Researchers have found evidence that a particular cancer drug can reactivate cells infected with HIV or SIV—HIV’s simian cousin—that are in a resting state.

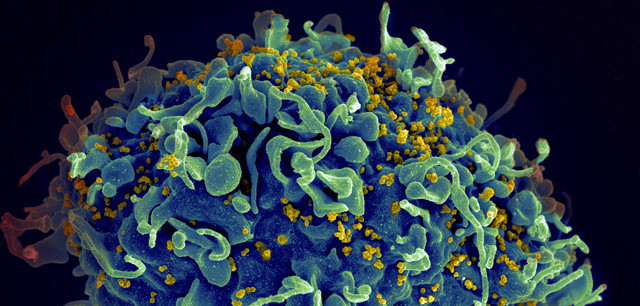

When HIV is fully suppressed by antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, a population of virus remains in what is known as the viral reservoir. The central component of the reservoir is HIV-infected cells that do not replicate. These latently infected cells remain under the radar of ARVs, which work only on cells that are actively creating new copies of HIV.

One of the various strategies researchers are investigating in the wide-ranging search for curative therapies for HIV is known as “shock and kill,” or “kick and kill.” In this approach, one or more agents cause cells latently infected with HIV to reactivate and produce new virus and one or more other treatments kill off those cells.

Publishing their findings in the journal Nature, a team of researchers conducted experiments in mice and monkeys treated with the compound AZD5582, which in other studies has proved safe as an experimental therapy for cancer.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the study was led by J. Victor Garcia, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Ann Chahroudi, MD, PhD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta; and Richard Dunham, PhD, of ViiV Healthcare and the UNC Chapel Hill.

First the researchers took 20 mice engineered to have human immune systems and infected them with HIV. Then they treated the rodents with ARVs. Next they injected AZD5582 into half the mice and a placebo into the other half.

Within 48 hours, the study authors detected high levels of HIV’s genetic material, RNA, in the blood of six of the 10 mice that received AZD5582. Levels of HIV RNA were up to 24-fold higher in resting immune cells in the bone marrow, thymic organoid (a mouse version of the thymus gland), lymph node, spleen, liver and lung of the AZD5582-treated mice compared with the control mice.

In other words, AZD5582 had indeed activated latently infected cells.

The treatment was not associated with toxicity, nor did it activate the mice’s immune systems.

In their next experiment, the investigators infected 21 rhesus macaque monkeys with SIV and treated them with ARVs. More than 12 months later, they gave 12 of the animals weekly intravenous infusions of AZD5582 for either three or 10 weeks.

Five (55%) out of the nine monkeys that received 10 doses of AZD5582 and none of the three monkeys that received just three doses experienced increased SIV in their blood. The levels of SIV RNA in the resting immune cells of the animals’ lymph nodes were significantly higher in those that received 10 doses of the treatment compared with the nine monkeys that did not receive AZD5582.

AZD5582 was safe for most of the monkeys.

There was no consistent reduction in the viral reservoir in the treated monkeys. This suggests that for AZD5582 to have a significant effect on the reservoir, it would need to be paired with another agent that could kill the activated reservoir cells.

To read a press release about the study, click here.

To read the study, click here.

Comments

Comments