A set of mutations to a person’s genes predicted how completely their immune system recovered after starting antiretroviral therapy, say the authors of a study to be published in a forthcoming issue of Nature Medicine and reported by Newswise.

Though the majority of people who take combination antiretroviral treatment have a favorable response, with HIV levels being reduced to undetectable and CD4 counts significantly elevated, some people fail to have a robust recovery of their CD4 cells despite keeping virus under control. Various theories have been proposed to explain this discordant response, but none have thus far been proven.

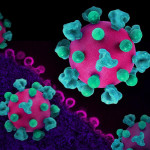

In a 2005 study, Sunil Ahuja, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and his colleagues found that people with specific mutations to the genes responsible for the creation of a CD4 cell receptor known as CCR5, and a related protein called CCL3L1, which binds to the CCR5 receptor, have faster disease progression before starting antiretroviral therapy. Ahuja’s team wondered whether the genetic mutations that were associated with faster disease progression may also be responsible for a less favorable CD4 response to antiretroviral therapy.

Ahuja’s group separated a cohort of people living with HIV—who were being treated at Wilford Hall Medical Center in San Antonio and had started antiretroviral therapy—into three groups: One group was made up of those with the genetic mutation that was associated with the fastest HIV disease progression, called high risk; another group had genes associated with the slowest disease progression, called low risk; and a third group had a mix of genes, called moderate risk.

The researchers found that on average those in the low-risk group had significant increases in CD4 counts that continued to rise over a period of years. Conversely, those in the high-risk group had an initial CD4 increase over the first two years of treatment but then began to have declines.

Prominent HIV researcher Mike McCune, of the University of California, San Francisco, on learning of the study results summed up their importance, saying, “By showing that the same genetic makeup increases susceptibility to immune depletion and impaired immune recovery, the authors provide novel tools that may allow us to predict both those who will progress faster after HIV infection as well as those who might benefit from earlier initiation of [antiretroviral therapy].”

Genes Predict Immune Response to Antiretroviral Treatment

Comments

Comments