|

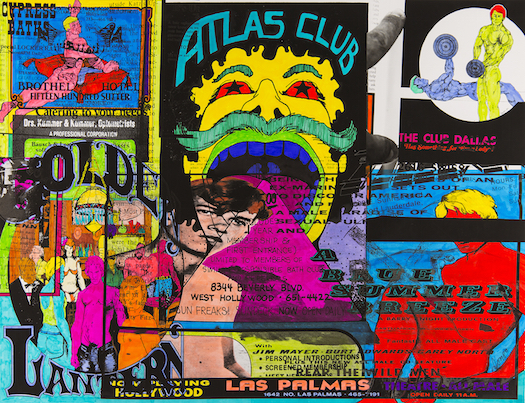

| Gabriel Martinez, “Untitled Series (Atlas Club)” (2014). Prismacolor on archival inkjet print, (unique print). |

Alex Fiorentino responds to and interviews Gabriel Martinez about his recent exhibition, Bayside Revisited, at the Print Center in Philadelphia.

The series of recent work by photographer Gabriel Martinez presents his deep nostalgia for a bygone era, a time of sexual liberation for gay men in America that found its oasis not only in the clubs and on the docks in New York City, but in the utopia of sun-bleached wood, white sand beaches and oiled bodies of Fire Island. Here, isolated from the mores of the straight world, pure hedonism could abound between men, as disco music played long into the night and beautiful naked forms copulated in and out of doors.

A series of small, framed collages flank the entry of the exhibit, using ephemera from 1969 to 1981 collected from the Wilcox Archive at the William Way LGBT Center, mere blocks from the gallery. These images consist of ads for bathhouses, clubs, and porn theaters, all related not only to publications for gay men, but queer spaces in which gay men were able to act on sexual desires. These are at once flamboyant in their bright Prismacolor kaleidoscope, but also suggest a coloring book, one that Martinez thinks would teach the younger generation a thing or two:

“I was kind of thinking about myself and my role as an artist right now, as a middle-aged artist, as a mid-career artist, as a kind of narrator, a kind of conduit from the older generation passing on information from the older generation and translating it for the younger generation, because I felt that sometimes the younger queer generation isn’t as informed as they should be, as to the struggles that led to this period where we’re at now, talking about equality, and there were a lot of folks back in the 70s that gave their lives to create the freedoms we are experiencing now. And so I kind of thought this was a sort of cheeky lesson for the younger generation like ’Okay, class, Queer History #15: let’s color in this graphics because it is an integral part of our history.’ ”

This also stems from Martinez’s own adolescent experience as a young gay man, when homosexuality was still very much associated with “shame, and death, and guilt.” Martinez says, “It was a tricky time period coming out during the 80s. And of course I was still young and somewhat naïve so I wasn’t as intensely part of ACT UP as I look back now I should have been."

While being out was still dangerous territory, that did not stop a young Martinez from viewing the counterculture becoming popular culture during the ’70s and ’80s, when Fire Island was becoming a venue for the greats of disco. We discussed his early obsessions, particularly Donna Summer, who plays a large role in the work that first greets the viewer before they enter the main space:

Martinez: There were certain things as a child that I gravitated toward: The Village People, Donna Summer. The first time I ever heard of Fire Island, this mythical place, was through the Village People actually. And I was obsessed with Donna Summer, like ridiculously. I would play her albums every day all the time. I had posters surrounding all aspects of my room. Now a lot of the work I have created for this exhibition actually stems from Donna Summer, of all people.

I did this project called Anthology where I destroyed Donna Summer’s records and I converted them and I painted on them. About six months after that project was complete, Donna Summer passed away. And, so I really started to think about her and that’s what started my further research for queer history and that time period.

Well this piece is not only like a weird amusement park entry into the main gallery, but it also is an image that I took on the seashore of Fire Island (January 2014). What I did was a placed Donna Summer’s iconic Live and More album, the cut out album, on the seashore and let the salt water and the waves take her away. And so you see this image that almost looks like a weird photoshopped cutout but its not. I popped the flash to bring her out and that’s the kind of dreamy, sort of sunset of Fire Island’s seashore.

That’s beautiful.

And so, it always feels like tears, salty tears. So the other thing about this is that this image, or this photo I created, is during the summer of 1979, the height of so much: the height of disco, the height of her career, the sexual revolution was at its peak.

Donna Summer was scheduled to perform on the seashore of Fire Island in front of 5,000 LGBT folks. And she canceled last minute, and people were like “What the hell?” And people were also thinking, you know, maybe she didn’t want to be so closely associated with the queer community, because that would disrupt her commercial appeal. But people were also speculating that was the beginning of her “born-again” phase, perhaps.

Right, which I think is something that’s super iconic, her feelings about gay men during the AIDS crisis, that it was brought upon them.

And she says that statements associated with her dealing with shame and guilt and the gay community were misconstrued or she never said them. So we’re still not quite sure what the truth was. But her career and the death of disco began in 1981, which is interesting because that was the very beginnings of the AIDS crisis. And so, what I’ve done here is have Donna Summer perform for the first time ever in Fire Island.

The printed image of Summer doubles as the curtain into the dark exhibit, where one comes face to face with the source of the sweeping cinematic music that could be heard from the entrance. This is in fact that soundtrack to Wakefield Poole’s 1971 classic “Boys in the Sand,” the “most important gay porn ever made, because this is the one that started everything, the whole ‘porn chic’ situation of the 70s." With permission from the director, Martinez evokes the Fire Island of that time, the setting of the film and the focus of the majority of the work in “Bayside Revisited.”

The film reflects off of a mirrored disco ball from a traditional film projector, one that would have been used when the film was first shown places like 42 nd street. This creates a magical, wave-like effect of tiny green bubbles containing boys romping on the shore that ripple on a backdrop of actual sand from Bayside shore (the show’s namesake) and glitter for good measure.

This takes the viewer to the next work, a slideshow of 80 black-and-white night shots of the infamous Meat Rack, a forest known for cruising. These small projections possess equal parts Eros and Thanatos, the nature of public sex being both carnal and anonymous. The anonymous aspect of this nocturnal ritual had its consequences, for just as sex took place in the dark, so was a public knowledge of what would later be known as HIV and AIDS. “[Fire Island], especially the Meat Rack, is like a memorial to hundreds of thousands of lives that were lost,” says Martinez.

Loss is a major driving force of the work: a loss of people, a loss of places, a loss of innocence, and the loss of a culture. Live Hard, 2015, presents the secretive “hanky code” of the day in a particularly sinister manner, the blackened bandanas shown grid-like and laser-etched with the image of the island. This process, echoed in several other pieces, alludes to Fire Island’s history of actual fires, which have destroyed much of the wooded oasis even into more recent times. Martinez finds metaphor in the fires to the disease that forever altered the carefree sexual atmosphere, the work an elegy and a reexamination of an era remembered for its excess, decadence and long nights danced away in the disco heat.

Alex Fiorentino is a Philadelphia-based writer and art historian who regularly contributes to theartblog.org and Visual AIDS.

Comments

Comments