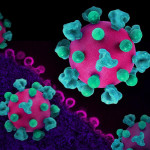

Using gene therapy to enhance the body’s ability to reverse chronic diseases has long been an exciting area of research. But it remains a controversial treatment approach, on account of major setbacks in clinical trials, including the deaths of some study participants. However, a recent article published in the San Francisco Chronicle suggests that, for one HIV-positive person participating in a gene therapy study, progress may be at hand.

For the treatment of HIV, researchers are hoping that they can use gene therapy to alter the structure of T4 cells – the prime targets of HIV – to either prevent them from becoming infected with HIV or to aid them in fighting off the infection.

In the study reviewed in the Chronicle, T4 cells are being programmed to produce ribozymes, enzymes that can shred two HIV genes: tat and rev. Without these crucial genes, HIV is unable to replicate.

Because T4 cells do not contain ribozymes, the researchers are hoping to plug these cells with the genetic material needed to “turn on” the production of this enzyme.

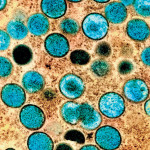

To do this, stem cells – “mother cells” in the body responsible for producing new T4 cells – are first removed from the blood. The genes are then inserted into the nucleus of these stem cells.

Genes require a vector if they are to effectively enter a cell’s nucleus and change its genetic makeup. Viruses are considered to be the vest vectors, given that they are so efficient at infecting cells and depositing genetic material. The vector used in the HIV ribozyme study is a mouse virus that can infect the cells and unload its genetic cargo. The mouse virus has been modified so that it does not cause damage to the cell or cause disease.

Once the genetic material has been incorporated, the stem cells are infused back into the patient. From there, the stem cells can create new T4 cells that contain the ribozyme needed to halt HIV from reproducing.

Gene therapy for other diseases suffered a major setback in 1999, with the death of an 18-year-old named Jesse Gelsinger. Mr. Gelsinger was participating in a gene therapy trial for ornithine transcarboxylase deficiency (OTCD), a genetic liver disease that causes poisonous levels of ammonia to accumulate in the body. He died four days after starting the treatment.

Approximately three years later, two infants involved in a French gene therapy trial for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency disease (X-SCID) – “bubble baby syndrome” – developed leukemia. Subsequent investigations by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration revealed at least six other deaths in clinical trials of gene therapy.

Today, gene therapy studies are closely regulated and watched by health authorities. The vector viruses used in earlier studies were concluded to be the cause of the most significant adverse events.

The Chronicle article reviews the experience of Michael DeLane, 41, a participant in a 74-person HIV ribozyme gene therapy study. Mr. DeLane, who enrolled in the study at Stanford University, says he does not know for certain whether he was among the half who received gene therapy or placebo (stem cells that have not been genetically modified). However, he does know that approximately a year after stopping his anti-HIV drug regimen, his viral load remains undetectable and his T4 cell count has more than doubled.

The Chronicle also reports that it has learned the Mr. DeLane is not the only participant in the study to maintain undetectable viral loads after stopping standard anti-HIV drug treatment.

As encouraging as this information is, it is important to note that data from the ribozyme study have not yet been reported and remain closely guarded by the researchers conducting the trial. In turn, it is impossible to conclude that Mr. DeLane’s experience is representative of other beneficial outcomes in the study.

Preliminary data, summarizing the effectiveness and safety of this particular gene therapy approach in all of the study participants, are not expected until February 2007.

Comments

Comments