AIDS activists in Los Angeles expressed “shock and deep sorrow” at the death of Mary Lucey and Nancy Jean MacNeil, two lesbian warriors who joined ACT UP Los Angeles in 1990 and elevated the issues of women, prisoners and HIV. The two were together for over 30 years and eventually married. Both died Saturday, February 11, 2023. A cause of death was not listed in a statement from ACT UP Los Angeles Oral History Project.

Mary Lucey and Nancy Jean MacNeilPhoto by Peter Cashman

Lucey and MacNeil, along with fellow AIDS activists Jordan Peimer, Helene Schpak and Judy Ornelas Sisneros launched the history project on World AIDS Day 2021 with the goal of documenting HIV activism in the Los Angeles area from 1987 to 1997, notably the work of the local chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). For more about that, read the POZ article “Memory = History = Knowledge = Power” and visit actupla.org.

When Lucey joined ACT UP, she was living with HIV and had been incarcerated, which gave her firsthand experience of the neglect and discrimination that HIV-positive women faced in prison. It fueled her activism and led her to become a rare public face of women living with HIV. MacNeil was also a longtime activist, having fought for feminist, Black and antiwar issues.

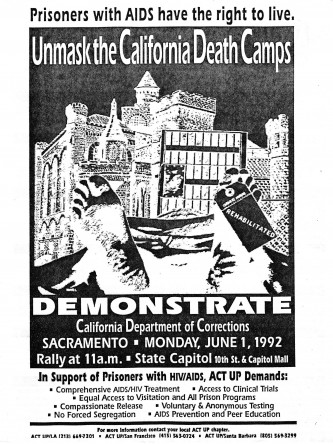

Graphic from a 1992 ACT UP flyer bringing attention to prisoners with AIDS, an issue important to Mary Lucey and Nancy Jean MacNeilCourtesy of Judy Ornelas Sisneros

Fellow HIV advocates mourned their loss. “I was and am shocked at the loss of both Mary and Nancy,” said Terri Ford, the chief of global advocacy and policy for AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF), in a statement. “True warriors, fighters and fun seekers. I advocated alongside them for many years in ACT UP and I learned a lot from them. They were passionate about prison issues and the inclusion of women in the HIV/AIDS battle for treatment and to stay alive. Nancy also worked for AHF for a time with me in the kitchen at Chris Brownlie Hospice. That was great. Mary visited often. We are talking early 1990s—I call them the holocaust years. So many were dying tragic deaths. But Mary was an outspoken HIV-positive fighter and took no prisoners. She was fighting for her own life and those of others without a voice. Their legacy will live on. I wish both Mary and Nancy safe refuge wherever they are. They are together and that is what matters.”

“I met Mary Lucey in the early ’90s when she was advocating for women living with HIV/AIDS. We were members of the LA County HIV/AIDS Women’s Caucus. We became friends and the rest is history,” said Cynthia Davis, MPH, assistant professor at the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science and vice chair of AHF’s board of directors.

“Mary was going from clinic to clinic in LA County trying to identify one clinic which would start a specialty clinic for women living with HIV/AIDS,” Davis recalled in the AHF statement. “Every clinic was turning her down for multiple reasons including, ‘if we start serving HIV-positive women the clinic would become “stigmatized” and their clients would go elsewhere.’ I went to Mary and told her about T.H.E. Clinic for Women in South Los Angeles, then directed by Sylvia Drew Ivie. I arranged a tour of T.H.E. Clinic and Mary fell in love with it. An agreement was made and one of the first dedicated HIV/AIDS Clinics for women in LA County opened in the early 90s at T.H.E. Clinic for Women. I also worked with Mary when she was the AIDS Coordinator for the City of L.A. Mary’s strength, love and unselfish dedication to women living with HIV/AIDS will never be forgotten.”

POZ will update this article as more details become available, but the deaths are thought to be due to natural causes. To learn more about the women’s contributions to HIV, LGBTQ and women’s issues, visit their bios on actupla.org, which were posted for the launch of the ACT UP Los Angeles Oral History Project in December 2021. Below are selections taken from the website bios:

Video capture image of Mary Lucey circa 1992 from an ACT UP Los Angeles videoCourtesy of Judy Ornelas Sisneros

Mary Lucey

In 1989 Mary Lucey was fighting drug addiction while simultaneously pregnant and diagnosed HIV positive. She had also recently completed an 18-month sentence at California Institute for Women, Frontera.

After nearly 10 years into the epidemic there was only one medication that was available to Lucey, the highly toxic AZT which she had to take around the clock. She boldly faced the discrimination, stigma and fear associated with an HIV/AIDS diagnosis, which at the time was still considered a death sentence.

In 1990 Lucey got a handle on her addiction, met her future wife Nancy MacNeil, and found her voice in ACT UP Los Angeles. She joined the group after they attended the first Women’s Caucus meeting in June of 1990.

Lucey, a loud and proud lesbian was among the first HIV-positive women in Los Angeles to be out about her status. Fueled by a sense of outrage at AIDSphobia, she fought for several years in ACT UP to expand the CDC’s definition of AIDS to include women’s opportunistic infections and for health care for incarcerated women with AIDS. In 1992 Lucey’s advocacy work for compassionate release for women in prison with AIDS led to the first U.S. release of such a prisoner, Judy Cagle, enabling her to die at home with dignity.

Lucey became more powerful, fearlessly outspoken and willing to confront government officials at every level. She was often asked by ACT UP to provide testimony to government agencies and legislators…and was often interviewed for numerous newspapers and magazines.

In 1994 Lucey worked as the first woman City AIDS Coordinator on an interim basis where she, along with other staff, funded the first needle exchange program from the City of Los Angeles. This program, an offshoot of ACT UP LA originally called Clean Needles Now, is currently known as the LA Community Heath Project. It was calculated to prevent 12,000 new HIV infections each year.

Lucey also founded the first peer support group for positive women in 1990 and co-founded Women Alive, a support and advocacy group. She raised money for and organized the 1997 National Conference on Women and AIDS held at the Convention Hall of the Los Angeles Staples Center. It was the largest gathering of positive women in the country at that time.

Since then, Lucey has continued to stay involved as a community activist. She won a position on her local community services board representing the town of Oceano. She served for two consecutive terms.

Lori Avila and Nancy Jean MacNeil at the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association action during the 1993 March on WashingtonCourtesy of Judy Ornelas Sisneros/Mary Lucey

Nancy Jean MacNeil

Nancy Jean MacNeil was born in Los Angeles and grew up running the Avenues of Highland Park. In the Vietnam War era, Nancy organized sit-ins and walkouts with fellow students at risk for the draft in high school. She continued to attend peace rallies, marches and pickets. She joined the Black Panther Party to fight against police brutality and helped with their breakfast programs in downtown LA. (The BPP encompassed Black people and poor Whites.)

MacNeil was labeled an “outside agitator” on California college campuses, enduring multiple encounters with vicious men cloaked in police uniforms while protesting against war and police brutality. Engaged on various levels with People’s Park in Berkeley and the Isle Vista Uprising in Santa Barbara, she witnessed the infamous burning of the Bank of America in protest of the use of napalm in North Vietnam.

She attended the Institute for The Study of Nonviolence in Palo Alto and visited federal prisons housing the boys who said “NO” to the draft.…

In the ’70’s and ’80s she became active in the gay and lesbian community, joined several women’s rights groups as well as the Lavender Left…. In May of 1979 she participated in the “White Night” riots in San Francisco when the verdict of voluntary manslaughter was announced acquitting Dan White of first-degree murder for the killing of Supervisor Harvey Milk. MacNeil was again brutalized by police and sustained multiple injuries from whirling billy clubs.

From the onset of AIDS, while it was still being referred to as gay cancer or GRID, MacNeil was losing friends to the disease. Her first friend to die of AIDS was Julian Turk in 1982. He’d been diagnosed by Dr. Michael Gottlieb at UCLA who was the first to report the disease that would come to be known as HIV and AIDS. She was exhaustively surrounded and saddened by the weekly loss of so many close and dear friends. This compelled her to try and turn the tables. She joined ACT UP in 1990 after attending the first Women’s Caucus meeting.

She also joined the Prisoners with AIDS subcommittee and the ACT UP National Network. MacNeil attended the AIDS Clinical Trials Group in Washington, DC, to confront researchers about scientific and ethical questions surrounding women in the government-funded treatment studies. Dosages and effects of AIDS medications on women’s bodies were still unknown and inclusion of women in clinical trials was urgently needed.

MacNeil joined fellow activists as they perpetually disseminated information, analyzed clinical data, wrote letters and postcards, zapped the opposition with faxes and phone calls and helped to organize demonstrations. She also helped to organize enormous die-ins to illustrate mass deaths to shock and shame the government and media into publicizing the AIDS crisis that was being ignored.

MacNeil became the founding executive director of Women Alive, an organization by and for HIV-positive women with a membership of over 500. She established a treatment-focused newsletter (quarterly distribution of 10,000) and the first National women’s AIDS hotline and empowered women with AIDS to become their own advocates.

She identifies as a situational pacifist dedicated to fighting for social justice and sincerely believes that women and queers will save the world. It is written in her heart.

1 Comment

1 Comment