On July 13, the World Health Organization (WHO) released two reports about aspartame, an artificial sweetener widely used in diet sodas, sugar-free chewing gum and other low-calorie products. (The most popular brand of artificial sweetener, Equal, contains aspartame and usually comes in blue packets, while Sweet ‘N Low, or saccharin, comes in pink, and Splenda, or sucralose, comes in yellow.)

The first report found that there is “limited evidence” that aspartame may cause liver cancer, leading the agency to classify it as a possibly carcinogen. The second report, however, says that the sweetener is generally safe at the quantities people typically consume.

“We’re not advising companies to withdraw products nor are we advising consumers to stop consuming altogether,” Francesco Branca, PhD, director of the WHO’s Department of Nutrition and Food Safety, said during a media briefing. “We’re just advising a bit of moderation.”

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which approved aspartame in 1974, issued a statement in response, saying it disagrees that research supports classifying aspartame as a possible carcinogen, given the shortcomings of existing studies. “Aspartame is one of the most studied food additives in the human food supply,” the agency wrote. “FDA scientists do not have safety concerns when aspartame is used under the approved conditions.”

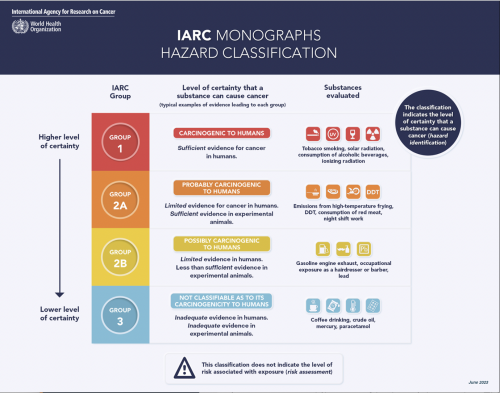

For the first report, from the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a working group of 25 scientists from 12 countries evaluated existing evidence about the cancer-causing potential of the sweeteners aspartame, isoeugenol and methyleugenol. The experts classified aspartame as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” based on limited evidence from human and animal studies and limited mechanistic evidence, meaning a known mechanism of action for causing cancer.

WHO

IARC classified aspartame as Group 2B, meaning it has a possible but unproven link to cancer. Many other common food ingredients, medications and environmental chemicals fall into the same “possibly carcinogenic” category. In contrast, processed meats, which have a clearer link to cancer, is classified as Group 1.

While IARC looks at the potential for harm based on scientific studies, the Joint United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) focuses on actual risks in the real world.

“JECFA also considered the evidence on cancer risk, in animal and human studies, and concluded that the evidence of an association between aspartame consumption and cancer in humans is not convincing,” said Moez Sanaa, DVM, PhD, of the WHO’s Standards and Scientific Advice on Food and Nutrition Unit. However, he added, better studies with longer follow-up are needed.

One problem with animal experiments is that researchers often feed the animals far more aspartame than a person would plausibly consume, even if they regularly drink a liter of Diet Coke or several cups of coffee sweetened with Equal a day. Likewise, earlier research found that rats fed large doses of saccharin were more likely to develop bladder cancer.

Experts recommended that people should not exceed 40 milligrams (JECFA limit) or 50 milligrams (FDA limit) of aspartame per kilogram of body weight per day. This means a person weighing 150 pounds would have to drink about a dozen cans of diet soda in a day. However, the risk of reaching an unsafe level may be higher for children due to their lower body weight.

What’s more, human observational studies that find an association between artificial sweetener consumption and various types of cancer do not show that the sweetener is the cause, because people who consume large amounts may have other contributing risk factors. (Click here for an artificial sweetener research review from STAT.)

The IARC report “is really more a call to the research community to try to better clarify and understand the carcinogenic hazard that may or may not be posed by aspartame consumption,” said IARC’s Mary Schubauer-Berigan, PhD.

While the chances of aspartame causing cancer may be minimal, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s beneficial. In May, the WHO advised that people should not use artificial sweeteners in an effort to lose weight, as there is no evidence that they reduce body fat, and long-term use may increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Comments

Comments