They play with us when we’re well and comfort us when we’re sick. They stand by us through treatment failures, bad relationships and worse hairdos (unless they’re secretly searching the want ads when we leave the house). While we throw tantrums and shed tears, they just throw up and shed. At last, HIVers pay tribute to our better halves—the canine and feline (and equine and avian) pals that save our lives every day. And in a Paws, er, POZ exclusive, those selfsame furry friends answer the burning question: Is it really love? Or do you just stick around for the treats?

STICKING AROUND

Kevin Bently loved and lost Jack and Richard before he found Paul—but through it all, Henry was there to chew up the scenery. A tale of true love among four dudes and a dachshund

Dog Years: Henry (from left) with the author and Jack Sigesmund, 1987; with Richard Hackney, 1989; with Paul Grippardi and author, 2003Kevin Bentley

While I was growing up in West Texas, our pets tended to disappear when they became inconvenient: Fritz, the dachshund who destroyed our wading pool, was gone when my brother and I got home from school one day; Puddles, the little black spaniel who threw up repeatedly on a cross-country car trip, my father simply put out of the car at a rest stop. I thought of these disposals some years later, in 1986, when my mother first learned that Jack, the lover with whom I’d been living in San Francisco, had been diagnosed with PCP. “Get out of there before you get it too,” she told me flatly.

But of course I already had it—that is, Jack and I were both already HIV positive before we met one Sunday afternoon at the Giraffe Bar on Polk Street and moved in together a month later—only I wasn’t sick. (And I wouldn’t get sick. I am, I would come to learn, what’s now called a long-term nonprogressor.) Two years later, when Jack came home from his second hospitalization, we decided to get a puppy. Jack, formerly a gregarious maitre d’, was 10 years older than I and had very much been the dominant personality—but illness had blurred all that. “We’ll get a puppy, and we’ll name him Henry,” he said simply. Who was making this decision? I hadn’t had a pet in the 10 years since I’d left home; dog ownership seemed to mean accepting a certain amount of responsibility—no staying out all night or lying abed all day hungover. Getting a dog now seemed like an investment in living, a vote of confidence in our future, whatever its duration: We’re here now and we should be as happy as we can. “And,” Jack said, “when I die, you’ll have Henry.”

So we had the name but not the dog. Henry finally came, in a roundabout way, through PAWS, the group that helps both to care and find new homes for patients’ pets: A friend attending one of its benefits happened to hear about a couple in Sacramento who’d found a miniature dachshund puppy abandoned in a park, and several phone calls later our friend Bob was driving me to Sacramento to pick it up. (“I thought you might need these,” he said, popping open the glove compartment and handing me two tiny pairs of handcuffs.) When we pulled up to the little stucco house, three dogs shot out of a swinging dog door—the last, and smallest, hurtling himself at my head as I crouched in the grass. He seemed to know this was his big break. Back at the apartment, the little dog dove onto the bed and woke Jack, licking his face. See, Jack’s weary eyes said. Wasn’t I right?

Our yappy little red dachshund, whose sole concession to discipline was his becoming speedily housebroken, grew closest to Jack because he was with him all day long, curling up next to his head on the pillow. Henry amused and comforted Jack, but he also tromped across his KS-riddled stomach and tried to lap up the urine when the urine bag came loose from the hospital bed. He barked at the doctor, the ambulance crews and, several months after his arrival, the men from Daphne Mortuary who came to take away Jack’s body. He licked my tears when I wept, but he also chewed up my sunglasses and inhaled a breakfast muffin when I turned away to answer the latest sympathy call (and threw it up again perfectly whole when I yelled). He was, at all times, a dog.

I saw the terror in his grief, and mine; Jack had exited abruptly—would I be next? He howled when I went out, strewed the trash and slept on any article of my clothing within reach.

Henry was 3 by the time I met Richard, who had come along one night with Bob for our weekly racquetball game. As shy and solemn as Jack was extroverted, Richard owned a bookstore and two cats (one of several reasons we never merged households). There was initially some question of whom Richard was most smitten with, me or Henry. After the first night Richard spent with me, I came home from an errand to find a bag of gift-wrapped dog treats and flea powder with a vintage dachshund postcard addressed to Henry hanging on my door. Later on, if I was impatient with Henry for barking at passersby or taking too long to pee on a walk, Richard would chide: “Don’t you know how much that little dog loves you?”

In a video we made one Christmas, Richard sits in an armchair cradling Henry like a baby and crooning, trying to get Henry to sing, his party trick. Henry stares up in adoration, wags the tip of his tail, licks Richard’s nose, but won’t howl. “Well, Henry’s refusing to cooperate,” Richard says, laughing. “We’ll just have to send him to obedience school—where they’ll make him sing.”

After Richard’s death in 1992, it was just us again: I saw my own reduced emotional circumstances mirrored in Henry, who, stunned, graying, seemed to have accepted that happiness came only in two- or three-year allotments. At first his health suffered—there was serious back trouble (a common problem with wiener dogs) and an infection from which he almost expired. But he recovered, and we tended to each other over the lean years until I met and eventually moved in with Paul, situating us—between the loft and the shared house in the country—in high cotton.

Paul, who is HIV negative, found me through the relationship ad I’d placed, in which I billed myself a “long-term non-progressor.” He had no idea what that actually meant until halfway through our first long phone conversation. Yet he didn’t discard me.

Recently, when I picked Henry up at the vet after leaving him overnight for blood tests, the young woman in a green lab coat who carried him out said, “Henry’s been a perfect gentleman.” “You haven’t slept with him,” I told her. He’s 112 in dog years now, and, as befits a centenarian, he farts, hogs the covers and sneezes copiously.

The puppy that leapt across the bed to lick Jack’s face has grown, filled out and now shrunk to sinew and bone at age 16. His face and legs are white, his eyes murky and opaque with cataracts, a benign swelling alongside one ear like Billie’s gardenia. He sleeps with his tongue poking out of his mouth and can’t hear the front door opening anymore. He retains the knack for ripping open wrapped packages with his few remaining teeth, regardless of whether or not they’re meant for him. He has never, to my knowledge, obeyed a command or slept in a dog bed. Not long ago, we finally covered the loft’s cement floors with linoleum and carpet. “Honey,” a friend pointed out as Henry coughed up his heartworm medicine, “usually people get the new carpet after the old dog dies.”

Watching Henry thin and whiten, I’ve come slowly to the realization that, contrary to expectations, I’m going to be the one left to turn out the light. With Jack and Richard both, there were times when, hurrying home after work and looking up at the lit window, I’d think, He’s there waiting for me, but one day he won’t be—and I’d rush in and grab my lover in my arms till he’d laugh and push me off, saying, “I’m not going anywhere.” I remember that feeling now as I watch Henry sleeping, which he does most of the time.

Unlike people, who necessarily tire of discussing the dead, Henry’s connection to those we love stays constant. He whimpers and his back legs twitch, and I imagine Jack and Richard moving as unremarkably through his dreams as they do mine.

Bilingual Bow-Wow: Jairo Norena and Chocolate, Queens, New York

DOS AMIGOS

Not everyone finds his best friend on death row, but Chocolate, Jairo Noreña’s cocker spaniel/Doberman mix, was lucky to do just that. “My friend Zaida was unable to keep Chocolate because her new building doesn’t allow pets,” says Noreña, a Colombian who’s been living in the New York City borough of Queens since 1991. “She’d taken him to an animal shelter, and they were going to put him to sleep, so I decided to take him.”

Since that fateful rescue three and a half years ago, Noreña and Chocolate have discovered they’ve got a lot in common. Both are “nervous and very quiet,” according to Noreña. And both know some English and a lot of Spanish. “He understands words in both languages,” Noreña says proudly. Plus, Chocolate’s the ideal roommate: “He’s so obedient and clean. When I’m eating he never asks for anything. And when we go out for walks, he never barks at the other perritos.”

Noreña, for his part, adores Chocolate’s company. “Having HIV is something that constantly gives you surprises,” notes Noreña, who tested positive in 1989. “Chocolate is always there for me.”

OUR BUDDIES, OURSELVES

How can HIVers with pets stay safe and healthy themselves? Cal Cohen, MD, busy caring for Boston HIVers, had his chow/retriever mix Murphy and lab Ceili phone in these tips:

- Talking toxo: HIVers and neggies alike can be exposed to toxoplasmosis parasites in kitty poo—but that won’t put you at risk for brain-addling toxo illness unless your T cells drop dangerously below 100. If they do, must Kitty go? Nah. If you’ve long owned a cat, you may well have been exposed to toxo already; Doc can test you. If you’re toxo-negative, have the vet test Kitty for it—and if Kitty’s negative, keep Kitty indoors and on commercial cat food only. If Kitty’s positive, try to guilt-trip a friend into cleaning and changing the litter. And if your Ts are that low, hopefully Doc’s got you on PCP-preventing Bactrim, which wards off toxo illness, too.

- More feline advice: Wear latex gloves while handling the litter, then wash up right after. Keep Puss indoors. Talk to your vet about having Puss’s nails removed or clipped to avoid scratches, which can cause serious infections in anyone, HIV or no. If Puss swipes ya, wash the scratch and call Doc if you notice fever, redness, swelling or swollen lymph nodes.

- And the rest of them critters? Visit www.sonic.net/~pals/ safe/safe_pet.html. Otherwise it’s all common sense: Feed your furry friends only commercial or well-cooked food (raw meat can give ‘em parasites). Keep ’em flea-free and frisky with vaccinations and routine checkups. Does Fido or Fifi have diarrhea? Avoid touching it—and have the vet check pronto for parasites. Got a Tweety? Wear latex gloves and mist the cage before cleaning it. Avoid strays of all kinds. And if your pet is bigger than you, it had better be dumber. Meow.

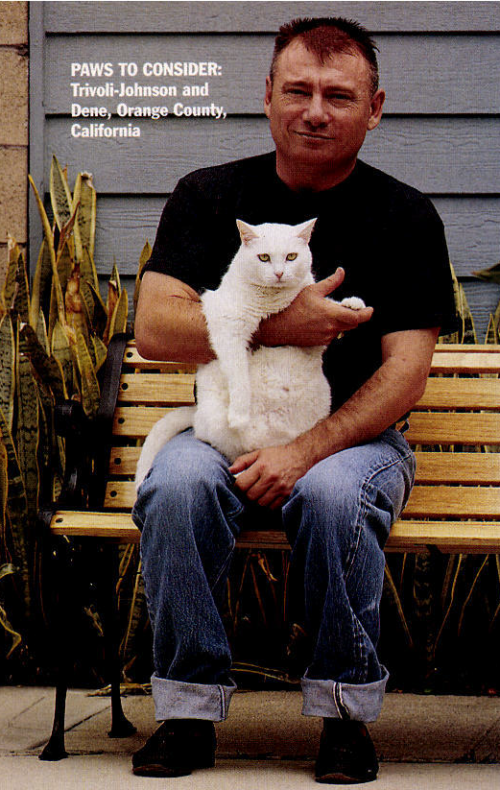

Paws to Consider: Trivoli-Johnson and Dene, Orange County, California

THE CAT WHISPERER

Stephen Trivoli-Johnson’s friend Lynden, who’s also HIV positive, had gone for a walk. “He came into the house and said, ‘Come see this,’” recalls Trivoli-Johnson, a former bank auditor from Orange County, California. Left for dead under a nearby bush was a tiny white kitten covered in dirt. “It broke my heart,” recalls Trivoli-Johnson, who, despite warnings that cats can infect PWAs with toxoplasmosis (See “Our Buddies, Ourselves,”), took the kitten home.

A quick meal of the nutritional supplement Ensure perked the kitten right up. Trivoli-Johnson, who lives on disability, christened her Dene, a Navajo name meaning chosen, and the two became fast friends. That’s been important to Trivoli-Johnson, 46, who has lost almost all his friends to AIDS since testing positive 19 years ago.

In their four years together, the cat has provided some much-needed comic relief. “One morning I was feeling real blue,” Trivoli-Johnson remembers. “I looked over from the bed and saw Dene and this baby bird”—which had somehow gotten in the house—“staring at each other. When I got up, the bird was chasing the cat!”

About a year ago, Trivoli-Johnson and Dene welcomed another abandoned cat, KeeKee, into their home. (This one was named by Trivoli-Johnson’s 3-year-old niece, who couldn’t quite pronounce kitten.) “The cats always make me feel wanted,” Trivoli-Johnson explains. “Even though I have wonderful family and wonderful support, there’s some things I can’t tell them. I tell the cats.”

E-mail Stephen, Dene and KeeKee at stephen@ocapwa.org

THE RIGHT VET FOR YOUR PET

“Your bond with your pet is invaluable,” says Columbus, Ohio, veterinarian Jennifer Jellison—and with three kids, five cats, three dogs, a rooster, snake and ferret, she’s got plenty of value herself. This year alone, she’s offered TLC and a lot more to the pets of about 50 HIVers, many referred by the Columbus AIDS Task Force. Jellison shared with POZ these tips for finding the purrrfect vet:

- Call your local AIDS service organization (ASO) to see if it can point you toan HIVer-friendly vet—perhaps one who cuts a discount to HIVers in need.

- Probe your pet-keeping pals for a fuzzy referral from someone you trust.

- Visit www.healthypet.com or call 303.986.2800 to find a clinic near you that’s been approved by the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA)—a good sign that it’s clean and courteous. Call and ask if they offer boarding and grooming, emergency services, payment plans and house calls.

- When you’re checking out vets, scan the facility—and bring Benji along (think of it as doggy daycare). Is it clean? Friendly? Beware clinics that bar tours.

- Get an estimate. Fido making seal sounds? Muffin puking bright blue goo? Head to your vet’s office and ask for an assessment of treatment costs. Too steep? Say so—and try to work out a compromise.

- Check around town for a vaccine clinic that does yearly preventatives like shots and heartworm tests cheap or free. Then you can save the vet for illnesses and emergencies.

Breeder of Champions: Greg Louganis, Malibu, California, with Gryff

BEST IN SHOW

It makes sense that someone used to the high dive—and high-level competition—isn’t content to laze around the house with his pooches, tossing them the occasional Milkbone or playing fetch in the backyard.

So it is that diver Greg Louganis, the four-time Olympic gold-medalist, has taken his three dogs to the peak of canine competition. Nipper, a six-year-old Jack Russell terrier, is in training for the American Kennel Club Nationals, one of dog-training’s most prestigious events. Likewise, Dobby, another Jack Russell, and Gryff, a Border collie, work out with—and against—champs. “Nipper is working at a pretty high level,” Louganis says. “She’s been to the Grand Prix, an agility event,” he notes in the language of dog-show insiders. “She’s up against some dogs on the U.S. World Team.”

As much as Louganis likes to discuss the technical aspects of dog training (“I’m looking into doing some go-to-ground work with Nipper”), his biggest connection to the dogs is emotional. “They keep me grounded,” he says. And they teach him to live better, too: “They’re much more forgiving than people are,” explains Louganis, who has co-authored the dog-care how-to For The Life of Your Dog, in addition to Breaking the Surface, his account of coming out amidst athletic fame as both gay and HIV positive. “If someone pisses me off, I’m like, ‘Grrr….’ I’ve learned from them how to let go a lot quicker. I’m a lot more forgiving because of them.”

PUP ‘N’ PUSS PAGES

Collar these top tomes on people and their pets:

The American Animal Hospital Association Encyclopedia of Dog Health and Care by Sally Brodwell and the AAHA (HarperCollins, 1996). A mutt-have.

How to Be Your Dog’s Best Friend: The Classic Training Manual for Dog Owners (Little, Brown, 2002) and other books by Monks of New Skete. When it comes to canine wisdom, these upstate New York monks lead the pack.

The Cornell Book of Cats: A Comprehensive and Authoritative Medical Reference for Every Cat and Kitten edited by Mordecai Siegal (Random House, 1997). Don’t raise Garfield without it.

The Healing Power of Pets: Harnessing the Amazing Ability of Pets to Make and Keep People Happy and Healthy by Dr. Marty Becker (Hyperion, 2003). Written proof of what you’ve known all along.

The Hidden Life of Dogs (Pocket, 1996) and other books by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas. What dogs do when we’re not around—and why. Fascinating.

Pack of Two: The Intricate Bond Between People and Dogs by Caroline Knapp (Delta, 1999). Deeply moving.

The Loss of a Pet by Wallace Sife (Wiley, 1998). Sife, who founded the Association for Pet Bereavement, honors this pain—and helps you through it.

Walter, the Farting Dog by William Kotzwinkle (North Atlantic, 2001). Yours does, too—admit it.

Angie Lawrence and Goldie, South Berwick, Maine

UNBRIDLED LOVE

I always liked horses—I rode them as a kid,” says Angie Lawrence, 41, of rural South Berwick, Maine. Still, by the time she was 35, her lifelong wish of owning one had been deferred: “I was diagnosed in ’93, pre-protease, and I was pretty focused on my disease.”

One day, a woman walked into her family’s swimming-pool business. As the two got talking, the woman revealed she’d just bought a horse. “I said, ‘Wow, I’ve always wanted one, but I’m too old,’” Lawrence recalls.

What she really meant was “the doctors had me scared that animals would get you sick,” Lawrence explains. Still, the woman told her, “Do it. It’s your dream.” Soon, Lawrence started hanging out at a nearby barn, where she met Goldie, a sweet-tempered 22-year-old quarter horse with a bad leg injury. The vet was thinking of putting her down. “We didn’t know if she was going to be whole or not,” Lawrence recalls. “But I didn’t know if I was going to be whole or not, so I thought, ‘Let me give this a shot.’”

Now she and partner Leigh Peake live on a farm with Goldie and three other horses. “We healed each other,” says Lawrence, who has never had any major HIV-related health problems but still found herself obsessed with the prospect. “Taking care of Goldie was a way of taking care of myself. It made me think, ‘Why was I focusing on my illness so much?’”

E-mail Angie and Goldie at angielawrence@comcast.net.

Fetching Profiles: Vanessa Olave and Max, Atlanta, Georgia

THE MAX FACTOR

When Vanessa Olave’s best friend, dog-breeder Stephen Brue, offered her a springer spaniel puppy a year ago, she had to think about it—hard.

The 45-year-old case manager at Our Common Cause, a substance-abuse treatment center for HIVers, wanted a dog. She’d grown up with dogs. But “people said I shouldn’t get one because of my HIV,” says Olave, who tested positive in ’89. Still, after praying and pondering on the matter, she decided to go for it.

Love at first bark ensued. “When I first saw him, he came running up to me,” says Olave of her tricolored Max. “He had hazel eyes, and I thought, ‘Gosh, me and this dog are going to have a good experience together.’ And that’s just what’s happened.”

Over the year, not-so-mad Max has taught Olave patience and responsibility. She’s taught him to sit and stay, even sans leash. Most important, Max is a good companion to Olave—and a link to best friend Brue, who died shortly after giving her the spaniel.

“I live by myself, and with Max, I’m not alone,” she says. “He brings me a lot of serenity and peace.”

E-mail Vanessa and Max at volave@bellsouth.net.

CREATURE COMFORTS

Check out these resources for HIVer-friendly pet help:

- The CDC’s Healthy Pets, Healthy People website (www.cdc.gov/ healthypets/index.htm) has a special English/Spanish HIVers’ section—with state-by-state links and phone numbers for Pets Are Wonderful Support (PAWS), Pets Are Loving Support (PALS) and other groups that help sick HIVers keep their pets.

- The American Veterinary Medical Association offers great info on pet health atwww.avma.org/careforanimals/default.asp

- Mourning a pet? Talking about it helps. Call the ASPCA’s Pet Loss Hotline at 800.946.4646, enter 140-7211, then your phone number (with area code), and a bereavement specialist will call you right back.

At His Service: Robert Jackson, Rusty (left), and Duke, Dallas, Texas

DOGS ON IT!

Robert Jackson’s service dog, Duke, is more than a buddy—he’s a Lassie-level lifesaver. Jackson, 50, a former movie projectionist from Dallas who tested positive in 1987, got the 80-pound, mixed-breed dog about five years ago, while suffering from HIV-related dementia. (He already had a pet dog, Rusty.) Duke was supposed to help him negotiate traffic and other daily routines.

But as combination therapy cleared Jackson’s dementia, Duke’s responsibilities increased: About 15 months ago, Jackson began having terrible seizures (his doctors think they’re HIV-related). Duke wasn’t trained to work specifically with epileptics, but Jackson says Duke can predict his seizures as much as an hour in advance—and alerts him by whining or pawing at him. That prompts Jackson to take his anti-convulsant medication. If the medication doesn’t work, Duke uses his immense weight to immobilize his owner. “He’ll physically lie across me,” Jackson marvels— and swears that 50-pound Rusty, also a mutt, has stepped up to assist Duke. Rusty now lies across Jackson’s lower body while Duke takes the chest.

Jackson says Duke has saved him in several dangerous situations, such as dragging him out of a crowded street when a seizure struck him unconscious. Now the two are taking on Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) for prohibiting Duke from its buses and light rail on grounds that it only allows service dogs for the blind. Jackson says he hopes his lawyer will soon reach a settlement with DART that will “stop discrimination against anyone who uses a service animal.” That, he beams, would be “a really important victory”—and Rusty and Duke, whom Jackson says he counts among his closest friends, will be there right beside him to share it. If, that is, they’re not on top of him.

CHARLOTTE’S WEBSITES

Sniff out these critter-cally acclaimed cyberspots:

- www.aspca.com The website of the venerable American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals will direct you to the pet of your dreams via animal shelters and SPCAs near you. There’s also pet-care tips galore and animal-rights news and campaign info.

- www.peta.org If the mainstream ASPCA is the amfAR of animal rights, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals is its ACT UP, with a string of controversial PR coups to its credit—like billboards imagining Christ as a vegetarian, or “prince of peas.” Its website posts what it deems animal abuses everywhere—and tells you whom to call to protest.

- www.pets-in-the-news.com Kitty survives Twin Towers disaster! Dog saves boy from rattlesnake! Real-life headlines both heroic and hokey, along with pets in fashion, politics, Hollywood and more.

- hometown.aol.com/prayersforpets/home.html Is your favorite furry friend ill? Tell the good folks here and they’ll pray for him or her. The site’s nonsectarian, but its “pet saint” is, of course, creature-lovin’ Francis of Assisi.

- www.thedogpark.com Find a dog park—plus endless other pet-related sites and services—in any city.

- www.funny-pets.com And they are. Yours, too, can spread the love and the laughs—just post a pic.

1 Comment

1 Comment