In much of the United States, spring is well underway. Though nature’s green glory is a welcome change, springtime can also bring misery to those of us susceptible to allergies. Those beautiful budding trees and blossoming flowers harbor a menace—pollen—that can condemn many of us to weeks of sneezing, runny noses, red eyes and, if we’re not vigilant, sinus infections.

Untreated allergies are one of the leading causes of sinus infections, or sinusitis. Though sinusitis is rarely a life-and-death matter—thanks to potent antiretrovirals that keep immune systems healthy and harmful bacteria from spreading—it does diminish the quality of life for large numbers of people.

Experts disagree about whether allergies and sinusitis are more common, have a worse course or need to be treated differently in people living with HIV. They all agree, however, that no one—HIV positive or negative—should suffer needlessly. Douglas Ward, MD, a longtime HIV treater from the Dupont Circle Physicians Group in Washington, DC, says, “[Sinusitis] is the No. 2 diagnosis [in my practice].”

For those with minor or brief seasonal allergies, a little information and over-the-counter (OTC) self-care will probably be sufficient. For those with more severe problems—such as fever, sinus pain or a bad cough—or those with respiratory diseases like asthma or chronic bronchitis, a health care provider’s care and guidance could mean the difference between enduring a short stretch of symptoms and never-ending days of head-splitting sinus pain, difficulty breathing and major discomfort. Ward says, “If you’re coughing up green phlegm, you’ve got an infection. Don’t think, ‘Oh, it’s just allergies.’ Get it looked at and treated.”

Sinus science

Our nasal sinuses are pockets of air-filled mucus membranes that are connected to the nose by small passages called ostia. Though scientists argue about their primary purpose, these hollow cavities protect our eyes and the roots of our teeth from rapid temperature fluctuations and help cushion our brains if suffering a blow to the face.

| |

| The air-filled nasal sinuses can become infected when clogged with mucus from allergies, leading to facial pain and pressure, nasal blockage, greenish-yellow discharge and sometimes fever. |

But the ostia are easily clogged by mucus in our noses and the swelling of the mucus membranes caused by allergies or cold and flu viruses. According to Rona Vail, MD, an HIV specialist at Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in New York City, when the ostia become clogged, “The mucus just sits there without the ability to drain and then the bacteria, or fungus or [viruses trapped in the sinuses] multiply and end up causing a problem.”

Vail says that there’s some controversy among primary care physicians about whether sinusitis is overtreated, particularly with antibiotics, and so they’ve developed criteria to properly diagnose it. She says, “The kind of symptoms that [doctors look for] are facial pain and pressure, nasal blockage…and also nasal discharge that is greenish-yellowish, loss of smell sometimes, and fever…. Other things that people [experience] are headaches, bad breath, pain in the teeth, sometimes pain in the ears.”

Before the era of combination antiretroviral (ARV) treatment began in 1996, sinusitis was a serious problem. Chronic sinusitis, lasting 12 weeks or more, or recurrent sinusitis, was all too common. Though ARV therapy preserves many people’s immune systems, protecting them from the most severe and lingering forms of sinusitis, expert opinion is mixed about whether sinusitis remains worse or more common among people living with HIV.

Vail and Ward say that sinusitis is about equally common in their HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. Antonio Urbina, MD, medical director of HIV/AIDS education and training at St. Vincent Catholic Medical Center in New York City, on the other hand says that the incidence of sinusitis “is still higher [in people with HIV] than persons who are HIV negative, but less now in the era of [ARV therapy].”

Whether or not sinusitis is more common in people with HIV, all support treating its underlying causes. To guard against cold and influenza virus infections, experts recommend that people get their flu shot each year and wash their hands thoroughly many times throughout the day. For allergies, Vail and Urbina recommend a combination approach that may include steroid-based nasal inhalants and oral antihistamines and decongestants. The steroids and the antihistamines calm down the immune system’s response to whatever you may be allergic to. The decongestants simply block the production of mucus.

People with asthma or other obstructive respiratory problems, such as emphysema or chronic bronchitis, should also monitor their allergy symptoms with the help of a health care provider, as seasonal allergies can sometimes trigger serious flare-ups of these diseases.

Why call my MD when there’s OTC?

It’s hard to say whether people living with HIV are better than their HIV-negative peers about turning to a health care provider when allergies or sinus infections arise. Some may be concerned that their allergy symptoms are HIV med side effects or signs of an AIDS-defining opportunistic infection, prompting a call to their doctors. Others, however, may feel silly calling their doctor about sniffles, sneezes and wheezes while undergoing care for a potentially life-threatening disease like HIV.

One reason to consult a health care professional about allergies is to pick and choose OTC medications wisely.

Another reason to seek professional guidance is when allergies may have possibly crossed the line into sinusitis. Though Urbina says that many sources of sinus infections are viral, bacteria can also cause them, and prescription antibiotics are often used to treat bacterial sinus infections. Catching infections early often results in a faster recovery and less time feeling ill. Vail cautions, however, that “antibiotics are great for the initial relief of the infection and the pain, but they’re not enough.”

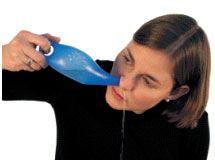

Vail is an advocate of a do-it-yourself method that’s low cost—saline nasal irrigation.She admits that “people often don’t want to do it, because it gets kind of messy.

| |

| Nasal irrigation, with a properly mixed warm saline solution, doesn’t burn. In a Neti Pot (pictured), or rubber ear syringe, mix ½ teaspoon kosher salt with 8 ounces of warm water (first timers may wish to reduce salt and water amounts by half). Lean over the sink—or stand in the shower—and rotate your head to the side so that one nostril is directly above the other, with your forehead remaining level with the chin, or slightly higher. Gently insert the Neti Pot spout into the upper nostril, forming a comfortable seal. Keep your mouth open and raise the handle of the Neti Pot, so that the solution enters the upper nostril and drains out through the lower. Repeat with another 4- to 8-ounce saline mix in the other nostril. |

Other OTC options include nasal sprays, although Vail warns against the use of brands that contain oxymetazoline hydrochloride (found in Afrin, Zicam, etc.). She uses the word addiction to describe some people’s attachment to these nasal sprays, explaining, “I know why people get hooked on Afrin, because they immediately feel better. But in the long run it causes rebound inflammation and swelling and the problem just gets worse and worse.”

Antihistamines, which include over-the-counter drugs like Benadryl (diphenhydramine), Claritin (loratadine) and most recently Zyrtec (cetirizine), may be used regularly throughout a bout with allergies. About decongestants, which include pseudoephedrine (Contac Non-Drowsy, Sudafed, etc.) and phenylephrine (Sudafed PE), Vail says, “[They] are fine for short-term use, just for symptom relief.”

Prescription options, such as inhaled corticosteroids like Nasarel (flunisolide) and Nasonex (mometasone), can be particularly effective if people start using them at the first sign of symptoms, as the drugs can take a while to start working. People with HIV should beware, however, of potential interactions between many HIV drugs and the corticosteroid fluticasone (found in Advair, Flovent or Flonase). Norvir (ritonavir), especially, can substantially raise blood levels of fluticasone, leading to an increased risk of Cushing’s syndrome, an endocrine disorder that can result in obesity, water retention and puffiness, diabetes, high blood pressure, thin skin, aches and pains, and mood swings.

Immunotherapy: Hope for long-term allergy relief

Another allergy remedy that can work when allergies are persistent and don’t respond well to other treatments is allergy desensitization immunotherapy, also known as allergy shots. Desensitization involves injecting a person with small but increasing amounts of the substance they are allergic to, known as an allergen, so that the immune system develops a tolerance for that specific allergen. When it works well, some people are able to do away with a daily regimen of pills and inhalers, and even when a person can’t stop allergy meds altogether, they often find they have to take them less often.

When it comes to desensitization for people living with HIV, official recommendations and actual practice are not necessarily in agreement. According to Roger Emert, MD, a specialist in allergies and immunology from the Weill Cornell Medical School of New York Presbyterian Hospital, “The recommendations from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology are that if someone is HIV positive they should not get allergy desensitization immunotherapy.”

Recommendations like these were often issued when having HIV almost invariably meant having AIDS and a compromised immune system. Aside from the fact that desensitization probably wouldn’t work as well in people with CD4 cells in the single digits, experts feared it could also do harm. Times have changed, however, and now plenty of people have good CD4 counts and undetectable virus. Emert is willing to buck the official recommendations for these individuals. He says, “I have done [desensitization] with HIV-positive patients successfully without any problems. If your HIV viral load is undetectable, there’s no reason that I know of that it would adversely affect the immune system.”

Still, people wishing to undergo allergy desensitization should probably ensure that their primary HIV care provider work closely with the allergy specialist to guard against any problems.

If treated early and appropriately, allergies can be reduced to a mere nuisance. If left untreated or mistreated, however, minor symptoms can literally turn into a major headache. And while everyone else is outside enjoying the sunny days of springtime, you may find yourself in bed with sinusitis, too sick to smell the flowers.

Image sources: (sinuses) A.D.A.M., Inc., (Neti Pot) himalayainstitute.org

10 Comments

10 Comments