A new type of vaccine has resulted in successful control of SIV (simian immunodeficiency virus), the monkey version of HIV, in about half the monkeys who received the vaccine and were then later exposed to the virus. These findings, published online May 11 in the journal Nature, might offer a new avenue for vaccine research.

In the natural course of HIV infection, a person’s immune system often takes weeks after initial exposure to respond in a meaningful way to the virus, and though most people are able to naturally bring down HIV levels substantially, their immune systems never fully control it. Eventually, if people don’t receive combination antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, they develop AIDS and die.

Nearly every effort to find a successful vaccine to prevent HIV infection has failed because of the virus’s ability to change itself and avoid immune control. Efforts to provoke the immune system to better control HIV if a person does become infected—rather than protecting from infection in the first place—have also failed.

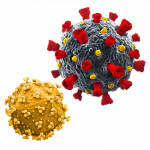

Aside from the difficulty they’ve encountered in provoking the right immune response with the right pieces of HIV proteins, experts have also had a hard time finding a delivery vehicle for those proteins—one that will trigger a strong and long-lasting immune response without causing harm.

Vaccine researcher Louis Picker, MD, from Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) in Portland, has been focused on this task for about a decade. He and his team have chosen the cytomegalovirus (CMV) as their delivery vehicle, referred to in scientific circles as a vector. CMV is widely spread—most people have been infected with this close relative of the herpes virus—and the effects of CMV tend to be minimal in the young and healthy. CMV has been tied in some studies to depletion and damage to the immune system in elderly people and some suspect that the same is likely to be true in people with HIV even when their CD4 counts are high.

In this experiment, Picker’s team vaccinated a group of rhesus macaques with an SIV vaccine that was delivered with the CMV vector; researchers then subsequently infected the monkeys with SIV. The team also infected a group of monkeys who weren’t vaccinated. Both groups were followed over time.

Picker found that while all of the monkeys who got no vaccine developed AIDS-like symptoms and died, only half the vaccinated monkeys became ill. In those who remained healthy, only tiny bits of SIV could be found in their blood and tissue, and some of the monkeys appeared to be on the way to eradicating the virus almost completely.

It is a long way to go from studies in monkeys to studies in humans, and much remains uncertain. Nevertheless, Picker is optimistic.

“The next step in vaccine development is to test the vaccine candidate in clinical trials in humans,” he stated in a release from OHSU.

“For a human vaccine the CMV vector would be weakened sufficiently so that it does not cause illness, but will still protect against HIV,” he concluded.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

3 Comments

3 Comments