Nearly 46 percent of America’s new HIV cases occur in the South. Men who have sex with men (MSM) account for 50 percent of new infections in the United States. Similarly, African Americans, which make up 13 percent of the population, comprise half of the country’s new HIV/AIDS cases.

|

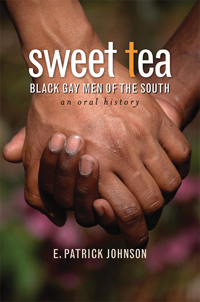

Given these overlapping statistics, it’s clear that gay black men in the South are at significant risk. But who are these men, and what are their stories? E. Patrick Johnson, PhD, offers an introduction to the real people behind the impersonal statistics. His book, Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South (University of North Carolina Press, $35) is a collection of first-person narratives of 63 African-American gay men.

It’s not a coincidence he chose that title—“tea” is slang for gossip in Southern vernacular. In reading each colorful story, it seems as if the men are indeed gossiping directly with you; many are gifted storytellers who offer fascinating insight and analysis on complicated topics. The subject of HIV weaves throughout the tales in different contexts: coming out, mourning the death of lovers, desiring skin-on-skin sex and faulting the black church for not providing outreach and education about AIDS. And since Southern gentility typically silences the HIV epidemic—proper folk don’t discuss such untoward matters—these stories are all the more powerful.

POZ spoke with Johnson about his book and its related one-man show to find out what he observed about the epidemic through his interviews.

You asked the interviewees whether HIV was a problem specific to the South. Was there an overarching response?

|

| E. Patrick Johnson, PhD |

There wasn’t an overarching response to anything! It really varied from person to person. But the prevalent responses were yes it is, and there was a belief that it was because people were more ignorant about HIV/AIDS in the South and also because of the general culture of “don’t ask, don’t tell”—that we don’t talk about anything [controversial or “improper”] and that leads to denial about it.

How did you find the level of education about HIV and how it spreads?

For the most part, everybody was fairly educated about HIV. Everyone knew the ways in which you contract HIV but had already worked out in their own minds the level of risk they would take. For instance, “I’ll use a condom if having anal sex but not oral sex,” but still knowing there is risk with oral sex.

You spoke with people ranging in ages from 19 to 93. That’s quite a spectrum. You mentioned that some of the older men seemed to associate AIDS with gay white men, but the younger ones didn’t. What other generational differences did you notice regarding the attitudes about HIV/AIDS?

A lot of folks who came of age pre- early ’80s lamented the fact that they can’t have sex without condoms anymore. They really missed that physical contact, and some of them talk about slip-ups and so on and so forth and how it was a different world when they were coming of age. But now they don’t have those experiences anymore unless they’re in committed relationships.

On the other side of that, a number of young people I talked with lament the same thing—except that they’ve never experienced condom-less sex.

Some of the older men expressed concern that younger guys weren’t using condoms.

And they believe that because there was a study done, I think in 2006 or 2004, about the rise of seroconversions among young black men at HBCUs [historic black colleges and universities] in the South. I think that that statistic along with some of the media coverage of this issue gives the impression that a lot of these young men aren’t using protection.

Was that your observation from your interviews with young people?

It wasn’t, actually. And again, my sample is skewed. But the young men I interviewed in college, again, were lamenting the fact they didn’t know what it was like to have sex without a condom. So that wasn’t their experience. That’s not to say that other folks weren’t having unprotected sex.

Did your interviews give you any insight into underlying trends or beliefs or situations—anything—that might be fueling the rate of HIV among blacks in the South?

That is long and complicated [answer, but] I’ll give you a redacted version. One of them is related to this whole down low phenomenon, and that is that [some folks] associate condom use with gayness. And so to use a condom means that you are naming yourself as gay. [One interview subject] brings it up in the context of women not taking responsibility for their own sexual health, in terms of not requiring men to use condoms and putting a stigma on men who did want to use condoms by disparaging them and calling them punks.

Another thing is pleasure. And one of the people I interviewed talks about this. He himself is HIV positive, and he tells the story about being in Piedmont Park in Atlanta, during, I think, Black Gay Pride, and watching all these people have sex. And as he was going around being a voyeur, he was giving people condoms. And then he tells this story about this one guy who was having sex with this hooker, and he chastise the guy later about having sex with this woman without a condom. He says some of [the reasoning behind unsafe sex] is ignorance and some of it is just wanting that skin-to-skin contact. So it’s about sexual pleasure.

And then the other reason is that it is in the heat of the moment. In the same way that teen pregnancies happen.

The black church is a dominant theme in the book. One of your interview subjects likens it to a dysfunctional relationship in which gay people are verbally abused from the pulpit but keep coming back because they like performing in the choir or socializing. Another subject feels that the church is happy to exploit gay people’s talents but then offers no HIV outreach. How has the church influenced the HIV epidemic in the south?

While a number of African-American churches are still in denial, there are some that have realized that this is something they can’t ignore anymore. Some churches have testing—the church is the testing site—and there are churches that provide outreach, sometimes not about education as much as it is about care so that it fits in with the general community of caring for the convalescent. That’s one way the church can make it “okay.” It’s not about sexual orientation; it’s about the illness. We separate it—it goes back to hate the sin, love the sinner.

Finally, how are people responding to your book and one-man show?

Black gay men are thankful that their stories have been affirmed. And I’ll share one anecdote—and I get this in the form of e-mails out of the blue and also letters people write to me. When I performed at the University of North Carolina at Chappell Hill, which is my alma mater, this grandmother e-mailed me and said, “I’m not black. I’m not gay. I’m a white woman who’s 75, and I’m a grandmother. I just want to say how brave you are for doing this work and how moved I am by these stories. Thank you for opening up your life and the lives of the men you’ve chronicled in your performance and in this book.” So those kinds of e-mails and stories make me realize how important this work is.

Johnson performs monologues based on his Sweet Tea interviews throughout the year across the country.

1 Comment

1 Comment