably had AIDS. About how he’d been living with some guy, Robert, for a long time before he died. About how Carmen had begged Miguel to see a priest as he was dying so that he could wash away the sins of his homosexuality, before it was too late. But as much as people whispered, what they did not say was what truly interested me.

Watch this video to learn more:

When I flew out to California to meet Aquin for the first time, he handed me a cardboard box that he’d kept in a closet for 25 years. The box contained all the traces of his and Miguel’s relationship—snapshots, love letters, hospital documents, Miguel’s unfinished plays. It took a total of nine hours to go through the box, as he told me all about his life with Miguel. When we were done, he handed it to me: ‘Take it,’ he said. ‘I don’t want it anymore.’

It’s hard to describe the responsibility I feel in receiving this box. In my mind, the box contains an untold history, the forgotten undercurrent of Miguel’s life. Take the obituary clipping that was in the box as an example. It names the surviving next of kin—parents, sister, brother—but makes no mention of the man who was Miguel’s companion for over a decade.

These documents have challenged my family’s version of events, and offered a fuller texture to Miguel’s life as a gay man. It isn’t just Miguel’s history that has emerged in the telling, or even Aquin’s—it is the history of my uncle’s closest friends, a tight-knit community of people who’d witnessed him in sickness and in health, and who’d never really gotten the chance to grieve him as Miguel’s biological family had. I have also come to see my uncle, not as a repentant struck through with the fear of God’s wrath, but as an anguished son and brother who felt caught between love for his family and a burning resentment at his lack of legitimacy among them.

A lot of straight people have reacted to this documentary as though it isn’t a film for or about them. But isn’t that precisely what my uncle was kicking and screaming about? The fact that no one in his family really thought that his being gay had anything to do with them? The fact that the best he could hope for from them was a neutral stance? How many other gay men died feeling that their families didn’t really know them? How many partners were locked out of their rightful homes, excluded from funeral arrangements, or left to grieve alone? How many wished they’d had an ally, a vocal advocate when the conflicts began? And how many families of choice broke apart after the deaths of their friends and lovers, in part because they lacked the legitimacy of official mourning?

It’s a tricky thing, asking these questions. Some people have told me it’s none of my business, or that I should have waited until all the key parties were dead to go snooping around. Others have said the opposite—that it’s too late, and I should leave the past alone. At other times I’ve been greeted with rightful suspicion by long-time AIDS veterans because I ‘wasn’t there’ to go through it. But as I see it, one of the factors that made AIDS turn from a preventable public health concern into a raging crisis in the first place was that straight people didn’t care until it was too late. I believe that the AIDS crisis is one of the great horrors of the 20th century, and that we as a nation have yet to fully comprehend our complicity, not only in the deaths of so many, but in the lack of proper mourning afforded to friends and lovers. If Aquin had 25 years of pent-up mourning inside of him, I can only imagine how many others might still be carrying the same burden. And while it may be too late to give my uncle the death he deserved, I can only hope that I can do my part to remember his life in all its complexity.

Cecilia Aldarondo is a filmmaker based in New York. To support the completion of Memories of a Penitent Heart, click here.

4 Comments

4 Comments