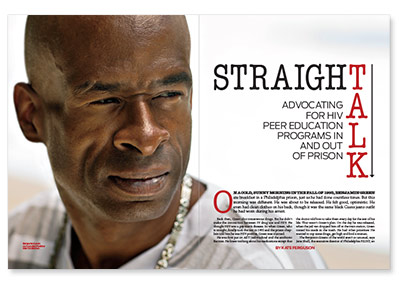

Back then, Green shot intravenous drugs. But he didn’t make the connection between IV drug use and HIV. He thought HIV was a gay man’s disease. So when Green, who is straight, finally took the test in 1993 and the prison chaplain told him he was HIV positive, Green was stunned.

He was first put on AZT (zidovudine) and the antibiotic Bactrim. He knew nothing about his medications except that the doctor told him to take them every day for the rest of his life. That wasn’t Green’s plan. On the day he was released, when the jail van dropped him off at the train station, Green tossed his meds in the trash. He had other priorities: He wanted to cop some drugs, get high and find a woman.

The Benjamin Greens of the world aren’t so unusual, says Jane Shull, the executive director of Philadelphia FIGHT, an HIV/AIDS service organization located in the heart of the city’s historic and business districts. FIGHT founded the Institute for Community Justice when it became clear that large numbers of people seeking the organization’s services were arriving there from jail.

“There seemed to be a revolving door,” says Shull. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 1 in 7 persons living with HIV pass through a correctional facility each year.

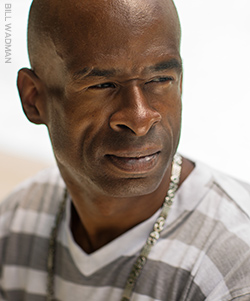

Larry Watson is one of these statistics. When Watson took the HIV test as part of a drug and alcohol treatment program in 1994, he thought he knew his status. “I’d just finished serving a five-year prison sentence and I had tested negative before I was released, so I just knew this result was going to be negative also,” says Watson. It wasn’t.

Since 2006, Watson has been an inmate at the Allenwood Federal Correctional Complex in White Deer, Pennsylvania. At Allenwood, he learned firsthand about the HIV stigma and ignorance that still persevere. During a basketball game, Watson, who’s never hidden his status since he’s been incarcerated, got scratched and one of the other inmates saw blood on his shirt.

“He said something to another guy, and they stopped the game,” Watson says. “The most major misconception is about how the virus is transmitted through blood. If they see blood, they get scared.”

Another time, Watson saw a phrase written on his housing card saying that he had “the bug.” And once while at work in the kitchen pouring ketchup in containers, the steward took exception to him doing this job. Watson says the steward told him, “Listen, don’t be pouring that in there. Don’t you have the issue?” (In prison, HIV is sometimes called “the issue” or “the package,” he says.)

|

| Larry Watson |

Such incidents inspired the Newark, New Jersey–born Watson to educate fellow inmates about the virus. Every Tuesday and Thursday afternoon Watson holds classes about how to prevent HIV transmission, how the virus is treated and how to become an activist, “for those who may want to become involved,” he says.

In addition, with help from some institution staff members, Watson even connects inmates to care if they ask him for help. “There were several men who didn’t take my class who told me they were infected and were soon to be released,” Watson says. “One of the treatment specialists here helped get approval for me to make some calls for these individuals and hook them up with appointments for when they got on the outside.”

In 2009, Watson called on his training as a graduate of Philadelphia FIGHT’s Project TEACH (Treatment Education Activists Combatting HIV), an HIV health education program offered by the organization, to launch a peer education program for heterosexual inmates at the institution.

“At Outley House, the emergency shelter, that’s where I saw firsthand the lack of work being done in the heterosexual community,” Watson says. “If you weren’t gay or a drug user, the information wasn’t getting to you, and some people didn’t care to try to find out information because they thought becoming infected couldn’t possibly happen to them since they didn’t fit into either one or the other of those two population groups.”

In general, HIV experts believe peer education programs can help prevent transmission of the virus. The CDC suggests “education programs delivered by peer educators are particularly effective in establishing the trust and rapport needed to discuss sensitive topics related to sexual practices, substance use and HIV.”

But for peer education to be as effective as possible, Watson suggests, these programs must have more heterosexual men on staff, people who look and talk like the population they’re trying to reach.

Adds Watson, “They hired me at GALAEI to be an outreach worker right after I graduated from Project TEACH. I was an HIV-positive, heterosexual male who was from the places they weren’t going to and a part of the population group they weren’t reaching.”

According to findings published in the Journal of Correctional Health Care from 2007, the most current data, only 18 states, or just 20 percent of U.S. prisons, have HIV peer education programs. “Despite the success of these programs, most facilities are not using them for educational or rehabilitative purposes,” notes Kimberly Collica-Cox, PhD, the study’s author.

For these programs to work, says the CDC, they should address risk inside and outside of the correctional setting. In addition, the programs should offer the tools to enable people to implement safer-sex practices inside prisons. That means “providing condoms and clean syringes,” the CDC suggests, before pointing out a main challenge: “Most U.S. prisons and jails specifically prohibit the distribution and possession of these items.”

Although peer education programs work, when activist Mujahid Farid, now 65, teamed with fellow inmates in 1987 at Auburn Correctional Facility in Auburn, New York, to launch an AIDS education group, they faced stiff opposition. Farid and fellow inmates presented a proposal to Auburn’s prison administration for a program called Prisoners Education Program on AIDS, or PEPA. In efforts to extinguish the HIV peer education spark, prison officials separated Farid and his collaborators, but that only fanned the flames.

A group of female prisoners picked up from there, launching ACE (AIDS Counseling and Education) at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, in Bedford, New York.

In the latter part of 1988, Farid, who had been transferred out of Auburn to Eastern New York Correctional Facility in Napanoch, and his colleagues finally launched their AIDS education group. PEPA was now renamed Prisoners for AIDS Counseling and Education, or PACE.

“The program pretty much spread all over the state from there,” Farid says.

|

| LaDonna Boyens |

A little more than 14 years ago, Boyens first learned that she was HIV positive. She remembers the exact time: September 18, 2000, at 11:45 a.m. Boyens, who is also a spinal cord injury survivor, says she’d been engaging in “some self-destructive behaviors.”

Says Boyens, “I was mad at the world, and I was taking it out on everybody else.” She acted up, and her anger landed her in jail for a few days. She didn’t know it at the time, but that short stay would prove useful.

“At one time, I didn’t have anybody to talk to,” she says. That moment of loneliness motivates her current advocacy. “That’s the part I want to play. I want to be there for these women, so they can get some things off their chest and don’t have to carry it around and engage in negative behaviors after they leave jail. I don’t have all the answers, but I ask other people, or we look things up together. I try to be there for them with as much information as I can.”

“Jail is jail,” says Boyens, a co-chair of the Philadelphia chapter of the Positive Women’s Network. “Men and women in jail face overcrowding, not getting their meds on time, not wanting anybody to know about their diagnosis, and not taking medication because they don’t want people to know their business. That’s sad.”

When incarcerated men and women are diagnosed with HIV, these correctional settings are where many learn for the first time they have the virus. But, notes the CDC, “although HIV testing is practical and acceptable in jails and prisons, inmates are hesitant to be tested for a number of reasons.”

Green—the man who ditched his HIV meds the day he was released—experienced two of these reasons when he eventually “started shooting drugs and getting high again” and found himself back in prison. While there, he received a pass to go to medical call. But Green noticed something different written on it. The guard noticed it too, Green says, and looked at him “in a strange way.”

Now thoroughly uncomfortable, convinced the guard knew his HIV-positive status, Green worried his secret might get out. Then he applied for a job in the kitchen at the institution. Green says he was told he wasn’t eligible for the position because he hadn’t been sentenced yet. “But I knew dudes who weren’t sentenced who were working in the kitchen,” he says.

Unlike Green, Watson constantly disclosed. “I talk about HIV whenever. I never want my status to be a secret again because that kept me depressed for a long time,” he says. “I was in a four-year relationship with a woman who was HIV negative; that did a lot for me because once I told her, she accepted it.”

Adds Watson, “I felt like, OK, I educated her, I’ll educate other people in my life who have issues with it, and if they don’t accept it, then it is what it is.”

Statistics show that HIV prevalence is high in U.S. prisons. But “the data may underestimate both HIV prevalence and incidence due to existing stigma and fear,” says a report by the HIV/AIDS group GMHC (Gay Men’s Health Crisis). “This stigma not only leads to nondisclosure of HIV-positive status, but also places prisoners at an elevated risk of infection.” Without testing and education efforts, the inmates may take HIV back to their communities.

But inmates aren’t the only ones concerned with stigma and fear. Prison staff require outreach as well. To normalize the presence of HIV in county jails, each June, during AIDS Education Month, Philadelphia FIGHT’s staff covers all three shift changes at nine local facilities. Staffers speak for a few minutes to corrections officers about HIV, so they’ll be less anxious about their risk of acquiring the virus on the job.

“We want to help them understand that they play a really crucial role,” says FIGHT’s Jane Shull. “And to the extent that they help battle stigma, they’re fighting for everybody in prisons or jails, and it makes a big difference.”

FIGHT also partners with federal detention centers to conduct workshops and resource fairs. In general, county and federal facilities operate differently, and FIGHT works most often with county jails. But “all of these entities to some degree or other have participated in our annual Prison Health Care Re-entry Summit,” Shull says. “I would say that we have absolutely played a role in coordinating services.”

But Watson believes FIGHT and other HIV/AIDS service organizations around the country “only go to county prisons where there is a revolving door, which means the same people are receiving services over and over.” What’s missing is outreach to the federal and state penitentiaries.

“They go to the county prisons in their city and do case management or outreach,” he says. “No one comes to the U.S. penitentiaries because—I’m not going to lie—it’s hard to get approved to get in here. But if they were to try, I can guarantee that these people will work with them. The prison I’m in is one of the highest-security penitentiaries there is, and they’ve been great about trying to help people.”

Shull readily admits that FIGHT works within the limitations of the system. “Our view is that we get a lot farther working with the system,” she says. “We certainly advocate, but we try not to do it in an adversarial way. We try to push the envelope one or two steps up.”

In their own way, too, Green, Watson and Boyens must all work within limitations inherent in the justice system they’ve come to know so well. But their passion for peer education keeps them pushing forward as well.

|

| Benjamin Green |

Green regrets bypassing Philly FIGHT’s open doors years ago. “I let that opportunity pass because of my own prejudices and fear,” he says. “Maybe I could have learned more about HIV and myself just by going there. But I stayed on the street another 12 years. Luckily, God was with me and I didn’t die.”

Back when he was first released, Green couldn’t wait to get high and find a woman. Well, a little more than two years ago Green got hitched. He says his wife is his peer and his strongest supporter at home.

This, he says, is one of the most important and powerful messages he can give to straight men struggling with HIV stigma—that he, as a man living openly with the virus, “got married to a wonderful woman named Maria.”

3 Comments

3 Comments