Advocates from a variety of networks of people living with HIV held a roundtable discussion earlier this year. The topic of the day was the networks themselves and the value they can have in our communities.

The roundtable, held in New York City at POZ headquarters, was based on the belief that people living with HIV should be full, active participants in the response against the epidemic and in decisions that affect them, be it within the positive community itself, on boards for local AIDS service organizations, or in governmental policy-making efforts.

This fundamental human rights concept is rooted in The Denver Principles, a self-empowerment manifesto written in 1983 by people living with HIV/AIDS. The idea was advanced at the 1994 Paris AIDS Summit with the GIPA (Greater Involvement of People Living With HIV/AIDS) Principle.

Participants at the roundtable discussed the importance of networks in the lives of people living with HIV, the barriers to joining and expanding these networks, and the power such organizations can wield in addressing the epidemic.

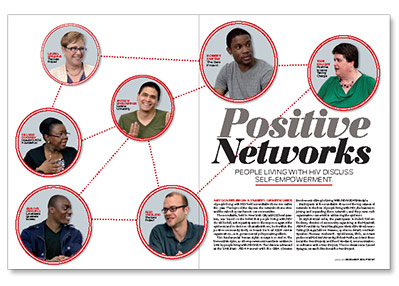

In alphabetical order, the participants included: Deloris Dockrey, director of community organizing at the Hyacinth AIDS Foundation; Tami Haught, president of Positive Iowans Taking Charge; Jahlove Serrano, spokesmodel at Love Heals Speakers Bureau; Andrew R. Spieldenner, PhD, assistant professor at Hofstra University; Robert Suttle, assistant director at the Sero Project; and Reed Vreeland, communications coordinator at the Sero Project. The moderator was Laurel Sprague, research director at the Sero Project and regional coordinator for GNP+ NA, the North American affiliate of the Global Network of People Living with HIV.

The following is an edited transcript:

Sprague: Why do networks of people living with HIV matter?

Serrano: When I was diagnosed, I thought I was the only person in the world with this disease. When I met a network, I met a family, I learned everything I needed to learn about HIV/AIDS. It empowered me to want to give back to my community.

Suttle: Connecting with a network gives me a sense of empowerment. It’s always been my hope to continue to connect with other people who are going through it, because we have multiple experiences.

Haught: When I was first diagnosed, for the first six years, there was complete denial. For example, my husband had “cancer”—we didn’t even say HIV/AIDS. It was so isolating, the burden of carrying this huge part of your life and not being able to talk about it. With a network, you can have a safe place to disclose your status and to get comfortable with yourself.

Sprague: For me, the networks have helped me find a voice. When I was diagnosed, it was in 1991. I was pregnant, I was in a relationship in which I didn’t have support. I came from a very religious family. I knew they would be ashamed, and they’d be afraid of me dying. I was afraid of me dying. I couldn’t tell anyone.

Then I found a support group of all positive men, and they saved my life. Those men taught me that I had value, that I could still laugh and that I could love. Most of them are gone, and I bless their memory for what they did. The other thing that they provided is what we call “treatment literacy”: the know-how to physically stay alive.

Vreeland: Having a space to connect with other people who’ve had similar experiences is very important—that seems so simple to say, but when you have a diagnosis like HIV, it really can feel overwhelming. You can discover friends, meet people who might change your life.

Spieldenner: When I was first diagnosed, I went to get tested with four friends, and we all thought statistically half of us would have HIV. Actually, all of us did. As an informal network, we didn’t have the skills to support each other the way we needed. We didn’t know what our agenda should be or how to access services or what the quality of care should be. I was able to join networks and get resources that could actually help change the way that services were provided to me.

It’s not just me chilling with my friends. I can articulate things that I’m going through. Also, I realized very early on that stigma is so pervasive that we can’t combat it as individuals. My first time in a dentist office, after I said that I was HIV positive, the receptionist started laughing. It was the worst feeling ever, and the only way I had to process it was socially, through networks.

Sprague: I feel like I can speak with more legitimacy when I know that my network agrees with what I’m saying.

Dockrey: I’ve been in a network of one sort or the other since about 2000. Oftentimes, a collective of people in a network will establish a policy agenda, and what it creates is a framework. These are frameworks that we can use as advocates in many avenues, whether we’re in the local community, the national community or in the global community.

Vreeland: One question I would ask is: What’s the alternative to networks? If you look at people with HIV in the United States today, the vast majority are not getting involved.

Serrano: Most don’t want to be the face of HIV/AIDS. A lot say, “It’s great what you do, but I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to be identified as HIV positive—the only time I want to remember that I’m HIV positive is when I’m with the doctors or take my medication.” Most HIV-positive people think like that, and I can’t blame them.

Suttle: There’s a danger in not connecting to a network. I’m not saying people need to be a face on anything. But if you’re not connected in any kind of way, whether it’s for treatment or for whatever reason, then you might be less informed about laws and policies that can impact your life. If you’re not aware of these things, you could find yourself either not having access to care or facing prosecution [for nondisclosure].

Serrano: But I’ve experienced stigma among HIV-positive people. Sometimes I didn’t want to go into a group that’s full of perinatally infected youth, because I was infected behaviorally, so they acted a certain way toward me. I felt that stigma, like, “You had a choice, we didn’t.” Having that said to me by my peers, it hurt. There are separate clinics for perinatally infected youth and behaviorally infected youth, because they don’t want to be among each other. Separate networks are already happening, and people are feeling this tension.

Dockrey: I am glad you raised that, because it underlines the fact that there is still a lot of work for us to do. Oftentimes, in the United States or in Canada, there’s a feeling that we have medication now, we’re living longer, everything is grand. But there are still lots of issues around stigma and access that still need to be addressed. I’m old. My issues are not the issues of young people who are just coming in, but we can share our experiences—and where better to do it than in networks?

Sprague: And to hold ourselves accountable for when we are not making people living with HIV welcome.

Spieldenner: Sometimes when we’ve lived with HIV for a while, we can’t hear some of [our own shortcomings]. For instance, I was working with a group of 40- to 50-year-old men in Fort Lauderdale, and they wanted to work with gay youth; they were insistent that gay youth was the priority. They had set up this conversation where if you were a gay man in your 40s or 50s who became positive, you should’ve known better.

Haught: I was shocked the first time I heard that long-term survivors were blaming the newly diagnosed. In education work, in schools or in colleges, nobody’s talking about HIV anymore. Since HIV is part of long-term survivors’ entire lives, many just automatically assume that everybody else knows about it. We’re losing another generation, which really worries me.

Spieldenner: Our networks have to be large enough for us all to have those conversations. So even if we feel like, “You are dumb,” there should be a space for that “dumb” voice, just so the other people know that their voices matter too. Vreeland: The network is a resource. Are you doing a good job? Who is going to know better than the young person you’re teaching, or the person who’s newly diagnosed? Those are the people you should be speaking with. And don’t be scared of it.

Vreeland: The network is a resource. Are you doing a good job? Who is going to know better than the young person you’re teaching, or the person who’s newly diagnosed? Those are the people you should be speaking with. And don’t be scared of it.

Haught: The community has changed so much. We are living longer, and the long-term survivors can mentor the newly diagnosed, but at the same time, long-term survivors can learn from the newly diagnosed. Everybody has a story.

Sprague: Why does it matter for people living with HIV that our networks are at decision-making tables?

Dockrey: I train advocates, and I tell them: “Before a regulation hits you at the clinic level, a decision has been made, and by the time it hits you, it’s too late.” We have to understand the structure of government. We are at every level of the decision making, and we have a right to be there as citizens. Networks help us pinpoint whatever issues are relevant. It’s important for the outside world to know that HIV is still here, it is still devastating, people are still dying. Who better to help our community than us? We need to be out there; we need to be examples.

Serrano: To be part of decision-making tables feels so great. It helps me let people know that I am more than just a number. It’s important for them to hear me. I love legislative day. I’m up there speaking to my local congressman, and I say, “In my community, we need more clinics, we need X, Y and Z, and guess what, I have a whole positive network that’s registered to vote, so you might want to take a look at it.”

Sprague: Why should organizations listen to us?

Spieldenner: Organizations and providers do want to give better service. They don’t always do it in a way that’s productive or beneficial to us. It’s important that networks of people with HIV are a part of supporting people with HIV to get needs met in a culturally competent manner. We have expertise in doing that.

Sprague: It’s important to send the message that we’re not a problem. We’re a solution.

Serrano: Our networks need funding, but isn’t networking free? Shouldn’t it be free?

Dockrey: It’s free to join, but to be effective, some funding is needed. Most networks operate on a shoestring budget. The members of the networks volunteer, so the work becomes piecemeal. It could be done better if we had little pots of money to hire part-time workers—to create our websites, update the blogs, or help with the accounting, answer the phones.

Spieldenner: Tami [Haught], you set up a network in rural America, so tell us about those budgeting issues.

Haught: Talk about a shoestring budget. For PITCH [Positive Iowans Taking Charge] it’s still volunteer. For CHAIN [Community HIV/Hepatitis Advocates of Iowa Network], luckily, we have gotten some funding. If we hadn’t received the funding we wouldn’t be as far as we are today. Not that volunteers aren’t dedicated, but you just don’t have the time or capacity to dedicate as much time as you want. In most of our rural communities and low incidence states, the funding is even harder, because we live in conservative communities. It’s taken us twice as long to get done what we wanted to do—or five times, 10 times longer—because we don’t have funding.

Sprague: What other barriers do you see for networks?

Haught: In rural Iowa we have transportation issues. We don’t have subways, we don’t have trains, we don’t have buses. And most people living with HIV in Iowa live well under the poverty level, so they don’t have vehicles. Everything is two and a half hours away. We have to go more with social media and conference calls, but you miss that personal connection.

Serrano: One of the challenges is the attitude of, “If your goal isn’t my goal, why should I network?” We need to see the bigger picture involved.

Vreeland: Different groups all want a seat at the table, and there’s only a certain amount of funding for any AIDS service organization, or a certain amount of grant funding. This pits different groups against each other. Networks often are able to get around that, but sometimes they play into it.

Dockrey: It’s also a question of solidarity. This is a huge country, and I find that local networks are not necessarily connected to the national networks. There is a disconnect. So how can we work together?

Suttle: Sometimes you’ve got to partner with organizations that are bigger and have capacity. I have seen it work.

Dockrey: I got the opportunity to co-chair the community planning group for the last International AIDS Conference. I found so many networks across the United States. There is not one place where everybody knows where all these people are. People are doing great work, but we’re not connected.

Sprague: We really need to build infrastructure just so we can know who else is out there and what they’re doing.

Suttle: Regardless of what key populations we’re in, whether it’s men who have sex with men, transgender people, positive women—in terms of HIV, all our voices can be heard at the same time. HIV impacts all of us. It affects us all.

Sprague: This has been an incredibly valuable discussion, and I appreciate the contributions from all of you. It’s a model of what we’re talking about: The value of networks of people living with HIV. We demonstrate why we need to bring our different experiences to the table. What we share in those experiences gives us combined strength so that we can make things better, bring policy changes—and work for our own well-being, and the well-being of other positive people.

For additional information about positive networks, visit the United States People Living with HIV Caucus (US PLHIV) website at hivcaucus.org

4 Comments

4 Comments