This article was originally published on December 11 and updated on December 13, 2020.

On December 11, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted its first emergency use authorization for a COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer and the German company BioNTech. The emergency approval comes a day after an expert advisory panel voted overwhelmingly that the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the risks.

COVID-19 vaccine development has been remarkably swift. Early in the pandemic, National Institutes of Health director Anthony Fauci, MD, predicted that a vaccine could be available in 12 to 18 months, but tonight’s authorization beat even that optimistic timeline.

Today, FDA issued the first emergency use authorization (EUA) for a vaccine for the prevention of #COVID19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 in individuals 16 years of age and older. The emergency use authorization allows the vaccine to be distributed in the U.S. https://t.co/1Vu0xQqmCB pic.twitter.com/c8maeePP9O

— U.S. FDA (@US_FDA) December 12, 2020

“Today’s action follows an open and transparent review process that included input from independent scientific and public health experts and a thorough evaluation by the agency’s career scientists to ensure this vaccine met FDA’s rigorous, scientific standards for safety, effectiveness and manufacturing quality needed to support emergency use authorization,” FDA commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a press statement. “The tireless work to develop a new vaccine to prevent this novel, serious and life-threatening disease in an expedited time frame after its emergence is a true testament to scientific innovation and public-private collaboration worldwide.”

Emergency use authorization is not the same as full approval, and it is typically granted after a simplified review. But given the political controversy around COVID-19 and the large number of healthy people who would receive the vaccine, the FDA undertook an extensive review process that included an outside expert advisory panel and public comment.

Rollout of the vaccine is expected to begin as early as next week, although initial supplies will be limited. President Donald Trump has said the shots will be provided for free to the public.

Rapid rollout is crucial as the number of COVID-19 deaths approaches 300,000 in the United States and more than 1.5 million worldwide. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was authorized by the United Kingdom, Bahrain, Canada and Saudi Arabia over the past week. Mexico also authorized the vaccine on Friday. China and Russia are currently administering their own vaccines.

Health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities should be first in line to receive the vaccine, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advisory committee. Other priority groups include front-line workers who are at high risk for coronavirus exposure and people over age 65 and those with comorbidities, or underlying health conditions, who are at risk for severe COVID-19 and death. States and local jurisdictions will make the final decisions about vaccine allocation. Although prisons have seen large COVID-19 outbreaks, the committee did not prioritize incarcerated people. And it is not yet clear whether the vaccine is safe and effective for children.

Phase III Study Results

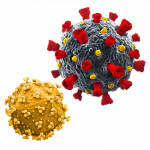

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, known as BNT162b2, employs a novel messenger RNA (mRNA) approach. The vaccine uses lipid nanoparticles to deliver bits of genetic material that encode instructions for making the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein—the red protuberances in the iconic virus image—which the coronavirus uses to enter human cells. When injected into a muscle, the cells produce the protein, triggering an immune response. The mRNA degrades quickly in the body, and it does not alter human genes.

No mRNA vaccines have been previously approved by the FDA, but the platform has been in development for many years. Once Chinese researchers revealed the genetic sequence of the new virus in January, Pfizer-BioNTech and another company, Moderna, were able to produce vaccine candidates within a matter of days. The FDA is likely to approve Moderna’s mRNA vaccine next week.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was tested in a Phase III clinical trial that enrolled more than 43,000 volunteers, three quarters of them in the U.S. Men and women were equally represented, and 42% were over age 55. More than a quarter identified as Latino, 10% were Black and 4% were Asian. Many had comorbidities, including obesity (about a third), hypertension and diabetes. A small number of adolescents ages 12 to 17 and people living with HIV were enrolled later in the study and were not included in the primary efficacy and safety analysis.

Study participants were randomly assigned to receive two doses of the vaccine or placebo injections spaced three weeks apart.

As described this week in The New England Journal of Medicine, the vaccine was 95% effective at reducing the risk of symptomatic COVID-19. A total of 170 cases were observed seven days or more after the second dose: 162 in the placebo group and just eight in the vaccine group. A protective effect was evident starting about 10 days after the first dose. Of the 10 reported cases of severe COVID-19, nine were in the placebo group. The single vaccine recipient classified as having severe disease based on low blood oxygen levels was not hospitalized and did not require advanced care.

The vaccine was effective across all demographic groups, including people over age 65. Within that age cohort, there was one case of symptomatic COVID-19 in the vaccine group and 19 cases in the placebo group. This was closely watched, because while elderly people are at greatest risk for severe COVID-19, they tend to mount a weaker immune response to vaccines.

The vaccine was safe and generally well tolerated, though many participants experienced mild to moderate side effects. More than 80% of vaccine recipients had injection site reactions such as soreness. Other common symptoms included fatigue (63%) and headache (55%); these usually lasted no longer than two days. Flu-like symptoms are not unusual after receiving vaccines and are an indication that the immune system is working.

Side effects were more common in people under age 55 and occurred more often after the second dose. About 5% of people over 55 and 3% of younger volunteers had severe reactions. Four vaccine recipients—but no one in the placebo group—developed Bell’s palsy, a sudden and usually temporary weakness or paralysis of facial muscles. There were two deaths in the vaccine group and four in the placebo group, most of them due to cardiovascular disease.

Days after vaccinations started in the United Kingdom, two National Health Service workers with a history of prior vaccine reactions experienced allergic reactions to the vaccine; both recovered. Pfizer’s safety information for the vaccine states that it should not be given to individuals with a known history of severe allergic reactions to vaccine components and that appropriate medical treatment for managing allergic reactions must be immediately available in the event of acute anaphylactic reactions following vaccine administration.

Responding to concerns, the CDC said that people who have had prior reactions to vaccines or injectable drugs can still get the new vaccine, but they should discuss the risks with their providers and should be monitored for at least a half hour after administration. People with other types of allergies do not need to take such precautions.

Unanswered Questions

On December 10, an FDA advisory panel voted 17 to 4, with one abstention, in favor of emergency authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for people age 16 or older. The dissenters expressed concerned about authorization for teens under 18, given the limited data for this group.

Other questions also remain to be answered. Vaccine response and safety have yet to be analyzed for the HIV positive people in the trial, and also have not been determined for people with immune suppression, autoimmune conditions or cancer. The vaccine is not contraindicated for such individuals—and experts do not foresee problems—but they should talk to their care providers about their specific situation.

“Since [it’s] not a live vaccine and no biological reason to be concerned about HIV, [I] would recommend those with HIV be vaccinated,” Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, medical director of the Ward 86 HIV clinic at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, said on Twitter.

“I do not believe there will be major safety problems specific to our cancer population,” Toni Choueiri, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, told OncLive. “The hope is to have at least one study in patients with cancer so we can answer the question.”

A trial for adolescents ages 12 to 15 is underway, and studies of younger children are planned. Another study will test the vaccine in pregnant people—an important consideration given that three quarters of health care workers are women, and a large proportion of them are of child-bearing age.

The BioNTech/Pfizer data is out—NEJM & FDA report. I understand this wasn’t in the design & the long-term protection from single dose is open question. But given this sharp drop after 14 days after one dose, can someone explain why single dose isn’t very very high on the agenda? pic.twitter.com/sxqwACGulz

— zeynep tufekci (@zeynep) December 10, 2020

In the Phase III trial, the risk of symptomatic COVID-19 fell by about half after the first vaccine dose, raising the possibility that while supplies are limited, it might be feasible to administer a single dose to a larger number of people right away (especially younger adults who tend to have strong immune responses), deferring the second dose until there is a greater availability.

It is not yet clear whether the vaccine will prevent asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection or transmission of the virus. Trial volunteers were not tested regularly to see whether they had been infected; they were tested only if they developed symptoms. Most experts expect that the vaccine will offer some protection against infection, but this remains to be proved in further studies.

It is also not yet known how long vaccine-induced immunity to SARS-CoV-2—or natural immunity after an infection—will last. However, earlier studies showed that this and other COVID-19 vaccines generate T-cell responses, which could persist even if antibody levels wane over time. People previously infected with SARS-CoV-2, many of whom are unaware of it because they were asymptomatic and not tested, can safely receive the vaccine, but it is not known whether it will give them extra protection.

Most experts expect that so-called herd immunity could occur after around 70% of people have been vaccinated. At that point, there would be too few susceptible people for the virus to spread easily, and even people who are not vaccinated would be protected.

“If we get 60% to 70% of people vaccinated with a vaccine that’s more than 90% effective, we probably will reach a point that’s pretty close to herd immunity, where the virus just can’t find enough mouths and noses that aren’t immune, and then it starts dying out,” Bob Wachter, MD, of the University of California at San Francisco, told COVID Health.

Stellar job by my colleague @ADPaltiel in conveying our work with @jasonlschwartz and Amy Zheng in @Health_Affairs. Major investments in vaccine distribution and trust are an essential next step to implementation. Vaccines don’t save people. Vaccinations do... https://t.co/kd2OyiqsyI

— Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH (@RWalensky) December 9, 2020

Reaching this level quickly will be a challenge given limited vaccine supplies. Pfizer has contracted to provide 100 million doses in the United States—enough for 50 million people using a two-dose regimen. If Moderna’s vaccine also receives emergency authorization next week, the total supply will increase. Other experimental vaccines—including an adenovirus vector vaccine from AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford and a one-dose candidate from Johnson and Johnson—may also be authorized in the coming months. The Pfizer-BioNTech must be stored at a super-cold temperature (minus 94° Fahrenheit), which presents logistical challenges around storage and distribution.

Persuading the population to get vaccinated will be another challenge. Some people are concerned that vaccines have been rushed through the development process due to political pressure. Some want to see longer-term safety data. Others still do not regard COVID-19 as a serious threat. Polls have found that African Americans and Latinos, who have higher rates of coronavirus infection and COVID-19 complications, are more likely to distrust the medical field and the government and are less willing to get the vaccine. Hoping to overcome such reluctance, a group of prominent Black doctors recently encouraged Black Americans to get vaccinated.

Although Operation Warp Speed chief scientific adviser Moncef Slaoui, MD, has said that about 100 million people could be vaccinated by the end of February, others think the process will take longer.

Many experts predict that adults under age 65 with no particular risk factors could start getting vaccines around April. Vaccination of this group could be completed between the summer and the end of 2021, depending on willingness and ongoing supply issues. The timeline for children is unclear.

Until then, it will still be important to keep up precautions to prevent COVID-19, such as wearing masks and social distancing.

Click here for more news about COVID-19 vaccines.

5 Comments

5 Comments