Sir Elton John admits in his latest book, Love Is the Cure, that he could have done more to fight AIDS in the beginning of the epidemic. While he did what he could to help friends and loved ones as they succumbed to the disease, at the time, the legendary musician, songwriter and performer was battling his own demons. For years, John struggled with drugs and alcohol. It was the AIDS-related death of his young friend Ryan White in 1990 that inspired John not only to get sober but also to fully engage in the battle against HIV/AIDS.

Sir Elton John admits in his latest book, Love Is the Cure, that he could have done more to fight AIDS in the beginning of the epidemic. While he did what he could to help friends and loved ones as they succumbed to the disease, at the time, the legendary musician, songwriter and performer was battling his own demons. For years, John struggled with drugs and alcohol. It was the AIDS-related death of his young friend Ryan White in 1990 that inspired John not only to get sober but also to fully engage in the battle against HIV/AIDS.The Elton John AIDS Foundation (EJAF) was created in 1992. Its mission is to address the importance of eliminating stigma and discrimination and allowing HIV-positive people to live with dignity. Early on, John recognized the need for EJAF to fund the programs and services that no one else would touch, such as needle exchange programs or outreach to sex workers. To date, EJAF has raised more than $275 million in support of worthy projects around the world.

This July, John gave the keynote address at the XIX International AIDS Conference in Washington, DC. The message of his speech was the same as the message in his book: Love is what’s needed to truly end the AIDS epidemic. We now have the tools to stop HIV in its tracks, but without compassion and understanding for those living with the virus, we will never defeat it.

In the following excerpt from his book, John describes an unexpected meeting with a U.S. president and outlines what governments around the world can—and should—do to help end the epidemic.

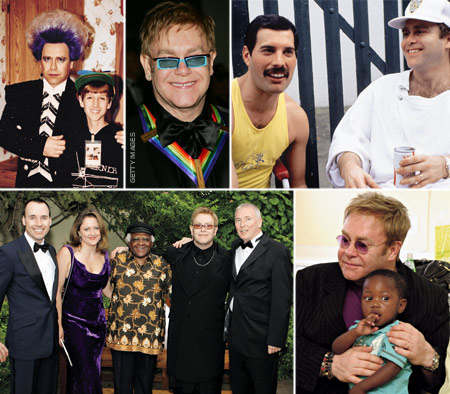

I was very surprised and flattered to be selected to receive the prestigious Kennedy Center Honors [in 2004], which are given to only a few entertainers each year in recognition of their cultural contributions to American life. It is a big deal—I knew that much. But to be quite honest, at the time [my partner] David and I were quite torn about whether I should accept the honor. The award itself is presented by the sitting president of United States, and I was no great fan of George W. Bush, apart from his position on AIDS. More than that, I was morally opposed to many of his policies, and I took personal offense to many of his pronouncements. Ultimately, however, David and I came to realize that the Kennedy Center Honors were bestowed not by a president but by a nation, and my love and respect for America were much more important than any political statement I could make by refusing to accept an award from George W. Bush.

David and I flew to Washington, and the first order of business was a formal dinner at the U.S. State Department, during which each Kennedy Center honoree is presented with a medallion. After a few kind words, Colin Powell, the secretary of state, hung the medallion around my neck. When I got back to my seat, David and I chuckled to ourselves, because as it turns out the medallion itself is several metal bars with a big, rainbow-colored ribbon that looks identical to the Gay Pride flag. And I was very proud to wear it, of course.

The next day, we went to the White House for the formal citation reading ceremony. As we walked up those grand steps, it wasn’t excitement we felt but apprehension. We were entering the lion’s den, we thought. David and I had no idea how we would be treated or what the experience would be like for a same-sex couple visiting a Republican White House that seemed openly hostile to gays. But we were immediately put at ease by an Air Force pilot who was assigned to be our White House escort. You’ve never seen a more handsome man in your life, especially in that uniform! And what’s more, I instantly knew he was gay. These were the days when you weren’t supposed to “ask” and they weren’t supposed to “tell.” But, of course, I couldn’t help myself. “You’re gay, aren’t you?” I said. He smiled and nodded. To this day, our Air Force escort is a great friend of ours.

The award presentation was in one of the beautifully ornate receiving rooms at the White House. President Bush read citations for each honoree. When it came to my turn, the president began to list some of my hit songs over the years, including “Crocodile Rock,” “Daniel” and—in one of the president’s legendary verbal miscues—“Bernie and the Jets.” Just then, First Lady Laura Bush interrupted the president and yelled out, “It’s Bennie and the Jets!”

The president and everyone in the audience had quite a laugh. That is, except Dick Cheney. When President Bush finished reading my citation and the audience applauded, David and I were stunned to see the VP sitting there with his arms folded and a scowl on his face. It may have been that he still had bad feelings about my quote to a British publication a few weeks prior, that “Bush and this administration are the worst thing that has ever happened to America.” I suppose I can’t blame him for being unhappy with me about that!

That evening, it was a wonderful gala concert at the Kennedy Center Opera House—a very moving event during which my friends Billy Joel and Kid Rock serenaded me with my own songs. David and I sat in the special box with my fellow awardees: Warren Beatty, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, Joan Sutherland, and John Williams. At intermission, our group filed into the hospitality area behind the box. Our seats were next to the president’s, and little did I realize that our boxes shared this hospitality room in common. Suddenly I was standing next to a bunch you wouldn’t think of as my usual concertgoers: Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, Condoleezza Rice, Colin Powell and, yes, President Bush.

It was a surprising moment indeed, but the real surprise would come when the president and I had a chance to speak. I remember having the greatest conversation with him. He was warm, charming and very complimentary, not only about my music but also about the work of my foundation. He knew all about what we were doing, and he was endlessly knowledgeable about HIV/AIDS as well.

President Bush and I discussed the epidemic for quite a while, and he asked if there was anything he could do to help EJAF. I thanked him for his offer, but I said that his commitment to PEPFAR [the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief] had already done a world of good, and I commended him for all he was doing to fight AIDS abroad. At that point, I felt compelled to ask if there was anything I could do to help him. “Yeah,” he said, with a look of dead seriousness on his face. “Tell the French they need to give more money.”

You see, at that point, France had not yet made a significant commitment to fighting the global AIDS epidemic, and President Bush was truly angry about it. The French government has since spearheaded the creation of a wonderful multigovernment program called UNITAID, which funds the purchase of HIV/AIDS medications and other global health needs for poor countries through a small tax on the purchase of airline tickets. But back in 2004, President Bush was lobbying for them to do more. This wasn’t a political issue to him, or some side project. He genuinely cared about people around the world who were dying of AIDS.

I’ll never forget our meeting that night. President Bush and I haven’t seen each other or talked since, and like many people, I deeply regret much of what he did in office, especially the wars he waged in Iraq and Afghanistan. But my encounter with George W. Bush reminded me not to rush to judgment about people, especially when it comes to fighting AIDS. More than anything, we need allies in this fight, not enemies.

That was one important lesson learned from the implementation of PEPFAR. The other was one I grew to understand, not just from watching PEPFAR’s creation but from my own experience testifying before Congress, and from years of EJAF’s work around the world: There is no institution on earth, not one, that is as capable of making sweeping changes as government.

Governments have the power to entirely remake the societies they govern. They have the power to battle, to wage war, not just on other nations but on poverty, on injustice, on epidemics. They have the resources and influence to change the future, and the choice of whether or not to do so. And with a disease such as AIDS in particular, they have a unique ability to fund treatment and care, education and prevention. They can ensure that all their citizens have access to lifesaving medicine. Governments are, without question, the single biggest factor in determining whether AIDS will be a death sentence for their people, or whether their HIV-positive citizens will survive.

Governments of the world are more than just resources for funding. They also have an unmatched ability, without spending a penny, to fight the terrible torment of stigma. Government, after all, has the ultimate megaphone. All it takes is a president or prime minister to say, “It doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from, you deserve the dignity of having your life valued as much as the rest of us.” All it takes is for lawmakers to speak up for their marginalized constituents. All it takes is leaders to proclaim that they will not let a disease ravage people living in their communities. In an age of ubiquitous communications, these statements alone can have a tremendous impact.

It is all too easy for political leaders to think about AIDS only in the abstract. It is all too easy for them to forget that there are real people counting on them for help, people who deserve the same chance to live a long life as anyone else.

In the end, the only way we will end AIDS is with a commitment to do so not just from one government but from all governments. A commitment from governors and presidents. From premiers and prime ministers. From Asia to Africa to Europe. Governments can be the greatest force in the fight to rid the world of AIDS. But only if they so choose.

This is an excerpt from Love Is the Cure by Elton John. Copyright © 2012 by Elton John. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

5 Comments

5 Comments