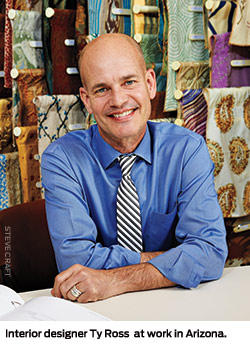

Ty Ross Goldwater is an interior designer and the HIV-positive gay grandson of Barry Goldwater, a.k.a. “Mr. Conservative.” A native of Arizona, his grandfather served the state and our country as a United States Air Force general, as a five-term U.S. senator and as the 1964 Republican presidential nominee.

Ty Ross Goldwater is an interior designer and the HIV-positive gay grandson of Barry Goldwater, a.k.a. “Mr. Conservative.” A native of Arizona, his grandfather served the state and our country as a United States Air Force general, as a five-term U.S. senator and as the 1964 Republican presidential nominee.

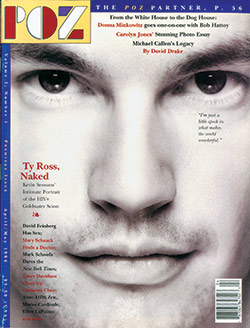

Ross also holds the distinction of being the first face on a POZ cover. His friend celebrity photographer Greg Gorman first asked Ross, who already was out as HIV positive, if he would talk. Gorman then shot the cover and the accompanying images. Kevin Sessums, known at the time for his Vanity Fair celebrity interviews and his long stint at Interview magazine, wrote the 1994 cover story.

The first-person narrative—which takes place in Los Angeles, where Ross was living at the time—caused a stir. (Search “Ty Ross Comes Clean” on poz.com for the juicy details.) Spoiler alert: Sessums and Ross hook up. We pick up the rest of the story from there.

So, the hook up…

Yes, Kevin Sessums and I hooked up. When you’re gay and single, you don’t put some chastity belt on. You’re a man, and that’s kind of how things happen. People get a little shocked by that.

Hooking up with me was not necessarily him doing me a favor, like “Look at me, I’m having sex with a positive person.” However, I felt he hooked up with me to make the story more salacious. I was a little irritated by that.

He did read me the article before it was published. I had said it was OK because I didn’t want to say to him, “Hey, maybe don’t put that hook-up stuff in.” It was a distraction to the narrative, which was already interesting.

The POZ article reached the Vanity Fair crowd, people with HIV/AIDS and the general public. There were some in the conservative media saying things like, “Look at him, he’s such a slut.” But since then, the article really hasn’t followed me.

Why do you think that is—your family, your personality or something else?

I’m shy and not a real public person, although I was always hoping that I could use my family name to advance gay rights.

I live in Arizona, a very conservative state, and a lot of my clients are Republicans, so I have to hold back when I’m talking politics.

The first thing that comes up is whether I’m a Republican like my grandfather. I have to say, “No, I’m exactly the opposite. I’m a bleeding-heart liberal.” And sometimes with clients that doesn’t go over well.

I’ve experienced blowback, so I’ve learned to shut my mouth with people.

Let’s talk about your grandfather. What was it like coming out to him as gay and as HIV positive?

I had never been in the closet. My grandmother knew I was gay since I was a kid. She’d say, “Isn’t he a special kind of guy?”

My grandfather knew I was gay since I was a teen. He was fine with it, and it was never an issue. He wasn’t terribly religious. It was all kind of a non-issue in the family.

In the early 1990s, I went to go protest in support of a local ordinance to include sexual orientation and gender identity into the city charter, and there was this raucous debate.

My grandfather happened to be at our house when I got back. “I heard you went downtown. Good job, standing up for what you believe in,” he said.

He was aware I was in POZ. I was never dealt any shame about it or met with adulation. It was neither, which was good for me because I didn’t have to feel any guilt.

We never really talked about me being HIV positive. Without a doubt, he knew I was positive and was supportive of me more in that I was involving myself in standing up for gay rights.  Tell us more about your HIV diagnosis.

Tell us more about your HIV diagnosis.

I found out in 1989 from a doctor in Los Angeles who suggested I get tested. I sort of assumed that I was positive, just based on all the sex I had during the ‘80s. Some of it was protected, and some of it wasn’t.

A nurse told me over the phone. They didn’t even call me into the office to say, “Oh, I’m sorry, you’re positive.” Nowadays, they explain things and tell you how to move forward.

There was no HIV drug on the market yet except for AZT. I didn’t want to deal with it, but I went back to the doctor to get my T cells checked. The viral load test wasn’t available at that time. My T cells ended up being 700, which made me feel a little relieved.

I knew I had a little time left, but at the same time it was a death sentence. In the back of my mind, I was thinking in the next four or five years I’m going to die. I moved back to Arizona in 1991 to be near my family and to try living a stress-free life.

After decades of living with HIV, how is your health today?

I’m a long-term nonprogressor, so I don’t take any HIV treatment. My viral load is undetectable naturally. I didn’t know that until the mid ‘90s when I was viral load tested. However, last summer I was diagnosed with prostate cancer, and now I’ve got the double whammy going on.

I had changed my general practitioner because my health insurance changed slightly. My new general practitioner went a bit deeper with a stress test for my heart and a prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test.

My PSA level came out elevated. It was 5.0. When I got tested again it was 4.9, so it hadn’t moved much. Then I went in for a biopsy and they found cancer cells. My goal in life now is to keep tumors from forming.

Tumors form inside your prostate and then move to the edge of your prostate. From there, the tumors can metastasize in your body and create problems. If I can keep them from forming by way of diet and exercise, then I can postpone treatment for as long as possible.

Having already survived HIV, I thought I was set, but now cancer has given me a new reason to watch what I eat. Last summer, I stopped eating red meat and pork.

Now I have mainly vegetables, limit animal protein to organic chicken and fish, and limit sugar and dairy. I don’t deny myself necessarily, but I try my hardest to eat healthy.

Given your current health, how does it feel to be a long-term HIV survivor?

I have horrible survivor’s guilt, because I don’t think anybody should’ve died. It’s just unfortunate that so many people had a slightly weaker immune system that couldn’t fight HIV off.

When I was single it was terrible. Everybody I met just didn’t get it. People just don’t understand HIV. They don’t understand that it’s pretty difficult to catch. It’s not just something that you catch capriciously.

People just don’t understand that. They hear “HIV” in their heads, and they see images of people dying, and they don’t want to have anything to do with you, which is tough. Fortunately, I have a partner who is understanding and educated.

We’ve been together eight years. Since he’s also HIV positive, it works because we’re on the same page. I can’t imagine what it would be like to be positive and single again.

Survival by Design

The first POZ cover guy reflects on the aftermath of his revealing 1994 interview and his life today.

2 Comments

2 Comments