Marlon RiggsWikipedia

When the Black gay documentary filmmaker Marlon Riggs died of AIDS complications at age 37 in early April 1994, the pioneering director had not completed his final film, Black Is…Black Ain’t. A probing look at Black identity, the film, which was completed posthumously by his collaborators, is, like his previous works, experimental and features prominent voices, such as bell hooks and Cornel West. Strikingly, it also includes footage of Riggs lying in his hospital bed during the final months of his life.

“Because of the likelihood that you could die at this moment,” Riggs says in the film, “AIDS forces you to deal with that and to look around you and say, ‘Hey, I’m wasting my time if I’m not devoting every moment to thinking about how can I communicate to Black people so that we start to look at each other, we start to see each other.’”

Yet even while in the hospital, he displays the cheeky, winking humor that infuses his other films. For example, at one point, he expounds on the history of Black American music in an exaggeratedly enunciated voice, almost as though channeling Maya Angelou at her most stentorian.

Black Is…Black Ain’t was the final chapter in a short but remarkable life. Born in Fort Worth, Texas, Riggs was the child of civilian military employees who moved often. As a child in Georgia, Riggs recounts in a searing section of Tongues Untied, his best-known work, he was called racial slurs by white students and gay slurs by both Black and white students. Later, in Germany, where his parents were stationed, he excelled in his American expat high schools before returning to the United States to attend Harvard, where he concentrated on the study of racism and homosexuality, graduating magna cum laude in 1978. He then earned his master’s degree in journalism from the University of California, Berkeley (specializing in documentary filmmaking), where he eventually became the university’s youngest tenured professor.

Riggs worked on other people’s documentaries, editing and working in postproduction, until in 1987 he made his first film, Ethnic Notions, an unflinching look at degrading characterizations of Black people in live performance, literature, animation, songs, advertisements and film in the 19th and early 20th centuries. (The film was narrated by actress Esther Rolle, who played matriarch Florida Evans on the 1970s sitcom Good Times.)

Two years later, Riggs released Tongues Untied, an exploration of how gay Blackmen are caught between often homophobic straight Black culture and often white supremacist gay culture, that featured documentary footage and poetry and in some ways borrowed from Ntozake Shange’s pioneering 1976 stage “choreopoem,” For Colored Girls….

Lauded by film festivals, Tongues Untied—with its frank depiction of Black gay male sexuality, including kissing—outraged cultural conservatives upon its release. Indeed, right-wing Republican Senator Jesse Helms cited it in his argument for discontinuing government funding for the arts. (Some $5,000 of the film’s budget had come from a subgrantee of the National Endowment for the Arts.) Republican Pat Buchanan even went so far as to use a clip of the film in a political ad against President George H.W. Bush (whom he was challenging for the presidential nomination) claiming that his administration was funding obscenity.

But today, at a time when mainstream depictions of Black gay men are more common, the film is regarded as a pathbreaker, beloved for its many memorable segments, including one in which a various gay Black men demonstrate different ways of snapping their fingers to punctuate their words. It also features lines of Riggs’s own poetry throughout, such as, “Anoint me with cocoa oil and cum so I speak in tongues, twisted so tight they untangle my mind.” In 2022, the film was added to the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry.

Riggs followed Tongues Untied with 1992’s Color Adjustment, a look at depictions of Black people on TV—from the early 1950s Amos ’n’ Andy, which the NAACP protested for its demeaning portrayals, to the aspirational 1980sThe Cosby Show. Once again, Riggs used nontraditional techniques to drive points home. To show how the goofy character of J.J. on Good Times harked back to the buffoonish minstrelsy of early 20th century Black characterizations, Riggs overlaid slow-mo footage of actor Jimmie Walker clowning around as J.J. with vintage images of minstrel performers.

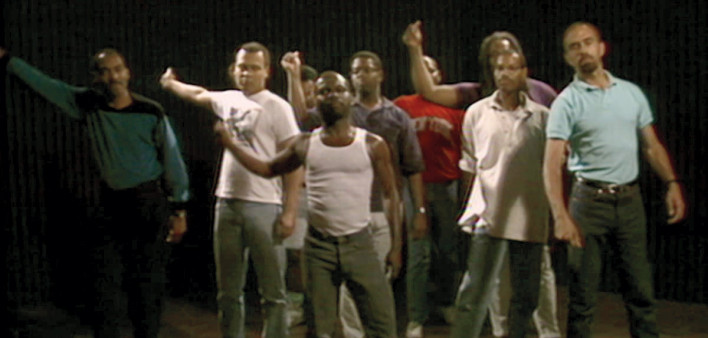

In 1993, Riggs released the short film Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien (No Regret), in which he appeared with other Black gay men living with HIV, including poet Assotto Saint, who died of AIDS complications a few months after Riggs died. The film featured music, poetry and frank discussions of the fear and stigma associated with HIV.

Riggs was survived by his parents and sister as well as Jack Vincent, his lover since 1979. Vincent is among those who have remembered that, as sick as Riggs was in his final year, whenever he felt halfway decent, all he talked about was finishing Black Is…Black Ain’t. As Riggs himself says in the film, “If I have work, then I’m not gonna die. ’Cause work is the living spirit in me, that which wants to connect with other people and pass on something to them they can use in their lives."

Comments

Comments