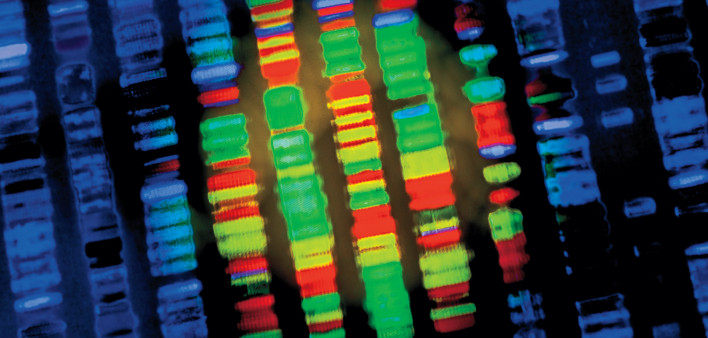

A new form of cancer screening known as multi-cancer early detection tests (MCED) uses gene sequencing to detect fragments of DNA produced by cancerous cells and circulate in people’s blood, allowing the identification of multiple types of cancer from a single blood draw.

The tests have been hailed as “revolutionary” and “cutting edge” by British and US health officials, and both countries have set up MCED clinical trials in hope that the tests can be rolled out to the public at large. The UK’s National Health Service is currently participating in a clinical trial of Menlo Park-based Grail’s blood test (dubbed "Galleri“) involving 140,000 patients. If the trial is successful, NHS officials say they’re ready to make an initial purchase of one million tests. A 35,000 patient study, dubbed ”Reflection," is currently enrolling in the US.

Galleri is pitching its test as a key tool that can help the Biden administration make progress on its "cancer moonshot" to reduce cancer deaths by half by 2041. And following intense industry lobbying earlier this year, US lawmakers introduced bipartisan legislation aimed at fast-tracking Medicare reimbursement for such tests. (The Senate version is S. 1873.) Because the test is not yet FDA approved, it is not currently reimbursed by even private health insurance and appears to cost around $1,500.

Following intense industry lobbying earlier this year, lawmakers introduced bipartisan legislation aimed at fast-tracking Medicare reimbursement for MCED testing.

The scientific breakthrough that led to the development of Galleri occurred a decade ago when Meredith Halks-Miller, a former laboratory director at gene-sequencing company Illumina, spotted abnormal DNA fragments in the blood of expectant mothers. She had a hunch that cancer was the only thing that could cause the particular pattern of fractured chromosomes and began following the otherwise healthy patients.

“All the mothers whom we predicted to have a malignancy were diagnosed with cancer shortly after delivering their babies. It was a revelation,” says Halks-Miller, who has since retired.

Halks-Miller’s discovery fired the starting gun on the race to develop a diagnostic blood test. Illumina spun off a new company, Grail, to develop the test, raising more than $2 billion from investors including Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and the Chinese company Tencent.

Galleri tests work by using genetic sequencing and artificial intelligence to scan a certain type of DNA — cell-free DNA — found in people’s blood for changes caused by cancer cells. This analysis can provide a signal that cancer is present and give information about where in the body the signal originated from.

Grail published the results of a study of almost 6,700 participants aged 50 years or over last September. Of 92 participants flagged with a potential cancer signal, about 35 participants were diagnosed with cancer. All but 10 of these diagnoses were for cancers that did not have routine cancer screening programmes in place. Fifty-seven were false positives, almost a third of which prompted an invasive procedure to rule out a cancer diagnosis.

Of ninety-two participants flagged with a potential cancer signal, fifty-seven turned out to be false positives.

Other competitors such as Exact Sciences, based in Wisconsin, and San Francisco’s Frenome, a start-up backed by Roche, are racing to launch their own tests.

Claims of the “revolutionary” technology, though, have understandably been met with skepticism following the Theranos scandal, whose demonically telegenic spokesperson cofounder, Elizabeth Holmes, apparenty lost one last last-ditch attempt (just now) to remain at home while continuing to appeal her 11-year sentence and is due to report to the Bryan, TX pokey next Tuesday. She and Balwani ex were also ordered (just now) to pay $452 million to victims of their fraud.

And critics of MCEDs point both to such a test’s overall effect on cancer mortality as well as its uneven record of accuracy: in a Galleri pilot screening program of Arizona firefighters (a high-risk group due to their regular exposure to environmental toxins), the test missed fifty cancers later diagnosed via full-body MRI.

Research also shows that there are drawbacks to screening for certain types of cancer, especially for cancers where there is limited evidence that early detection and treatment saves lives. Such super sensitive technology might pick up the tiniest of signals from a tumor so small it would be unlikely to cause any health issues during a person’s life. The MCED test can even pick up a cancer signal when the body is cancer-free.

In a pilot screening program of three thousand firefighters, Grail’s Galleri missed fifty cancers. And accurately detected three.

On the flip side, as in the Arizona firefighters experience with Galleri, screening can fail to detect cancers, providing a false sense of security and encouraging patients to disregard any symptomology. As breast cancer mammographers know all too well, up to 30% of tumors are missed by such screening.

In nearby Mesa, AZ, a publicly funded screening program gave one firefighter the “all clear” from Galleri only to find a brain tumor on full-body MRI. Biopsy-confirmed later, he is now completing treatment.

One of the physicians involved in the screening program says her experience testing the firefighters provoked mixed emotions. “As an oncologist, I love the concept. Cancer is a pandemic and we need a safe way to screen younger patients and blood tests are very safe. There is no radiation and it’s minimally invasive,” she says. “But it missed almost fifty cancers. This provides a false sense of security to patients, who may not want to do additional screening that could pick up their cancers.” She finds it “upsetting” that Grail continues to promote its test to firefighters even when she presented the company with her evidence. Additional testing is needed in younger, high-risk populations if the test is going to be marketed to them, she adds.

One of my MD author heroes, H. Gilbert Welch of Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital and author of "Overdiagnosed," among other books, notes that while this new MCED technology (or later upgrades to it) will almost certainly prove useful for something some day, it would be a mistake to roll it out without first performing the long-term studies that prove it can actually save lives.

To this point, a leading cancer geneticist-epidemiologist at Cedars-Sinai Department of Computational Biomedicine notes that, “first and foremost you need to measure whether the test applied in a screening program reduces mortality.” And a colleague at King’s College London cautions that “the more of this kind of screening you do on healthy people, the more errors you’re going to get.”

“My guess is that this is a quagmire that will cost governments and individuals tons of money” without providing any commensurate benefit, either in healthcare cost savings or years of life. “If we were to test all Americans over age 50 with this technology,” he adds, “we’re talking $100 billion a year.”

Recall that the Arizona firefighters pilot screening accurately detected three cancers from 3,000 screenings, produced two false positives, and fifty false negatives.

“Screening is like a modern form of bloodletting,” the King’s College professor added. “If you died, it’s because we didn’t leech you early enough; and if you didn’t die, it’s because the leeches saved you.”

Mike Barr, a longtime Poz Contributing Editor and founding member of and scribe for the Treatment Action Group (TAG), is a functional medicine practitioner and herbalist in NYC. Reach out to him here. Feel free too to sign up for his carefully curated (and generously discounted) online supplement store.

Comments

Comments