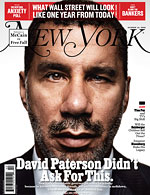

The situation reminded me of the frustration that I felt when I read recently that New York Governor David Paterson vetoed an essential piece of legislation critical to the HIV community and to those at greater risk for infection. Had bill A.9915/S.7306 passed, it would have allowed sexual assault survivors to be given PEP free of charge post assault if they could not afford the treatment themselves through private health insurance.

The idea of the bill was to provide $80,000 of financial assistance from the state budget to the Crime Victim’s Board to help those who could not pay for potentially life-saving PEP. The bill was introduced earlier this year by Assemblywoman Ellen Jaffee (D-Rockland) and Senator Thomas Morahan (R-Rockland) and passed both houses. That’s $80,000 total for one year to cover the cost of all those estimated to need this type of post trauma care versus the hundreds of thousands of dollars it costs, per person, to treat a sexual assault survivor who contracts HIV and has no health insurance.

Regardless of the economics, which seem to make perfect sense, it seems criminal to me that a woman who is unable to afford medication that can save her life should be denied access to it. Especially when she has just suffered huge mental and physical trauma, in some cases, probably just barely escaping with her life.

I wrote about this same issue last summer in an Op-Ed piece that ran in Newsday (read it here.) When I wrote that piece, Eliott Spitzer was the governor of New York. It was before we had heard about his extramarital transgressions. At the time, his suggestion was that rape survivors only get access to PEP if the state located, caught and correctly identified a rape suspect, convinced the suspect to agree to HIV testing and collect a positive HIV test result - all within 72 hours of the attack. The chances that all those things would happen, within 72 hours, seemed slim. If they were not accomplished, then a woman who, through no fault of her own, had potentially been exposed to HIV would be denied access to medical care that could save her life. The rationale for denying PEP to women who had been raped was the same then as it is now - supposedly, saving the state money.

Can you imagine the uproar if the same thinking shared by the current and ex-governor was applied to how we handle the post-exposure treatment of health care workers? Let’s see, why don’t we recognize that there are cases when surgeons, doctors, nurses, paramedics and nursing assistants are potentially exposed to HIV. And, rather than providing them with immediate free access to medication to save them, let’s tell them that first, we’re going to have to locate the person they operated on or cared for in a hospital bed or ambulance, convince that person to agree to be tested for HIV, wait for the result and then offer the health care worker PEP all within 72 hours of potential exposure, or else...or else they would just possibly have to become infected with HIV. And what if they couldn’t afford if - even after all of that? Well, we’ll just have to let nature take its course.

In a nation where we have recently revised the number of new HIV infections we see each year (up by 40 percent from the previously reported 40,000 to the new 56,300) and where an increasing number of those cases are among women, why we would not vehemently protest ANY local, state or federal policy that prevented people from accessing medication that would save people from becoming HIV-positive, thereby stemming the future spread of HIV is a question I can’t seem to answer. Anybody have any ideas? Help me understand this one...

1 Comment

1 Comment