|

| David Hancock |

Back in 1996 or ’97, I was washing a big soapy bath of dirty dishes in the sink of a house I owned in Surfside, Florida. Beyond my kitchen window was a lush backyard of unmowed grass, a steel-pipe clothesline T and the huge trunk of an avocado tree I shared with a neighbor. Gator pears, we call them down South; the big green-skinned ones.

I was scrubbing a wine goblet and thinking of a guy I’d met, a handsome Tony-nominated actor who’d come through Miami in a road show of Angels in America. In the bar he told me he was poz; we later enjoyed a moonlit safer-sex quickie by a lifeguard stand on Miami Beach.

We’d exchanged a few letters after his tour continued on. I’d gotten one that morning, warm and funny like the man himself. Little Florida me and a Broadway actor. How glamorous was that? And I really liked him. But there was the HIV. Sure I could armor up for one-night stands. But was that something I was willing to get involved with on a more intimate level?

While I was asking myself that question, the delicate glass suddenly burst in my hand. And there it was, the blood. I couldn’t get past the blood. Goodbye actor.

***

|

True story.

Back in 2003 or so, I wrote a mystical whodunit about a guy who comes home at 3 a.m. and finds his cat dead in the center of his room. From the electrocuted look of the beast—puffed, singed hair and bared fangs—he perceives the cat has diverted a death spell meant for him. Cats will do that. Everyone talks of the loyalty of dogs. But a cat, if you’ve treated it well, will intercept the demon. Wrest the death away from its clawed hands and receive it into its own little body.

The protagonist spends the rest of the story trying to figure out who sent the death curse. Before they try again! I was well into subsequent rewrites before I realized the unconscious symbolism: HIV was the death spell. And I have spent years of casual sex wondering which one would be the demon who finally delivers the killing curse. That’s the thing about keeping a journal or doing creative writing. You may not win a prize or produce a bestseller. But you can learn some things about yourself that you didn’t know.

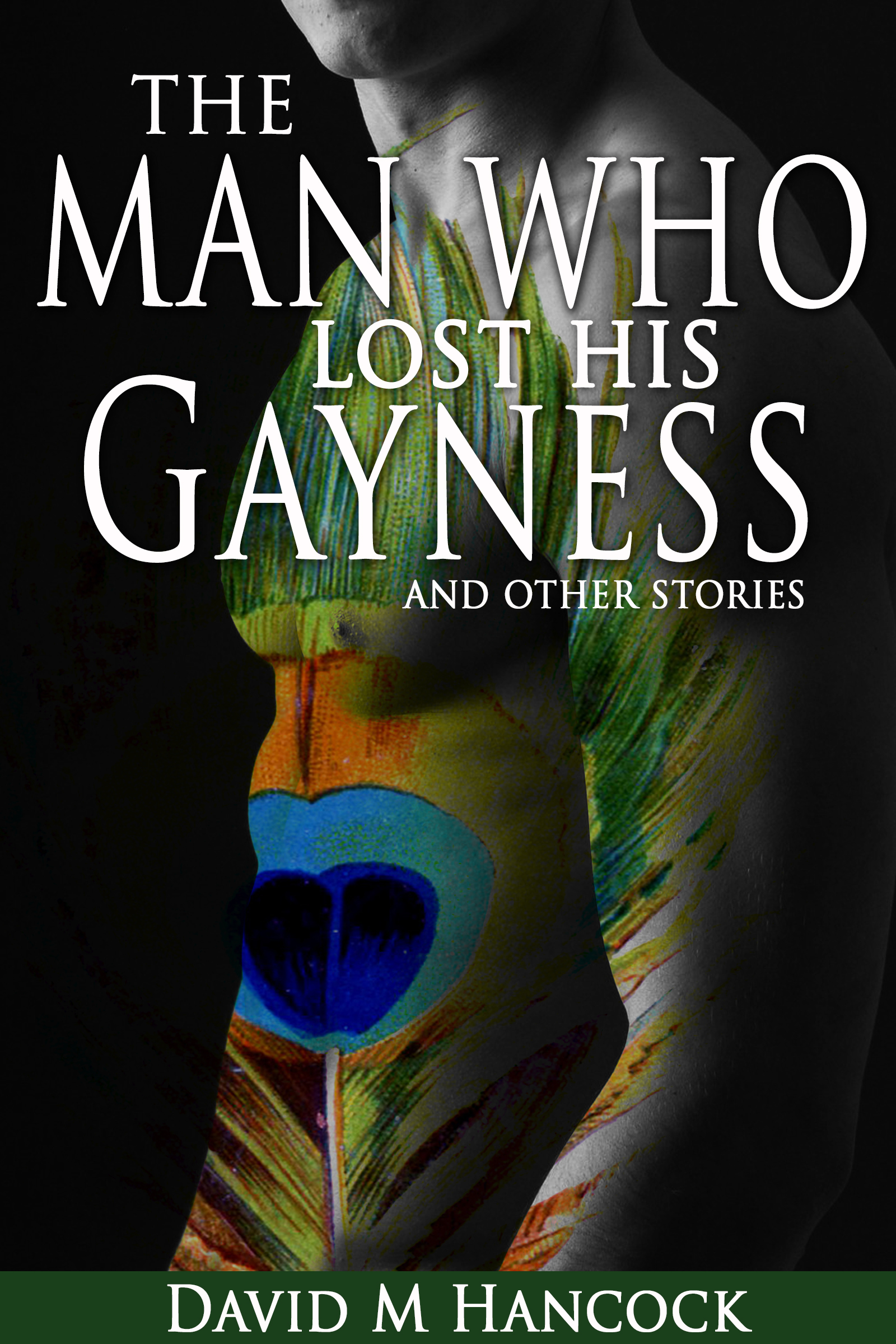

I recently gathered some of my short fiction in The Man Who Lost His Gayness. Looking at my work, I’m struck by how present HIV is in my stories. HIV has been a black raven perched on my left shoulder as I walk through life. HIV is the blurry monocle through which I examine a potential partner. My stories, cloaked in magic and metaphor, reflect my twisted relationship with HIV. Living 30 years under the shadow of HIV has done a number on my head—and I have a lot of deviant fiction to prove it.

One story in my collection has a special connection to POZ. "Far Away, And In Someone Else’s Ass" won first place in the POZ fiction contest in 2005. Back then it was titled "Rape Potion No. 9," which now seems to me a bit cheesy; you hear that ’60s pop song in your head, which is way too perky for the story. "Far Away" is a grim depiction of a gay rape; it encompasses all my fears about contracting HIV through the years.

The story has its origin in an article I’d read in The New York Times about an apparent "super bug" that went from seroconversion to AIDS in a year. I remember thinking: "That’s it ... I give up ... I throw in the towel." And all my fears and frustrations about living under a plague bubbled up into words.

A story I wrote in 2013, "I Don’t Know Why," describes a safer-sex glitch that happened to me in real life. Without going into too much detail, it involved blood and saliva. It was a reminder that even with the best intentions ... shit happens. I like this story because even as the protagonist considers whether transmission has occurred, he’s already planning his medical strategy.

Those two stories reflect an evolution in my attitude to HIV as I’ve gotten older. "Far Away" represents all the scary years of the 1980s and ’90s, when you literally took your life into your hands when you hooked up. And no one could give you a definitive answer about what was safe to do—particularly about the risks of oral sex. The second story is calmer. It reflects the knowledge that even if I finally contracted HIV, I would have a lot of medical options and many good years ahead of me.

***

I recently had an epiphany about how I think about HIV-positive folks. In 2012, I was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. I now have a lifestyle that includes pills and bloodwork, sporadic gastro distress and hours spent in medical offices. I have a chronic lifetime enemy trying to break down my body; but I also have powerful tools to fight back.

And it struck me: this is what HIV would be like, if I finally got it. Meds and tests and doctor’s visits. Poz and Type 2: We’re going through a similar thing; facing a manageable condition with lots of medical options. You wouldn’t wish either malady on anyone. But both are doable. With a little effort you can have many, many good years. It’s not so scary.

I had another revelation in May, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a formal recommendation for using the HIV drug Truvada as a preventative measure against transmission. I read any story about HIV that I come across; but I hadn’t seen this development, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), working its way up the medical establishment.

I see it mentioned now in online profiles: PrEPed and ready for action. I interpret this to mean the dude wants to have unsafe sex. At this stage of the game, I’m not ditching my condoms and I don’t care what anyone is promising. But the idea that you could have a poz partner, practice safer sex and also take the drug as extra security has wormed its way into my mind. It seems like an acceptable risk. It cuts to the heart of my own hesitation.

In casual hookups, I assume everyone is poz and conduct myself accordingly. I don’t even ask. But the idea of having HIV in your bed every morning ... that’s where it gets dicier. Sleepy morning tumbles when your guard is down and other domestic slipups. The daily question mark of living with a partner’s HIV is too scary for many people; they would rather not engage. You see it all the time: DDF (drug and disease free) for same, neg for neg. Poz dudes seem to never make it out of the gate as boyfriend material.

Maybe Truvada changes that. Imagine a world where people who need the meds are taking them, and keeping their viral counts low. And their neg partners, if they’re worried about it, are also taking the pill for peace of mind. And anyone else who thinks they need it also takes the pill. And we can all just relax and be nice to each other.

***

One thing more. True story.

Back in 2001 or ’02, I met a guy in New York City at a bar in Chelsea. His name was Guillermo and he was a sexy little beast. I wasn’t smitten, but we had some fun. Skating on the river, phone conversations; more than just hooking up. Two weeks after we met he called me on the phone and said, "Look, I have to tell you something.’’ I listened and then assured him it was not a problem. And then I never spoke to him again.

To Guillermo and other poz dudes: I’m really sorry for the shitty way I’ve treated you through the years. The way I coldfished you after you put your cards on the table. Or worse, the phony way I pretended it was no big deal—and then dropped you cold. No returned calls, no answered emails. Or how I’ve sped past your online profiles when I saw the "+" sign. Next!

I wouldn’t open my heart for you, even a little. I was too scared. And then it just became an engrained habit to excise you. In 2014, I want to free my mind. I want to shake off knee-jerk behaviors that are rooted in decades-old fears. I want to include, not exclude. I’m tired of living in fear of HIV. In the immortal words of Barbra and Donna: Enough is enough.

David M. Hancock is a long-time homepage editor for CBSNews.com in New York City. He has worked on the Web since 1995. Before that he was a reporter for The Miami Herald and several Texas newspapers. He is the author of The Man Who Lost His Gayness, a collection of gay-themed speculative fiction, available on Amazon.com.

19 Comments

19 Comments