Each year for the past quarter century, thousands of the world’s top HIV scientists have gathered at the United States–based Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) to share important scientific findings with their peers. This year’s conference, held in Boston March 4 to 7, was notably lacking in blockbuster presentations but was nevertheless rich with science that will fuel efforts to better control the global HIV epidemic as well as the overlapping hepatitis C virus (HCV) epidemic.

To follow is a rundown of studies presented at the conference. To read about any of them in greater detail, click the hyperlinks. You can also access a complete newsfeed of dozens of articles about CROI by clicking here or the #CROI2018 hashtag at the bottom of the article.

BostonIstock

Treatment:

Good news out of San Francisco: The city reported that it has made considerable progress in its aggressive effort to treat people with HIV immediately after diagnosis. Recently chosen as the site of the International AIDS Conference in July 2020 (amid some controversy), the city has narrowed the gap between diagnosis and treatment start to just six days as of 2016.

San Francisco is fast gaining impressive control of its epidemic.Source: San Francisco HIV Epidemiology Annual Report, 2016.

Gilead Sciences’ recently approved Biktarvy (bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide) is considered an advancement in HIV treatment because the single-tablet antiretroviral (ARV) regimen is based on the integrase inhibitor bictegravir, a drug that is highly effective, has a high barrier to resistance and includes the new, safer version of tenofovir. A new study presented at CROI showed that switching from Triumeq (dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine) to Biktarvy is safe and effective. However, the study didn’t show that Biktarvy provided any significant benefits over the former during the 48-week study period.

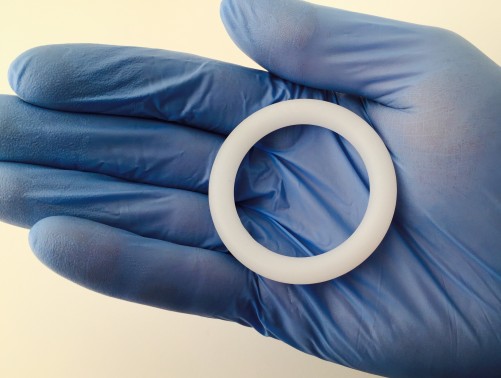

Researchers raised new concerns about Sustiva (efavirenz), an older ARV that a new study indicated may compromise birth control that’s delivered through a vaginal ring. Sustiva is included in Atripla (efavirenz/tenofovir/emtricitabine) and has fallen out of favor in the United States in recent years because it is associated with many troubling side effects, including nightmares.

Cure:

At the 2013 CROI, a presentation about the so-called Mississippi Baby spurred worldwide excitement and fanfare. It seemed at the time that an atypically aggressive regimen of ARVs given to the infant immediately after she was born to an HIV-positive mother had possibly led to a functional cure of the virus. But the child’s HIV ultimately rebounded, raising many important questions about how early treatment may limit the size of the viral reservoir but not eliminate it.

A new study presented at this year’s conference found that starting HIV-positive infants on ARVs very early is indeed associated with the establishment of a smaller reservoir in these infants. The researchers’ findings also indicated that leaving a gap between the prophylactic use of ARVs among newborns and the beginning of a traditional treatment regimen (once tests have confirmed that the infants have contracted the virus) is linked to the establishment of a larger reservoir among such infants.

Another study showed promise in the effort to prompt an individual’s immune system to control HIV over extended periods without the need for daily ARVs. Researchers studied primates infected with a simian version of the virus, treating them with standard ARVs and adding a period of treatment with the broadly neutralizing antibody PGT121 and the immune-stimulating agent GS-9620. After all treatments were stopped, the animals that received both of the additional treatments, compared with those who received a pair of placebo treatments instead, experienced about a 100-day delay in their viral rebound. Encouragingly, the animals that received the extra treatments saw their virus plateau at a viral load below 400.

PrEP:

The biggest conference news in the field of so-called biomedical prevention of HIV—using antiretrovirals (ARVs) among HIV-negative individuals to prevent acquisition of the virus—came from a pair of studies that have followed up on previously announced research about the ARV-infused vaginal ring. The African women in these two trials, who had participated in the previous placebo-controlled vaginal ring trials and now knew for sure they were getting the drug-containing ring, appeared to use the ring quite well; as a result, they contracted HIV at half the rate that they would have had they not received the ring, according to mathematical modeling.

Courtesy of NIAID

Despite the fact that PrEP has been approved in the United States for nearly six years now, researchers in this country have not been able to provide a robust analysis indicating that Truvada significantly drives down HIV rates on a population level. (AIDS Healthcare Foundation president and prominent PrEP critic Michael Weinstein has long maintained that Truvada would fail on such a grand measure of effectiveness.) However, signs have begun to indicate that such a population-level effect may be occurring in London, where PrEP has recently surged in popularity while the HIV rate has nose-dived.

Finally, Australia has stepped up to the plate, showing that after the state of New South Wales rapidly expanded access to PrEP among thousands of men who have sex with men, the state’s overall diagnosis rate of recently contracted HIV among MSM dropped by an incredible one third in only about two years.

Looking for future forms of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), scientists conducted a study in monkeys that showed that a new class of ARV was so effective at a low dose that humans could possibly take just 0.25 milligrams of the drug MK-8591 once a week and still achieve good protection against HIV. By comparison, Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine) contains a cumulative 500 mg of ARV medications.

As PrEP has rolled out across the United States—Gilead Sciences estimates that more than 150,000 people are currently taking it—it has become increasingly apparent that uptake of Truvada as prevention is quite uneven. A collection of studies presented at CROI sought to more clearly identify various disparities in the use of PrEP.

After revising their breakdown of the approximately 1.14 million U.S. residents they estimate would make good PrEP candidates, investigators at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that Truvada’s use as prevention was woefully low among Blacks and Latinos.

Source: CDC

This graph concerns all people who are indicated for PrEP use, not just one subgroup, such as MSM.Source: CDC

Meanwhile, the health metrics site AIDSVu released its first state-by-state map detailing differences in PrEP-use rates across the country. Using the same data source, an academic research team went a step further and compared the HIV rate in certain demographics to the PrEP-use rate among each demographic to arrive at a so-called PrEP-to-need ratio. The color-coded U.S. map these researchers developed vividly illustrated just how much PrEP is failing to launch in the Deep South.

AIDSVu.org

As in the past two editions of CROI, reseachers reported this year that an individual contracted HIV while apparently adhering well to the daily Truvada regimen. (This is known as a case of “PrEP failure” or a “breakthrough” infection while on PrEP.) The precise details of this new case, unfortunately, will likely remain hazy because the gay man in question didn’t have the proper tests done in time to determine whether he contracted a strain of HIV that was resistant to both drugs in Truvada or whether his virus developed such resistance during the month or so he spent on PrEP after contracting the virus.

On a related topic, a team of researchers in Seattle sought to determine how much virus in the HIV population is both transmissible and resistant to the two drugs in Truvada. After analyzing a large pool of local data, they concluded that such HIV is rare.

Comorbidities:

Comorbidities is the technical word clinicians and researchers use for “additional health problems” among individuals with an existing health problem. In people with HIV, for example, major comorbidities include liver and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Regarding CVD, researchers identified that switching from taking Ziagen (abacavir) to an ARV regimen without that drug was associated with healthier platelets. This finding may help explain why Ziagen, which is included in Trizivir (abacavir/zidovudine/lamivudine), Triumeq (dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine) and Epzicom (abacavir/lamivudine), has a reversible association with cardiovascular disease.

Ziagen

One study identified that people with HIV who also have kidney disease have a high risk of multiple serious health conditions as well as an elevated risk of death. Consequently, the study authors advocated close monitoring of such individuals in an effort to prevent or manage such health problems.

HIV is also associated with the progression of coronary plaque among men, according to one study. The investigators who reached this finding found that men with an unsuppressed viral load have a higher risk of the progression of lipid-rich low attenuation plaque than those with undetectable HIV, although this difference was not statistically significant, meaning it could have been driven by chance.

Another study indicated that the use of statins, which are traditionally prescribed to lower cholesterol and the risk of CVD, might mitigate cancer rates among people with HIV.

A massive ongoing trial called REPRIVE that is giving statins to people with HIV who wouldn’t otherwise be considered candidates for such medications aims to identify how the drug class may benefit this population. At least in theory, statins may lower the risk of comorbidities in people with HIV by reducing the kind of chronic inflammation with which even well-treated virus is associated. Results from this very important study are slated to come in 2021. (To learn more about REPRIEVE and to get information about joining if you’re interested, click here.)

Africa:

Recent major HIV science conferences have reported some astounding news about HIV rates plummeting as treatment rates have soared in certain hard-hit sub-Saharan African nations. CROI attendees learned that the HIV population in Lesotho had recently achieved a 61 percent rate of viral suppression. An estimated 77 percent of those living with the virus in this land-locked nation are diagnosed, 90 percent of that group is on ARVs and 88 percent of that group has an undetectable viral load. (The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, known as UNAIDS, has called on nations to get all three of those figures to 90 percent by 2020.)

In Uganda, an analysis of a fishing community in the Rakai district provided some of the first solid evidence of the population-level efficacy of a combination approach to HIV prevention. As the rates of HIV treatment and voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) each rose, this district saw its HIV diagnosis rate cut in half in just a few years. (VMMC reduces the risk of female-to-male HIV transmission by about 60 percent.)

One study conducted in African women found that their risk of contracting HIV rises during late pregnancy and the postpartum period of about six months following birth. Because the researchers controlled for various behavioral factors in their analysis, they believe that this shift in risk may have been driven at least in part by biological changes.

Incarceration:

A research team has identified a highly effective way to help incarcerated people who have HIV and a substance use disorder succeed on their ARV treatment after their release. In a recent study, monthly injections of the long-acting drug naltrexone, which is approved to treat both opioid and alcohol use disorders, was associated with a nearly fivefold greater likelihood that study participants would have an undetectable viral load six months after release from prison or jail.

Transmission:

A genetic analysis conducted on samples of HIV taken from individuals in Los Angeles county revealed some of the nuances of the sexual patterns of transgender women. Based on the genetic similarity between individuals’ virus, researchers determined that a significant proportion of the local trans women had as sex partners cisgender men who may identify as heterosexual, as well as other trans women.

A similar study that came out of the CDC used genetic analyses to identify clusters of individuals across the country among whom HIV is apparently transmitting rapidly. These clusters disproportionately included young MSM, in particular Latinos. This finding is quite telling because young Latino MSM in particular do not appear to be benefiting from the recent overall trend of falling HIV rates among various demographic subgroups.

Hepatitis C:

Sexually transmitted hep C among HIV-positive MSM in Western nations is a growing epidemic. HIV-negative MSM are also at risk but apparently to a lesser extent. Seeking to understand why hep C seems to transmit more readily through anal sex among those living with HIV, researchers studied skin immune cells called Langerhans cells drawn from the mucosal lining of the rectum of HIV-positive men. They found that HIV prompts key changes to these cells that facilitate the transmission of HCV.

According to a European study, only about one in ten people who have HIV will clear HCV spontaneously during the acute, or very early, phase of infection and thus not need treatment to get rid of the virus. As a result, the authors of this study advocated for broadening hep C treatment guidelines in wealthier nations to push for treatment of the virus during its acute phase among HIV-positive individuals.

Lastly, a Swiss program to systematically test and treat hep C among a large cohort of HIV-positive MSM showed great success in driving down the transmission rate of HCV in this population over the course of just a few years.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, in the passage referring to the study looking at plaque progression, did not note that the difference based on viral suppression status in the rate of accumulation of lipid-rich low attenuation plaque was not statistically significant.

Benjamin Ryan (benryan.net) is POZ’s editor at large, responsible for HIV science reporting. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Comments

Comments