When we first meet Vishwas Pethe in his memoir, Gay Crow, he is 62 and ready to end his life—not because he’s depressed or angry but because he’s “tired of fighting.” In 2016, the Indian-American computer engineer (he was one of the original developers of Grindr) suffered a debilitating stroke and fall. What’s more, these setbacks arrived after he’d been diagnosed with AIDS in 1986 and then non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a type of cancer, in 2001. That’s a lot of fighting.

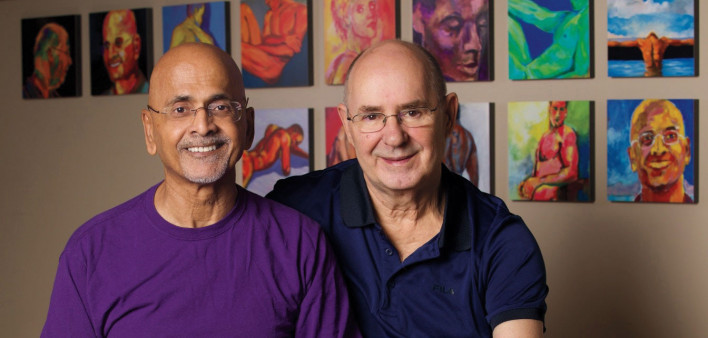

At the insistence of his partner of 30 years, husband Joe Hennessy, Pethe agrees to see a psychologist. The conversations between Pethe and his therapist, Carl, constitute the bulk of book. Through this unconventional Q&A format, Pethe’s amazing life story unfolds—growing up in India; coming out; surviving his first partner, who was lost to AIDS; enjoying career successes; marrying Hennessy; and much more. Along the way, Pethe and his therapist matter-of-factly explore deep philosophical questions about what constitutes a happy and healthy life. POZ spoke with Pethe, who turns 67 in June and lives in Falls Church, Virginia, via email and Zoom. The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

First off, tell us about the book’s title.

Gay Crow is a pun on the famous Indian childhood story called “Happy Crow.” The gist of the story is that there was a crow living in the jungle who was always happy. A king hears about it and decides to make him unhappy. He tells his soldiers to capture the crow and put him through different punishments. But the crow finds something in each circumstance to be happy about. So finally, the king lets the crow go and says we should all be happy like the crow. My uncle called me a happy (gay) crow watching me play with others when I was a kid because I was always happy.

What were your goals—for yourself and others—in writing the memoir?

I noticed that being happy made me forget the bad things that come by in life. I always found something to be happy about and never remembered the bad things. When I talked to the therapist, it became clear to me that it might be a secret to my survival. Then I thought, Why not document this and let others in similar situations find a way out? My memoir can help people coming out, adjusting to a different culture or dealing with health problems.

What was your rationale behind considering suicide?

The left side of my brain was gone, my right arm was not working, my right leg was not working and my speech was disabled. My last fall put my left arm in plaster, and my jaw was twisted. I was on a liquid diet. My sharp mind and intellect were gone. This is on top of the years I had spent fighting AIDS. I was tired of fighting. That’s why I was choosing suicide. What kept me from doing that was my love for my partner. I imagined what his life would be with me gone. I wanted to spare him the trouble. What changed my mind is that Carl kept up my interest in psychology and that bought time while my condition improved to the point I could manage it. At no point was I depressed.

Your HIV journey has been challenging as well. In 2006, you developed resistance to HIV meds and were diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma—an AIDS-related cancer—until you got into an Isentress (raltegravir) trial, which gave you a second life. How is your HIV now?

My viral load has been undetectable since 2006. But after having a number of treatments and each having its side effects, it has taken a toll on my system. I have osteoporosis [bone loss, a potential side effect of certain HIV meds], adrenal insufficiency, hypogonadism [low testosterone], weakness in the right ankle (a result of the fall in 2001) and other age-related problems.

Is there a specific outlook or physical trait that helped you persevere?

My gay crow attitude is the thing that kept me going. As I look back on my life, I only remember what a wonderful life I had. I take notice of the negative things and deal with them, but they don’t stay in my mind once they are gone.

That sounds like sthitapradnya, which you mention in the book. How would you describe this?

Sthitapradnya has various meanings. The one I go by is the state of mind that is not disturbed by good things, nor is it disturbed by bad things. You separate the mind as the inner mind and the outer mind. The outer mind reacts to good or bad things, but the inner mind stays stable. It has helped me handle the HIV and the stroke as things that happened outside but didn’t affect me inside.

When I picked up your book, I expected to learn more about a Hindu view of the LGBTQ and HIV experiences, only to discover you’re an atheist.

First of all, you must understand that Hinduism has nothing to do with God. You can be a God-fearing/-loving Hindu or an atheist Hindu. As someone said, Hinduism is not a religion but a way of life. Many Hindus don’t believe in God. So my being a Hindu did not affect my being gay, but the societal attitudes did. I knew that society would not understand it, so I kept it my secret. Coming out was the same thing. I only came out to people that I thought could handle it, though I never lied about it.

I get the impression that you’ve not struggled with hang-ups and shame regarding being gay.

Yes, that is very correct. I have never met anyone that shamed me for my sexual preferences. It’s surprising that not one person [I know] has any problem with the gay thing, including my extended family and friends here and in India.

You’re up-front about having open relationships with your long-term partners. Have you received any push-back about that in the age of marriage equality and heteronormative, monogamous relationships?

All men (not women, I am not qualified to analyze them) are promiscuous (in a good way). Men want security and freedom. Having a relationship gives them security, but they lose freedom. Being single gives them freedom but no security. An open relationship achieves both. I have not had any pushback from anyone. A more heteronormative, monogamous gay “lifestyle” is a fantasy. I don’t know any gay person who follows that. In every relationship that I have seen, there is cheating. So take the cheating out of the relationship. If you find it beneficial to you and your partners to have a closed relationship, then do that. But you shouldn’t keep someone else caged in marriage. If he meets and desires someone else, let him go. He was never yours anyway. I got married to receive the 1,000-plus benefits—financial and otherwise.

You worked on the original development team doing coding for Grindr, the gay dating app. You mention that folks thank you for that contribution to the gay community. What would you say to someone who counters that the app promotes hook-up culture and devalues face-to-face interactions?

Grindr made connecting with other gay men easier [and more normal]. It does facilitate the hook-up culture, but it does not devaluate face-to-face interaction. With these apps, you meet new people, which would have been impossible otherwise. Those who don’t want them are free to avoid the apps.

Your therapist noted that you thrive when you have a challenge. For example, you took up painting at his suggestion, even when you had to use your nondominant hand because of the stroke. What’s the next project?

Dealing with the aftereffects of a stroke takes up my time. But painting gave some meaning to life. Meanwhile, since the stroke, [my husband and I] have become world travelers. And I’m thinking of writing a new book.

Any last words of advice?

Don’t let your HIV status get in the way of what you want to do. Being HIV positive is just a thing that you deal with, like many conditions other people deal with. Don’t dwell on it. Maybe a gay crow attitude will help you.

Comments

Comments