|

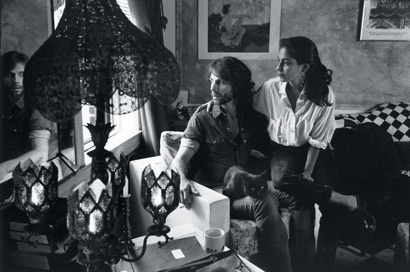

| A GMHC client with his buddy, circa 1990 |

Comfortable in some of his identities—black man, mental health care provider, father—Washington took some time to grow comfortable revealing other aspects of himself: gay and HIV positive.

But Washington, then in Chicago, got involved with the Cook County buddy program in 1984, in which he acted as friend and helpmate, or “buddy,” to people incapacitated by AIDS. The experience forced him to learn to be comfortable with graver matters than perceptions of his sexuality.

Washington’s buddy lived for nine months, during which time they became almost constant companions. “It was the first time that I was a witness, an intimate witness, to the dying of somebody. And it changed me,” he says. Although he is a psychologist, Washington had no formal training in work with death and the dying at that point, so he acted from the gut.

He recalls, “When it became clear he was going to die, he called me and told me. I picked him up—literally, I had to pick him up and carry him down the stairs—and took him to the Cook County Hospital. He died peacefully, a couple of months after his 21st birthday.”

With little money and few resources, but an abundance of compassion and solidarity, the HIV/AIDS service organizations LGBT people created from scratch in the 1980s sponsored buddy programs and other services. Thousands of other AIDS “buddies”—many gay, others not—had personal experiences much like Washington’s.

On June 5 of this year, New York City’s Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) announced it would relaunch its historic Buddy Program to help meet the needs of long-term survivors. As a journalist who has reported on HIV/AIDS for three decades, I recognized this wasn’t just another press release.

Nor was it just an acknowledgment that people who have been living with HIV for many years have unique challenges—including isolation, the stresses of living with chronic illness, and the high risk of depression, substance abuse and suicidal ideation.

I’d go so far as to say the revival of the GMHC Buddy Program is a reaffirmation of LGBT America’s heroic legacy in the AIDS plague—a reminder of how profoundly, and creatively, our people showed the world what love in action looks like, even in our darkest hours.

The first AIDS buddy program was created by the Shanti Project in San Francisco in the epidemic’s earliest years. To help people with AIDS take control of their lives and function as normally as possible, Shanti’s buddy program—along with the GMHC program, originally launched in 1982, and others like it in communities across the country—helped out with practical matters, such as grocery shopping, cleaning and cooking.

Typically, buddies weren’t expected to provide emotional support. But it’s probably impossible to come as a stranger into someone’s home, help him to retain his dignity and ability to function, and not become a friend.

In many cases, gay men had no one to count on. Families were often far away, possibly alienated. Good-time friends stopped calling. Fortunately, there were many “buddies”—people who, though probably also living far from their own families and perhaps their pasts, understood the importance of connection to others who cared.

We can be proud of how LGBTs and our supporters demonstrated love for one another in the past. Recommitting ourselves to support one another’s health and well-being going forward is the best possible way we can mark and celebrate our continuing LGBT pride.

Comments

Comments