Last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released data showing that HIV incidence among Black folks had surpassed that of white folks since 1988. Now, new CDC data, released ahead of National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, describe some of the ways race, poverty, segregation and lack of infrastructure can interact to increase HIV risk in some Black communities more than others.

In other words, it’s systemic racism, HIV-related stigma and other barriers—not race itself—that leads to higher HIV rates among Black Americans.

“HIV disparities are not inevitable and can be addressed. The advanced, highly effective HIV prevention and treatment tools and COVID-19 vaccines that that have been accessed by some must be accessible to all,” Demetre Daskalakis, MD, MPH, head of the CDC’s HIV Prevention Program, said in a press release. “While there is no simple solution to equity, our nation must finally tear down the wall of factors—systemic racism, homophobia, transphobia, HIV-related stigma and other ingrained barriers—that still obstructs these tools against HIV and COVID-19 from equitably reaching the people who could benefit from them.”

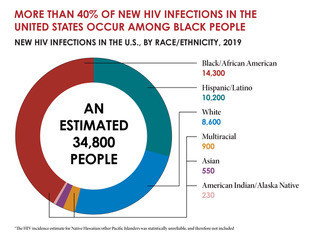

New HIV Infections in the U.S., by Race/Ethnicity, 2019CDC

According to CDC estimates, Black people account for more than 40% of new HIV cases despite making up about 13% of the United States population, and the annual diagnosis rate among Black folks was four times higher than the rate for all other racial and ethnic groups combined.

In 2018, a total of 13,807 Black people were diagnosed with HIV, according to data culled from the National HIV Surveillance System. Researchers overlaid that data, along with people’s addresses at the time of diagnosis, with the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index. The index looks at how equipped a given community is to respond to a public health crisis or natural disaster. Factors included in the index are poverty, lack of transportation and inadequate or overcrowded housing.

Of the 13,807 Black people with a new HIV diagnosis in 2018, three out of four of them lived in communities the CDC defined as either moderately or severely vulnerable, while just 8% came from communities with the highest level of resources. Specifically, 52% of Black people diagnosed with HIV came from the most socially vulnerable communities, and another quarter came from moderately socially vulnerable communities. In total, Black people in highly vulnerable neighborhoods, who face a high level of community stress, were 1.5 times more likely to acquire HIV than those living in the least vulnerable communities.

New HIV Infections by Race and Transmission Group, 2019CDC

What’s more, Black cisgender men living in high vulnerability areas were 1.6 times more likely to acquire HIV than their peers living in more highly resourced areas. Half of same-gender-loving men who acquired HIV in 2018 lived in communities of high social vulnerability, while just 8% lived in communities with the lowest social vulnerability.

Black men ages 45 to 54 were 2.3 times more likely to acquire HIV if they lived in the most socially vulnerable communities. Disparities were also seen based on the region where they lived. Men in the Northeast were most likely to have higher HIV rates in highest-vulnerability communities, with a 2.3 times increased risk for acquiring HIV.

Even more pronounced was the disparity of social vulnerability among Black men who were at risk for HIV through both sex with men and injection drug use. In this group, Black men were 11.6 times more likely to acquire HIV in highly socially vulnerable communities.

Viral Suppression in the U.S. by Race/Ethnicity, 2019 (45 Jurisdictions)CDC

Black cisgender women, meanwhile, had an even greater association between HIV diagnosis and the social vulnerability of the communities where they lived. Overall, women were 1.8 times more likely to acquire HIV if they lived in the highest-vulnerability areas. The disparity was most pronounced among women ages 35 to 44, who had a 2.4 times higher HIV rate if they lived in the highest-vulnerability areas, and women 18 to 24, who had twice the rate of HIV acquisition if they lived in the highest vulnerability communities. Again, women living in the Northeast saw the greatest disparity: They were 2.3 times more likely to acquire HIV than their peers in the most socially secure communities. In contrast, Black women in the Midwest were only 1.1 times more likely to acquire HIV if they lived in low-resourced communities.

The study didn’t include any data for transgender Black people.

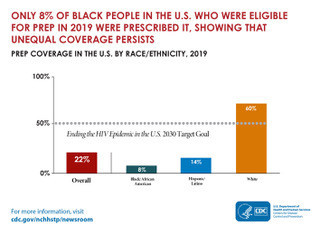

PrEP Coverage in the U.S. by Race/Ethnicity, 2019 Michael 2:43 PMCDC

“The social and economic marginalization of Black persons, including residential segregation, is correlated with factors associated with higher social vulnerability and higher rates of HIV diagnosis,” the study authors concluded. “Although social vulnerability does not explain all the disparity in HIV diagnosis, Black adults in communities with the highest social vulnerability might find it harder to obtain HIV prevention and care services because of various factors, such as poverty, limited access to health care, substance use disorder, transportation to services, housing insecurity, HIV stigma, racism, discrimination and high rates of sexually transmitted diseases.”

“HIV strategies, interventions and programs that address the needs and challenges of Black adults in communities with the highest social vulnerability are needed,” they added. “The development and prioritization of interventions that address social determinants of health (i.e., the conditions in which persons are born, grow, live, work, and age) are critical to addressing the higher risk for HIV infection among Black adults living in communities with high levels of social vulnerability. Such interventions might help prevent HIV transmission and reduce disparities among Black adults.”

Click here to read the full report.

Click here to learn about the Black researcher who called for equity in 1988 and to read more news about Black people and HIV.

Comments

Comments