Establishing a foundation to fund cutting-edge medical research was not a priority for Carol Gertz in the fall of 1988. Instead she was busy caring for her 22-year-old daughter, Alison, who had just been diagnosed with AIDS. Alison—known as Ali by her family and friends—had been at home with flu-like symptoms for over a week before her mother admitted her to a top-tier New York hospital. After a couple of weeks of nonstop tests, doctors reported they still had no answers. But there was one thing they hadn’t tested for: HIV.

An epidemiologist eventually spotted a shadow in Ali’s lung and identified it as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), the pneumonia associated with AIDS. She underwent a three-week recovery from pneumonia and eventually was able to return home. At that time, treatment options for HIV were extremely limited; the only available option was AZT, a medication with side effects that landed Ali back in the hospital two years later. Seeing how limited the development of drugs for HIV had been over the course of nearly a decade, Carol Gertz decided she needed to act. “We weren’t going to let Ali die,” she says.

In 1989, two close friends helped Carol Gertz start Concerned Parents for AIDS Research (CPFA), a nonprofit to fund better HIV treatments and to research how the disease progresses, with the hope of developing a cure. Initially supported by a circle of longtime friends, the network of fund-raisers soon expanded to include others whose lives had been upended by the virus—and those who realized that their children were also at risk.

One block away from the Gertz’s Upper East Side apartment, Eileen and Neil Mitzman were home tending to their daughter Marni, who had received an AIDS diagnosis a year after Ali. The Mitzmans had already lost their oldest daughter, Stacey, in a car accident in 1982.

Marni was 17 and a student at Bayside High School in Queens, when she began dating Bret, a boy who lived around the block. “He was an adorable kid,” Eileen Mitzman recalls. Bret was the only ex-boyfriend of Marni’s to test positive for HIV after she became sick.

With the ferocity of a lioness protecting her cub, Mitzman educated herself about her daughter’s diagnosis and became a relentless activist, drawing inspiration from organizers at ACT UP. She dove headlong into AIDS advocacy and fund-raising because after losing her first child, she was convinced she could save Marni’s life.

Mitzman teamed up with her friend Ivy Duneier to launch Mothers’ Voices, an advocacy group that lobbied Capitol Hill for increased HIV research funding and for more HIV prevention education in schools. In 1995, Mitzman introduced President Bill Clinton at the first-ever White House Conference on HIV.

“Everybody took this personally,” Neil Mitzman says about the work that he and wife were doing at the time. “It was almost like a vendetta,” he continues. “We were going to beat this thing, together.”

Eileen Mitzman was introduced to Carol Gertz when both women were caring for their sick daughters and advocating on their behalves. They would often attend each other’s fund-raising events and would pause on the street to talk, at times conveying solidarity only through the heaviness of a passing nod.

Gertz and Mitzman were not medical experts. Gertz was an affluent Upper East Side mom who ran a line of upscale clothing stores called Tennis Lady, and Mitzman had been a stay-at-home mother. Yet both became locked in a battle against a prevailing belief within the medical establishment and among the general public: Women and girls don’t get AIDS, especially not through heterosexual sex.

Nearly 10 years into the epidemic, Ali Gertz became one of the first American women to go public about her AIDS diagnosis. After she overcame the shock that she might die young, her initial thought was that she wanted to prevent other people from being in the same situation. Ali enlisted her mother’s help to raise awareness that HIV/AIDS can infect anybody, regardless of gender, sexuality, race or socioeconomic status. At Ali’s request, Gertz called up a reporter at The New York Times.

|

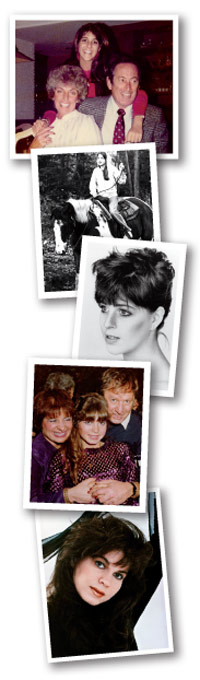

| From top: A snapshot of Carol, Ali and Jerrold Gertz in 1981; Marni Mitzman on horseback in the late 1970s; Ali in 1984; Eileen, Marni and Neil Mitzman at Marni’s sweet 16 party in 1981; Marni in 1986 |

Ali’s diagnosis sounded an alarm for parents who realized for the first time that their own children were at risk. “I want to talk to these kids who think they’re immortal,” Ali said in the Times interview. “I want to tell them: I’m heterosexual, and it took only one [unprotected sexual encounter] for me.” She traced back her HIV infection to a single romantic night she spent with a man when she was 16. The young man she’d slept with, she found out later, had died of AIDS during the years since they’d met.

The Times article was published in March of 1989, just as the founding women of CPFA were meeting in each other’s homes, around their kitchen tables, thinking of ways they could best help advance AIDS research. Eventually, the group decided to partner with amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, to help fund major AIDS research initiatives. Their next task was to raise money by throwing a party—and that was something these ladies certainly knew how to do. Their first fund-raising event was a gala held at the old Copacabana in Manhattan.

After the Times interview, Ali began touring schools and universities talking about safe sex. In every interview and at every speaking engagement, she spoke as a daughter and as a peer, breaking the barrier of denial that makes people think that AIDS can’t touch them. She never played down the fact that she came from a rich family, grew up on Park Avenue or that she had attended elite New York private schools. She would often talk about her dog, Sake, and her cat, Sambuca.

In a cover story for People magazine, Ali was illuminated as much by her lace and rose-chintz bedroom as she was by her natural physical beauty and poise. She was a young woman whose dreams of her future and promising career as an illustrator had been cut short. Ali stacked up all of her privileges, her serial monogamy and absence of injection drug use on one side and her AIDS diagnosis on the other, showing that it all equaled out to zero—no one could claim immunity from AIDS. For parents, her chilling message revealed their own vulnerability to HIV.

With friends and family by her bedside during her last months, Ali Gertz died in 1992 at the age of 26. “Even people in the government took note of the fact that this could have been their child, too,” her mom explains to POZ.

Today, Carol Gertz still makes an impression with her striking features and feathery, silver-blond hair. She has been carrying on Ali’s work for more than 20 years. She still sits on the board of CPFA and is also a board member of Love Heals, the Alison Gertz Foundation for AIDS Education, an HIV prevention nonprofit founded by three of Ali’s friends in the years after her death.

Though her daughter Marni died in 1991, Eileen Mitzman also continues to fight. She is now the board president of CPFA and often hosts monthly meetings in her well-decorated apartment on the Upper East Side. Feeling that she’d helped to change the national discourse on HIV/AIDS and had left her mark on Capitol Hill, Mitzman eventually left Mothers’ Voices and took Ivy Duneier with her. They both felt that the next step in their work was to continue funding breakthrough research projects as board members of CPFA.

Concerned Parents for AIDS Research has stayed true to its original goal of funding research, and it has raised a total of $7 million during the past 20 years. What’s perhaps more impressive is that the all-volunteer organization has achieved this with virtually no overhead. CPFA board members pay their own expenses, so every dollar that the organization raises goes straight to AIDS research.

Andy Lipschitz, MD, has been the medical director of CPFA since 1995, after the organization partnered with amfAR to fund the development of early protease inhibitors. He is among the group of dynamic CPFA board members who have helped shape the organization’s direction in recent years.

And it’s clear that he admires his fellow board members. “It’s totally from the goodness of their hearts that they are still fighting the disease,” he says about Mitzman and Gertz. “They’ve lost [one] battle, but they keep on fighting [the war]. We don’t have many people in the world like that.”

The CPFA board tasked Lipschitz with finding scientists who had innovative ideas in the field of HIV/AIDS research. They realized that CPFA could make the greatest difference by supporting individual scientists who were working on the development of basic research for treating and curing AIDS and by helping their research get National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding. Lipschitz set up a grant application process and brought the best of these proposals to the CPFA board to award one-year grants ranging from $50,000 to $250,000. These grants provide critical seed money to move research forward.

“We ask our researchers to answer a very specific question in a very short period of time,” says Lipschitz, explaining that the CPFA grants put pressure on researchers to focus on specific medical questions and prove a hypothesis. In case after case, proving or disproving these hypotheses has resulted in subsequent multi-million dollar NIH grants. In fact, the $7 million CPFA raised has garnered more than $40 million in NIH research grants, which Lipschitz sees as validation of CPFA’s direction.

Further making a case for a small organization like CPFA, Lipschitz explains that the nonprofit is free of bureaucratic red tape and is much more nimble than larger grant makers. “We can get from [discovering a researcher’s idea] to funding [it] in a matter of weeks to two months,” Lipschitz says. Clearly, CPFA has not lost the sense of urgency to advance HIV research.

“Our goal is also to be in tune with the specific secondary health problems of people living with HIV,” Lipschitz continues. CPFA concentrates research dollars on health issues that are causing early death in long-term survivors of HIV.

Putting the contribution of CPFA’s donors to work, from 2007 to 2009 the organization provided $250,000 in seed money to Mark H. Kaplan, MD, of the University of Michigan Medical School, to study the link between lymphoma and HIV. Kaplan investigated the role of human endogenous retroviruses in activating cancer.

“This topic is not esoteric, because endogenous retroviruses are probably the trigger of lymphoma, which affects many long-term survivors with HIV,” Lipschitz explains. After presenting his findings to an NIH panel, Kaplan received a $6.9 million grant to continue his groundbreaking research. For Lipschitz, this is only one of many breakthroughs to emerge from the organization’s funding of cutting-edge basic science. He’s already looking for the next scientist to fund.

In order to continue CPFA’s mission, Mitzman is adamant about engaging the next generation in their organization’s work. The board is currently searching for new energy outside of its current network of supporters.

It’s also searching for new energy on the inside: Ivy Duneier and many of the other board members have children in their 20s who are interested in getting involved in fund-raising. Like their parents, they have been affected by HIV/AIDS and understand the impact the epidemic has had around the world. As Duneier describes some of the elegant past gatherings and talks about an upcoming fund-raising event, she also notes: “It’s always been about more than just [throwing] a party.”

Mitzman describes CPFA as a boutique organization rather than a great big department store, like amfAR or the NIH. She explains that she doesn’t have enough money, enough power or enough influence to start a department store. “But [the world] needs both,” she says, finishing her thought before her husband can.

Mitzman’s right. After all, it’s the boutique stores that set the trends.

3 Comments

3 Comments