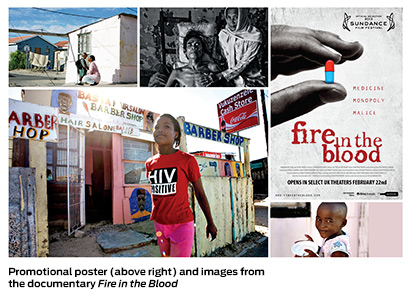

Although Fire in the Blood is his first feature-length film as a writer and director, Dylan Mohan Gray has worked on numerous feature films in dozens of countries. The film shows the struggles of introducing low-cost HIV drugs to developing countries, especially the hurdles connected with pharmaceutical companies.

Born and raised in Canada from a father born in Punjab, India, and a mother born in Ireland, he lives and works in Mumbai. Trained as a historian, Gray uses those skills to frame his story in terms of not only what happened but also what can be learned. He shares why he spent years on this film and what he hopes to come from it.

What is this film about, and how did the idea come to be?

Fundamentally, it’s about how people treat each other. A lot of films are about that on some level, but for me it always comes back to that. It’s about the degree to which corporate interests have overtaken human interests, how the business of health care has completely lost its bearings. It’s also about how the Global North treats the Global South.

I got interested in the topic when I read a newspaper article back in 2004. I was working on a film in Sri Lanka at the time and I just happened to have a day off. I picked up an old copy of The Economist and there was an article on the struggle over AIDS drugs in Africa. As the magazine tends to do, it took a very pro-corporate perspective. It seemed to me there was stuff going on between the lines that I found quite fascinating.

The other thing that interested me was the big Indian angle [because the country is such a large producer of generic drugs worldwide]. I then had a chance to meet Yusuf Hamied, PhD, the chairman of Cipla, an Indian generic drugmaker, through friends. I got to know him quite well and met some other characters in the film through him. I developed a very intense personal interest in it because I’m quite a political person.

As a historian, the historical aspect fascinated me, especially the fact that there was so little out there about it. When I started to look at things, it was all just contemporary news reports and piecemeal. I was quite scandalized that there hadn’t been any comprehensive account—in films or books or even long-form journalism. That was the thing that made this into a bit of a personal obsession for me.

A friend of mine one day said, “Why don’t you make a film about it?” It’s not that it hadn’t crossed my mind, but it seemed to me it had to be made as a documentary and I wasn’t a documentary filmmaker. Frankly speaking, I didn’t want to screw it up. It was likely to be kind of a one-shot deal. I did actually approach some other friends who were documentary filmmakers, and they rightfully saw it was going to take years of work.

Why did you decide to actually make the documentary?

A lot of people hadn’t talked about what happened because nobody ever asked, they had moved onto other fights or were so demoralized they retreated. There also were people who were diligently trying to get this story buried and create alternative narratives. I’ll give you one example.

The Age of AIDS was a four-hour PBS series in 2006 shot in about 50 countries and lavishly funded. It was meant to be the definitive account of the first 25 years of AIDS. They said the antiretroviral (ARV) cocktail had a miraculous impact except for all the people in the developing world who couldn’t afford it, then the drug companies were shamed into lowering prices and things got better.

I’m not necessarily blaming the filmmakers, but it’s a sin of omission. The drug companies were not shamed into lowering prices. They lowered prices because generics came in and nobody was buying their products. No one uses brand-name ARVs in Africa now, except for the third-line drugs for which there are no generic equivalents.

The PBS series also spent a small amount of time on how a huge proportion of people who died could easily have been saved. It was portrayed as a perfect storm of unfortunate circumstances. That’s not the case. My real objective in making the film was to set the record straight. I’m very comfortable with the content of the film and the veracity of it.  Please tell us more about the process of making this film.

Please tell us more about the process of making this film.

The people in the film are first-person participants in what happened. Everybody in the film can say, “I did this, they told me this, this happened to me.” That was an important part of telling the story as far as I was concerned.

One of the things we did right was starting in South Africa. It’s a place of activism and intellectual discourse around the issue. People like [Treatment Action Campaign co-founder] Zackie Achmat, [justice of the Constitutional Court] Edwin Cameron and [Nobel Peace Prize winner] Desmond Tutu were eager to get on the record. By the time we had done our shoot in Africa, especially in South Africa, we had gathered a lot of key people, which made it much easier to get people like [former U.S. President] Bill Clinton.

I also produced the film and did other things, like the poster picture. It was important to me to maintain a high level of creative control and maximize resources. That trade-off meant it took a few more years to complete than if somebody else had produced it.

What outcomes would you like as a result of the film?

The last section of the film raises the question of this all happening again, possibly on a much greater scale. Not necessarily so much in the field of HIV/AIDS, although there is a lot of danger there with access to second- and third-line treatments. Advocates are making it clear that they are not going to let HIV/AIDS go out of the limelight.

Not every ailment has that kind of a bully pulpit. It’s clear that the pharmaceutical industry and the governments working on its behalf do not want to make the fight for generic HIV/AIDS drugs to become a template for the future development and commercialization of other drugs. An example is the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a multilateral trade agreement that potentially affects 40 percent of the global population.

In terms of access to medicine, it’s horrendous [because leaked TPP drafts show the United States is allegedly seeking aggressive intellectual property provisions that enhance patent protections]. Advocates like Doctors Without Borders will tell you that it’s the worst trade agreement they’ve ever seen. The industry feels emboldened by the idea that there’s no opposition, so they see it as an opportunity.

The system incentivizes drug companies to behave in horrible ways. It dictates that they do not care about medications that affect poor people even though the markets are huge. Since their setup revolves around monopoly pricing, they are never going to be interested in the 90 percent of the world’s population that can’t pay thousands of dollars per month for drugs.

Somehow the narrative has been that it’s unfortunate some people have been left out, but that the current system is the best way for new medicines to be financed and incentivized. None of that is true. People have to recognize that the system is unsustainable. Once that recognition is in place, a lot of things become possible.

Go to fireintheblood.com to find viewing locations and more information.

Fire in the Blood

A new documentary warns AIDS advocates that the global fight for access to low-cost HIV drugs isn’t over.

1 Comment

1 Comment