Prior to his departure as head of the national institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Anthony Fauci, MD, spoke with Mitchell Warren, executive director of AVAC, on November 28, 2022, in advance of World AIDS Day. In the interview, they discuss what has been accomplished so far in the fight against HIV and COVID-19 and what’s ahead for Fauci and pandemic preparedness. Below is an edited excerpt.

Mitchell Warren: What do we need to do differently in the next three to five years to meet the ambitious HIV goals set by the global community for 2030?

Anthony Fauci: We need to get back on track at the pace that we were on before we got hit with COVID—from the availability and ease of testing to the treatment supply chain, from outreach to the community to even the research endeavor itself.

Many people who otherwise would have been involved in HIV research essentially switched emphasis temporarily out of necessity. Many clinical trials came to a standstill because of the restriction of getting people into the clinic or into the hospital to study. We have to reset and reenergize.

Despite the stress of the last three years on the system, much has been accomplished. Particularly as an example is the proof of the extraordinary efficacy of long-acting injectable drugs for both HIV prevention and treatment. These could be game changers for us.

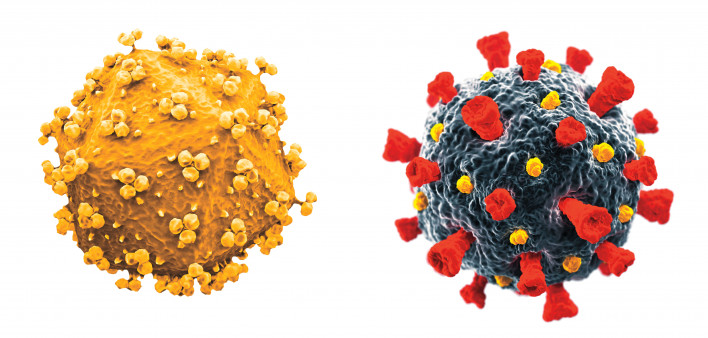

For the immediate future, it will be very exciting to apply to HIV the advances in vaccine technology that were hugely successful with COVID. We now have a number of trials that are going on from preclinical to Phase I using an mRNA platform for an HIV vaccine.

We also are seeing applications of some of the immunogen design that was so successful with COVID, where we utilize the stabilization of the prefusion configuration of the viral spike protein, which turned out to be extraordinarily effective.

These are all lessons that we learned from COVID in the same way that HIV informs some of the successes that we got with COVID.

Anthony Fauci, MDNational Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Mitchell WarrenCourtesy of Mitchell Warren

To what degree as researchers and as funders of research do we need to turn from biomedical product development to the often harder work of delivery?

As far as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), if you look at the numbers, it is not being maximally utilized, particularly among some of our minority populations, which is really unfortunate.

We’ve got to get user-friendly PrEP to them. That’s going to involve implementation that integrates itself into the health care delivery system. Otherwise, we’re going to have highly effective interventions that are not being used, and that would really be a big mistake.

A very critical point in the success or not of ending the HIV epidemic is continuing with new discoveries. There are always new things that we need to discover. And we’ve done a very good job of that. But it’s important that we implement them, and that’s something that we are going to be making significant investments in.

We’ve got to keep everybody’s feet to the fire, including the appropriators, who might think, We’re doing so well, we don’t need new resources. We need increases in HIV commensurate to at least and maybe more in some respects than for other areas.

Remember, we went through a very disturbing period where everything was flat for a very long period of time with the misperception that you don’t want to get above a certain percentage of the budget, which is nonsense. It should be determined by the scientific opportunity and the public health need. Hopefully, that’s what we’ll be doing.

You’ve been such an effective spokesperson to policymakers and the public, what are we going to do without you?

There are a lot of good people that can do this. I want to emphasize that I am not stepping away from my passion for ending the epidemic and getting attention to the importance of resources. I’ll be doing it in a different venue, but that venue could perhaps be equally if not more effective. I’m not disappearing.

I am not stepping away from my passion for ending the epidemic and getting attention to the importance of resources.

Is it still possible in our lifetimes to see an HIV vaccine? And can we end the HIV epidemic without one?

Is it still possible? Of course. Is it difficult? Extremely.

It violates that rule of vaccinology that the best way to get a successful vaccine is to mimic a natural infection. When you get naturally infected with measles or polio, for example, when you recover, you develop a degree of immunity that protects you against reinfection from the same pathogen.

The correlate of immunity is unfortunately, and I might say tragically, not the case with HIV. Natural infection does not provide an adequate degree of immunity, which is why people can get reinfected and superinfected and virtually no one ever spontaneously gets cured of HIV by their immune system.

We’ve got to do better than natural infection immunity, and I think we can. We have the will and the wherewithal and the scientific commitment.

As for ending the epidemic without a vaccine, I also believe we can. If we implement long-acting injectables for PrEP and for treatment, I believe we can do it. We should not give up on the possibility of ending the outbreak by saying until we get a vaccine that we’re not going to achieve it.

It gets back to the principles of undetectable equals untransmittable. We need consistent widespread testing. If you are HIV negative, go on PrEP. If you are HIV positive, go on therapy. If we were able to do that 100% effectively, you would see the end of the epidemic without a vaccine. In that regard, a vaccine would be a bonus.

Coming out of COVID, where there was so much misinformation, what do we do to get out of this?

This may be one of the most important topics looking forward, not only for HIV but for all elements of science and public health. The divisiveness in this country, which feeds into the misinformation and disinformation, is truly profound. I have never in all of my career of 54 years here at NIH and 38 years as the director of NIAID ever seen this level of misinformation and disinformation.

I’ve always said that the best way to counter misinformation and disinformation is to flood the system with correct information. But it’s a very interesting situation that I’ve observed.

Usually, people have a lot of responsibilities, or, as they say colloquially, have day jobs. However, the people who are out there spreading ridiculous nonsense seem to have all the time in the world to spread misinformation.

It’s almost like we’re outnumbered when it comes to people who are spreading misinformation.

The only thing that I would say is that we can’t give up. People throw up their hands and say there’s so much anti- science filled with myths. We can’t give up, because if we do, there’s no counter.

In your career, what are some of the biggest successes and regrets?

At NIAID, it was developing the AIDS program that has been responsible, with industry, for the development of most of the drugs that have now saved millions of lives. As a policy person, it clearly was helping to develop the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

PEPFAR is a great example of what can be done when you have leadership and commitment from the highest levels of the country.

My biggest disappointment is that I wanted to be in this position when we developed a safe and effective HIV vaccine. It is just not turning out that way. But we’re not giving up.

Thank you for all that you’ve done. I’m going to let you have the last word.

It’s been such a great privilege, a pleasure and an honor to be leading this organization and to be getting involved, particularly with the relationships that we’ve developed along the way, with so many people and organizations.

I look forward to continuing to interact with you in a different capacity, which is soon to be determined but not quite yet known.

AVAC advances global advocacy for HIV prevention. Go to AVAC.org to learn more

Comments

Comments