The following is an excerpt from an article published in the October 2013 issue of Treatment Action Group’s newsletter, TAGline.

|

| Click the image to view a larger version. |

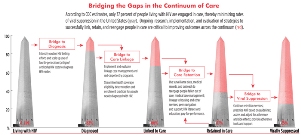

Viral-load suppression remains the holy grail of HIV care. Its associations with AIDS-free survival and a profound reduction in transmission risk are well established. To maximize the odds of getting viral load undetectable and keeping it there, numerous safe, effective, and miraculously simplified HIV drugs and fixed-dose combinations have been developed and approved. But there’s a problem: far too many people living with HIV in the United States--and elsewhere around the world--aren’t accessing the care they need to benefit from the personal and public health benefits of antiretroviral therapy.

The good news is that roughly 75 percent of HIV-positive people who are engaged continuously in care have suppressed virus. The bad news is that this accounts for only one in four of all people with HIV residing in this country. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV continuum of care--also known as the treatment cascade--only 62 percent of people living with HIV have been linked to a care provider, and an abysmal 37 percent are engaged in regular care--the initial steps required to get HIV-positive people on treatment.

Not surprisingly, cascade outcomes differ according to the population analyzed. According to the CDC, 62 percent of African Americans living with HIV, compared with 71 percent of whites, have been successfully linked to care. And whereas several states and municipalities have reported linkage and retention estimates that are below those of national cascade averages, others are reporting more encouraging outcomes. Massachusetts is a prime example: of those who have been diagnosed, roughly 99 percent are in care, and 71 percent have current or sustained viral-load suppression.

Interventions to the Fore

Barriers to care, which are myriad and overlapping, have been well characterized in the literature. Largely missing are data supporting successful approaches that can be scaled up to overcome these barriers. Whereas we have hundreds of clinical trials and other prospective studies to determine which HIV treatment regimens to use in particular circumstances, the evidence base needed to inform engagement-in-care practices and policies is limited at best.

This is not to say that interventions do not exist. In fact, numerous clinics and organizations have, for decades, been employing tactics to get people tested, into care, and retained in care. When it comes to engagement-in-care strategies, real-world experience far exceeds the science. But where there is a dearth of evidence-based practice, there may be much to be learned from practice-based evidence.

Among the interventions that have been shown to be effective, albeit in limited and often informal studies, are: strengths- and empowerment-based linkage case management (the only engagement-in-care intervention evaluated in a randomized, controlled clinical trial to date); medical case management, with a focus on helping patients get critical ancillary services providing food security, transportation, and housing; intensive outreach; reengagement case management; and systems navigation, an intervention that employs peers or paraprofessionals to help clients identify barriers and available services.

Another intervention being evaluated involves financial and nonmonetary incentives for patients who remain in care and on course toward positive health outcomes. Red-carpet entry programs, whereby newly diagnosed individuals are swiftly and supportively brought into care, are also being explored, as are recapture programs, whereby electronic medical record data are synced with surveillance data to identify individuals who have fallen out of care.

Evaluation and Translation

The scale-up and adoption of these and other practices, particularly those that have the potential to work in different populations and geographies across the continuum of care, require multidisciplinary research. Not only is this needed to better understand how to support the engagement needs of those who have not yet been successfully retained in care, but it is also necessary to minimize the risk of attrition among those currently relying on these services.

Expanding the evidence base, notably controlled clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of innovative approaches and prospective cohorts to further validate the outcomes and cost-effectiveness of established interventions, is essential, particularly if we’re to fully establish best practices to overcome barriers to care. Such research, however, isn’t cheap, and linkage/retention intervention protocols will require financial commitments from the National Institutes of Health.

Interventions also need to be scaled up. To ensure effectiveness, we need to determine in which settings interventions may be necessary, the motivators and barriers associated with their uptake, and ways to tailor the interventions while maintaining fidelity to their proven methodology. It is here that we can deploy implementation science, a rapidly evolving field of research, to determine how best to translate proven interventions into clinical practice and further validate their role in improving all aspects of the continuum of care.

Implementation science begins with the understanding that “top-down” clinical trial efficacy does not necessarily translate into effectiveness and efficiency in the real world, in large part due to social, behavioral, cultural, and service-delivery factors that exist outside of the research setting. The “bottom-up” approach to implementation science involves collaboration between service providers and people living with HIV to answer critical questions about effective translation of proven innovations--a number of study frameworks, characteristics, and methods are described in the literature--while at the same time yielding scientifically validated implementation strategies and outcomes measurements that can be disseminated and replicated elsewhere.

The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which was initially concerned with reducing AIDS-associated morbidity and mortality as quickly as possible in lower-income countries and did not at the outset include research, now supports implementation science to ensure that evidence-based engagement, prevention, and treatment strategies are evaluated and translated into sustainable, locally owned practices.

It’s now time to develop and implement a domestic implementation science research agenda. This will require the Office of National AIDS Policy to coordinate the resources and capabilities of many U.S. Department of Health and Human Services agencies, along with critical input from state health departments, health and social service providers, activists, and people living with HIV. Encouragingly, this cross-agency collaboration has already been put into play, with President Obama’s July executive order for an HIV Care Continuum Initiative (see "A Commitment to the HIV Continuum of Care," by Scott Morgan, also published in the October 2013 issue of TAGline).

To achieve the HIV disease management goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy as we prepare for a substantial shift in the U.S. health care delivery framework, a nationwide push is needed for the necessary evidence-based research and science-driven implementation to maximize engagement in care. We’ve made tremendous progress in our ability to safely and effectively treat HIV over the past 25 years. We now need to ensure that its lifesaving and transmission-preventing potential isn’t limited to only 25 percent of people living with HIV.

1 Comment

1 Comment