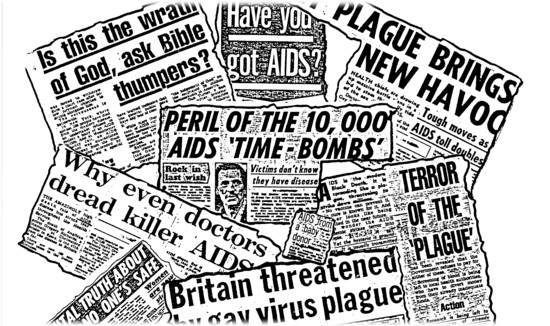

It’s sometimes difficult for me to believe but as I come upon my 28th year of living with HIV, I’ve come to realize I’m part of a special group. Not only am I considered a long-termer but I also consider myself part of what I call, the generation of ’First Wavers of HIV’. I define this term as those who have been exposed to HIV since it’s discovery in the 80’s and early 90’s. For those unaware, it was an interesting time, to say the least. There were many firsts that those newly diagnosed couldn’t comprehend. It was a time of fear, not knowing what exactly this virus was and how to stop the spread . Accusations and conspiracy theories were given life. People were blaming the virus on everything, Haitians, the government, African monkeys and even a flight attendant. The way people had sex was transformed as everyone was now suspect, especially gay men. And although over the years some things have changed, sadly the fear and stigma of HIV remains the same.

The first time I heard of AIDS I had no immediate fear. Everywhere you looked, you would see the word displayed in bold red letters which screamed danger. From the headlines of national magazines to the leading story on newscasts. At the time it seemed to only affect gay men. I didn’t consider myself gay therefore my concern was small. It also seemed the only ones greatly impacted were white men, so AIDS wasn’t truly on my radar. But it was obvious others were talking about it as the very mention of the word struck fear.

This fear was born from the fact nobody knew the answers of how you could get HIV. Could you get it from sharing an eating utensil? Would you contract it by giving someone a hug? No one knew. It seemed there was a lot of guessing on what to do and who to avoid. I recall my own moments of having wrong information dispensed to me. It happened when I was diagnosed with the virus and a health nurse came to my home to show me how to use hot water and bleach to wipe my toilet seat clean, in order to prevent anyone else to contract my HIV. My response to her was not one of anger but learning as it was the only information anyone had about the disease at the time. It seemed her information was contagious as it became a symbol of how misinformed information could spread. Yet again that was the environment.

During the early days the word HIV didn’t exist. During my own diagnosis I was told I had HTLV-III which today we know as HIV. It was even referred to as GRID (gay-related immune deficiency) by others. All the terms were the same and It simply meant, although you had the virus, it had yet advanced to AIDS. Little consolation but something that still inspired hope.

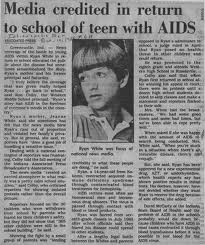

By now people are familiar with Ryan White, a 13 year old boy who was diagnosed with HIV in the 80’s. It’s suspected he got HIV from blood that was tainted during a lung operation. He was a poster child representing people’s fears. His presence at school caused alarm and a move was made to ban him from the school grounds. It wasn’t uncommon to hear on the national news how communities were attempting to ban someone from swimming pools or any public facility. The thought of that happening today would be outrageous, but unfortunately in the 80’s it was the norm.

I think we all were shocked when we saw the gaunt face of Rock Hudson. Always considered a Hollywood hunk, many fans were unaware of his sexuality and equally surprised when he was diagnosed with AIDS. Always a striking leading man he now looked thin and frail, with cheeks sunken in. You can say this was the beginning of the form of stigma when a person felt they could tell who had HIV simply by the way they looked. The joke among comedians and people on the city streets was the perception that based on a person sudden thin appearance, they most likely were either on crack or had AIDS.

It was a scary time for those living with the virus as medications options were little to none. Unlike today’s large category of HIV drug options, the only pill that existed was AZT. Many took the pill despite the imperfectness of it and the unknown question of whether it would work. I chose not to take it myself as I was scared of the reported side effects. I also felt it would make my situation worse as it wasn’t a sure thing. It felt so temporary and I didn’t want to be a trail monkey for the drug. So I went without medication during the first 10 years of my diagnosis.

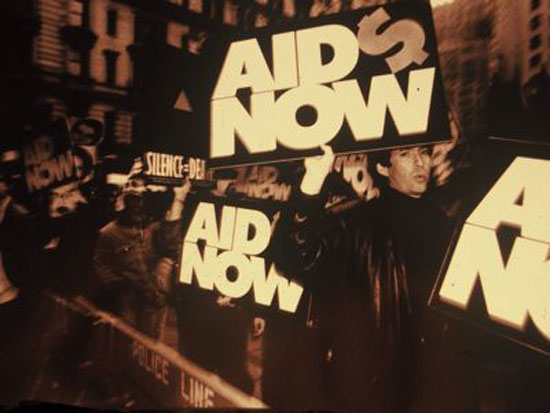

As crazy as it may seem, for those who experienced those early days, we can sit back and reminisce and affirm on how fortunate those who are exposed today have it easier than we did.This statement is not meant to say anyone recently given a positive diagnose finds it any less difficult knowing your status, but the environment and resources have greatly improved since the time I was tested. With the success of today’s HIV medication, people newly exposed today may be unaware of the devastation the virus was causing in the community. Not only was AIDS making the national news, but people were dying around us. Attending funerals and losing friends and loved ones was the norm. The idea that AIDS was a death sentence was born from the numerous funerals one had to attend. Today people are still passing away but not in the numbers they once were.

Finding support was difficult back then compared to today. We didn’t have a thing called the ’internet’ or social media to find support. It felt like we were alone with no one to tell our story. There was no type of HIV funding for those who had other struggles, such as poverty and homelessness or simply lacked the funds to purchase medications. No community based agency existed to go to for answers or resources. It felt like we were on our own. We stopped dating as we knew the rejection was worse than the disease itself. Unlike today where some are more open minded. There was not such a thing as "Undetectable’ to form a decision of whether to have sex with a person. You were simply undesirable based on the virus you carried, left to feel your status is a scarlet letter where both communities, gay and straight shunned you.

There can sometimes be a disconnect between the ’First Wavers“ and the generation today as they don’t have the comprehension of previous HIV battles. Sometimes it may feel like there exists a unappreciative response to the community of those in the first wave. Many benefits such as funding, resources and the creation of many community based HIV specific agencies were created by the ’First Wave”. Yet to look at the current HIV outreach and messages, they seem only directed to the Second generation. Our stories are being replaced along with our faces. We’re forgotten and it sometimes feels like we’re not invited to today’s battle. If we are, it feels more like an accommodation. There can be a value of inserting our history in the dialogue today and align it with the outgoing prevention messages. The youth are our future and currently being impacted but we also can’t forget those who came before as we’re still here.

There is so much each generation can offer to each other and so many lessons shared from our histories. I’m fortunate to be part of this group of men and women who have weathered the storm but also realize there are more battles ahead. And as we get older, we will create more roads of learning as we create a template on how to grow old with HIV.

Those were the days and ones I hope we won’t have to repeat. There exist many obstacles when it come to HIV but looking back at our history we can see our battles have made some difference. For our new soldiers they should be encouraged and know victories don’t rise overnight. But with your hard work, the second generation will be able to look back and hopefully document the progress made and lessons learned. Already we see signs of further acceptance with high profile individuals coming out with their status, numerous articles and blogs of people telling their stories and even dating sites exclusively for the HIV population. Advances we didn’t see happening in the early days.

Those were the days and together we can make a difference for the coming ones as we look back on our HIV.

2 Comments

2 Comments