|

| Samuel Freedman |

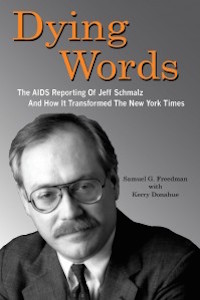

The following, written by journalist and author Samuel G. Freedman, is an excerpt from the foreword of Dying Words: The AIDS Reporting of Jeff Schmalz And How It Transformed The New York Times.

Jeff died on November 6, 1993, at the age of 39. On a strangely glistening night several weeks later, I went to his favorite restaurant, Chanterelle, for a private memorial service that somehow, in an unforced way, became a festive celebration of his life. I knew from Jeff that his sister Wendy, his only sibling, was a literary agent. I introduced myself to her that night, and I told her how honored I was to have been invited. I asked her how she had chosen the guests. “This was supposed to be Jeff’s 40th birthday party,” she explained. “He’d made up the list.”

Death was Jeff’s final lesson to me. Just as he was the first openly gay man I knew, he was the first person I knew to die of AIDS. In the years since then, his absence has harrowed me. I could not separate the upward arc of my writing career from the ways Jeff had elevated my abilities and negotiated my way through the labyrinth of Times newsroom politics, which had ruined people far more talented than me. For lack of a better term, I felt survivor guilt. And beyond it, I grieved that as the years passed, fewer people would remember who Jeff Schmalz was and what tremendous work he had done.

|

Indeed, one evening nearly 20 years after Jeff’s death, my fiancé and I were having dinner with another couple — she a screenwriter, he a former magazine journalist now working on a cable series about journalism. The conversation turned to New York State’s recent legalization of same-sex marriage, a stance vociferously endorsed by The New York Times. I mentioned how remarkable it was to me, having lived through such a homophobic period on the paper, to see The Times become a champion of gay rights. Then I found myself talking about Jeff and his AIDS articles, fully expecting that my friends would be familiar with him and them. But they drew a blank.

That blank, of course, made sad sense. Jeff had been dead for a generation. Newspaper writing is evanescent, as perishable as the paper it is printed upon. Still, I could not believe that people who would know the names and work of Randy Shilts, Larry Kramer, Tony Kushner, Craig Lucas, Michelangelo Signorile, Andrew Sullivan — those artists and journalists who bore witness to the AIDS plague — could not know of Jeff Schmalz. It felt like a moral duty for me to do something to rescue Jeff from obscurity.

Those friends at dinner suggested a film, but I am no filmmaker. They suggested writing a biography, but I believed Jeff had left his own written record. As months passed, what came to me was the sound of voices — the voices of those who had known and worked with Jeff, the voices of those whom he had interviewed, the voice of Jeff himself. The story of Jeff Schmalz, it seemed to me, wanted to be a radio documentary. And in book form it wanted to be an oral history.

I went to see Wendy Schmalz Wilde, to ask for her blessing. She gave me that, and she gave me more: a set of micro-cassettes on which Jeff had recorded his AIDS interviews. I also went to see Arthur Sulzberger, Jr., Jeff’s friend and the publisher of The New York Times. I sought both institutional and personal support — not because the documentary and oral history will be authorized, sanitized accounts of Jeff’s years at The Times, but precisely because the newspaper must be shown with its flaws in how it reported on gay issues and how it treated its own gay staff members.

Although I continue to maintain a formal association with The New York Times, writing a monthly column on religion, the content of this book and the companion radio documentary were produced by me and my collaborator, Kerry Donahue, with complete editorial independence.

We began with a clear, linear goal: to recount Jeff Schmalz’s life and work in his years on The Times. As we proceeded, though, it soon grew evident that Jeff’s story unfolded into larger stories: what it meant to grow up gay amid anti-gay bigotry; how wrenching it was to come out, for fear of being scorned by friends and family and ostracized or fired by employers; the blind spot in the conscience of the nation’s most powerful and respected newspaper; the sheer terror and rampant death experienced by people with HIV or AIDS in the years before drug cocktails made them endurable diseases.

There can be no gainsaying the bleakness of disease, death, self-denial, and bigotry. And yet, finally, Jeff’s experience tells us something essential about the positive changes in American society, including The New York Times, in the acceptance of its LGBT citizens over the past generation. Jeff Schmalz did not live to see those changes, but his life and work helped to make them possible.

Comments

Comments