We can’t stop gazing at the young men Larry Stanton captured on paper in pencil and oil. The artist, who was known for his colorful portraits, died at age 37 of AIDS-related illness in 1984, early in the epidemic. Like Stanton, many of his subjects had escaped to 1970s Manhattan, where it was safe to be gay. Although many of them contracted HIV and died, their portraits remain and continue to inspire new generations—and new works of art, including a book of poems, a gallery show and an in-the-works documentary.

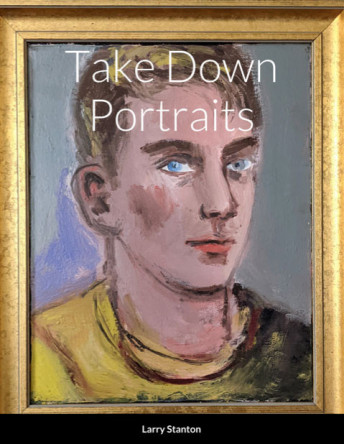

In Take Down Portraits: Drawings and Portraits by Larry Stanton, author Winthrop Smith writes a poem—what he calls a duet—for each Stanton portrait in his book, creating an imagined conversation or story to accompany each image.

The cover of Winthrop Smith’s book of poems inspired by Larry Stanton portraitsCourtesy of Chiron Review Press

Smith, who was honored in the 2018 POZ 100, which celebrated people 50 and over living with HIV and making a difference in the fight against the epidemic, tells POZ that he didn’t know Stanton personally. “I came out in the spring of 1984, the year that Larry died,” Smith says. “I don’t know that I ever saw him, but I passed the sign for one of his studios weekly as I walked to, or from, Julius’ [a famed West Village gay bar], where I was allowed to sit and write about what I saw at the bar.

To research his book of duets, Smith talked with people who knew Stanton, and he researched the time period and several of the men Stanton painted and drew. “Fortunately, many of his sitters wrote books or had books or had biographies, articles, blog pieces, written about them, and I used these sources to conjure the person who sat, or stood, in Larry’s studio.”

A “hybrid narrative/documentary” about Stanton titled Thunder Every Day is currently in preproduction. Directed by filmmaker Roland Tec (All the Rage, Pedal Uphill), the film promises an enticing look not just at Stanton’s life and work but at the culture and world around him, including Fire Island and New York City in the 1970s and early 1980s and his famous friends, such as artist David Hockney. Even more promising is the fact that the film includes Super 8 film Stanton himself shot. You can watch the promotional “sizzle reel” above; for more information, visit LarryStanton.net.

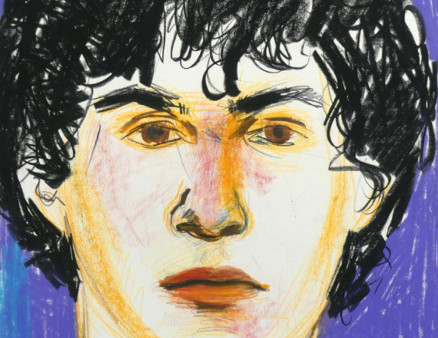

Finally, Stanton’s drawings are the subject of the new exhibition It Doesn’t Thunder Every Day, on view until July 1 at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in Manhattan. A sampling of the drawings appears in the slideshow below.

The exhibition features about 20 works on paper in colored pastel and pencil that offer a nice contrast to the larger oil paintings fans of the artist might be familiar with. For those not in the know, the art gallery provides a short bio of the artist:

Raised on a farm in New York’s Catskill Mountains before relocating to Manhattan, Larry Stanton (1947–1984) was encouraged to pursue his love of art from a young age. He studied at The Cooper Union on scholarship before dropping out after one semester to work at the mailroom of an advertising agency. Soon thereafter he quit, took a job at an ice cream parlor popular on the gay scene, came out, and quickly became the toast of New York, his beauty the stuff of legend.

In 1967, Stanton met Arthur Lambert, who was to become his partner and mentor, and enrolled in the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, CA, where he met lifelong friends David Hockney and Alice Sulit. While visiting Hockney in London during fall 1968, Stanton was introduced to Henry Geldzahler, then Curator of Contemporary Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. They forged a friendship that continued throughout Stanton’s life, with Geldzahler introducing him to leading artists including Ellsworth Kelly and Barnett Newman.

Upon his return to New York, Stanton received a scholarship to the New School, where he studied in drawing and printmaking. In January 1970, he had his first exhibition of drawings at Gotham Gallery. The following year he secured a studio in a basement space in the Village, where he could paint.

In 1976, Stanton’s mother was diagnosed with cancer; two years later she died. Her suffering caused him anguish, and he felt he didn’t live up to her expectation for him. The stress, combined with his excessive alcohol use, resulted in a psychotic episode that required hospitalization in November 1978. He quit drinking, fought to recover, and emerged with determination to realize his full potential as an artist.

In the following years, Stanton would create a series of portraits in charcoal, oil crayon, pencil, and pen, as well as paint, drawing friends, familial relations, and people he met while wandering the streets of New York. “It seemed as if he would draw anyone who would sit still long enough to be drawn, and when there was no one else around, he drew himself,” Lambert wrote in an essay published in Larry Stanton Painting and Drawing (Twelvetrees Press, 1986).

To learn more about Stanton and the new exhibition, POZ emailed New York gallery owner and director Daniel Cooney. Our exchange is lightly edited.

How would you describe Stanton’s style of portraiture? What makes him unique in this field?

I would say that he had an innate talent for tapping into a person’s psyche and personality. The portraits are very straightforward and incredibly revealing. I think one of the most compelling aspects of the work is the youthful vigor and naiveté of a young man just beginning his journey as an artist combined with the fact that it was actually the end of his life and the lives of many of his sitters—all young men.

View this post on Instagram

How does the collection of drawings at your gallery fit in with the rest of his work? For example, I’m more familiar with his large-scale oil paintings of men he knew.

Larry’s drawings tend to be primarily portraiture. They are usually of one subject and in color. There are a few full-figure and nude drawings, but mostly they are “busts.” His paintings are more varied. He created abstractions, some still-lifes and loose narratives with people in environments that are imagined.

View this post on Instagram

Stanton died of AIDS-related illness in 1984, during the early years of the epidemic. How would you say his work speaks to the AIDS crisis?

I think it’s quite a beautifully poetic body of work about the AIDS epidemic. The portraits are gay men living in the early days of the epidemic. Since Larry was highly productive for about five years leading up to his death, it is a very specific slice of time of a small group of people.

How has his reputation changed over the years, and what is it about his work and life that continues to draw our interest today?

The story of Art and AIDS is still being unpacked and examined. There is a lot of interest in the early days of the epidemic, but I’m not sure why exactly. In particular, I think his work is of interest because it isn’t specifically art about AIDS; instead, it’s art made in the time of AIDS by an artist who eventually died of AIDS-related illness. From all accounts, Larry had a lot of joy in his life but also a lot of challenges. I think it’s revealed in his work.

View this post on Instagram

Can you walk us through the history behind this show?

I have known about and admired Larry’s work for quite a long time. There were a few paintings offered at Swann Galleries Auction House last summer, and it reminded me of how much I really respond to the work. I then set out to track down the estate, which took a few months.

Tell us about the meaning behind the show’s title.

When Larry was dying, he wanted to leave his partner, Arthur Lambert, with a method of remembering him. Larry suggested that Arthur think of him when it thundered, a plan that didn’t pan out. Arthur wrote about it this way:

“For me, [Larry’s] death was a personal blow beyond the loss of an artist whose work I admired. For 18 years, he was the person I loved and my closest companion. One day in the hospital he tried to think of something which would cause me to remember him when he was gone and my memory of him had dimmed. After reflecting for a moment, he said, ‘I know, think of me when it thunders.” It sounded like a good idea, but it hasn’t worked out as we expected. It doesn’t thunder every day.”

Comments

Comments