People living with HIV can safely use a type of immunotherapy that is revolutionizing cancer treatment, according to a recent medical literature review in JAMA Oncology.

Although the number of HIV-positive people treated with checkpoint inhibitors in published studies remains small, these drugs appear to be a safe and effective option, concluded review authors Michael Cook, MD, and Chul Kim, MD, PhD, of Georgetown University in Washington, DC.

As people with HIV live longer thanks to effective antiretroviral therapy, non-AIDS-defining cancers have become a major cause of illness and death. Immunotherapy, which helps the immune system fight cancer, offers a promising new approach to treatment, although current medications do not work for all patients or all types of cancer. To date, there has been little research on immunotherapy in HIV-positive people, who have generally been excluded from clinical trials of new cancer therapies.

“Cancer patients with HIV and their oncologists have found themselves in a real conundrum. Because of their HIV infection, they are at higher risk of developing cancer than people who are not infected,” Kim said in a university press release. “But conventional chemotherapies can reverse HIV suppression, and on top of that, these patients are widely excluded from clinical studies that test the next generation of cancer treatments.”

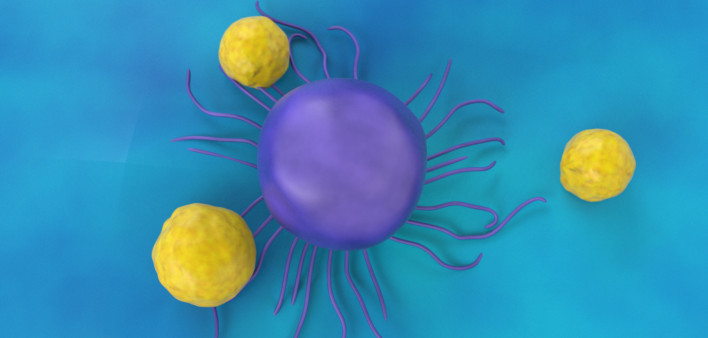

The most widely used type of immunotherapy, PD-1 or PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors, help immune cells recognize and attack cancer. PD-1 is a checkpoint receptor on T cells that helps regulate immune function. Some tumors can hijack PD-1 to turn off immune responses against them. Drugs that block the interaction between PD-1 and its binding partner, known as PD-L1, can release the brakes and restore T-cell activity.

Keytruda (pembrolizumab), Opdivo (nivolumab) and Libtayo (cemiplimab) are approved PD-1 inhibitors. Bavencio (avelumab), Imfinzi (durvalumab) and Tecentriq (atezolizumab) block PD-L1. CTLA-4 is another immune checkpoint that turns off immune responses by suppressing T-cell multiplication; Yervoy (ipilimumab) is the only approved CTLA-4 inhibitor.

Cook and Kim performed a systematic review, searching the PubMed database and abstracts from major HIV and cancer conferences for studies that mentioned HIV and any of the approved checkpoint inhibitors.

They identified 73 HIV-positive people treated with these medications, described in 13 articles and four meeting abstracts. Most were from case reports rather than clinical trials. About 90 percent were men, and the average age was 56. Among those with available test results, 95 percent were on antiretroviral therapy, and 84 percent had an undetectable viral load when they started checkpoint inhibitors.

A third of the identified patients (25) had non-small-cell lung cancer, followed by melanoma (16), Kaposi sarcoma (9), anal cancer (5), head and neck cancer (4) and various other cancer types (14). A majority were treated with Opdivo (29 people) or Keytruda (26 people), six used Yervoy, four used Opdivo plus Yervoy and several more used unspecified checkpoint drugs.

Checkpoint inhibitors were generally well tolerated. Just six HIV-positive patients, or 9 percent, experienced severe (grade 3 or higher) immune-related side effects—similar to rates seen in HIV-negative people. Of these, four had used the CTLA-4 blocker Yervoy. “No new safety signals” were observed, the researchers reported.

All but two of those with undetectable HIV prior to treatment maintained viral suppression, and CD4 T-cell counts increased slightly (average gain of 12 cells). What’s more, five of the six people who had detectable HIV before treatment saw a decrease in their viral load, and four of those achieved viral suppression. “It could be that checkpoint inhibitors are helping to suppress HIV, though this finding needs to be verified in future studies,” Kim said.

Prior research has shown that HIV-positive people may have high levels of PD-1 expression on their T cells—a sign of immune-cell exhaustion—and PD-1 inhibition could potentially play a role in immune reconstitution, the researchers noted.

Objective response rates, meaning complete or partial tumor shrinkage, were 30 percent for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and 27 percent for those with melanoma—again similar to response rates in people without HIV. The response rate was particularly high, at 63 percent, for those with Kaposi sarcoma, an AIDS-related cancer usually seen in people with advanced immune suppression.

“Immune checkpoint inhibitors may be a safe and efficacious treatment option in this patient population,” the study authors concluded. They added that several ongoing clinical trials will shed further light on the safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors for HIV-positive people with cancer.

“We hope our finding will lead to increased study of checkpoint inhibitors in patients with HIV and cancer,” Kim said. “There are signals in this analysis and other studies that suggest these new cancer drugs may restore an immune response against HIV in patients whose immune system is exhausted by its long fight with HIV.”

The National Cancer Institute recently expanded its clinical trial eligibility criteria to include people with certain coexisting conditions, including HIV, hepatitis B and liver or kidney impairment. A recent study by the SWOG cancer trials network found that expanding trial eligibility would allow thousands more patients to receive experimental therapies that could potentially extend or improve their lives.

Click here to read the study abstract.

Click here to learn about checkpoint inhibitors in HIV cure research.

Comments

Comments