It looks like new HIV diagnoses in Eastern Europe and Central Asia continue to rise. As Medscape Medical News reports, preliminary data for 2017 bolster the warning about the epidemic in the region issued by public health officials last year.

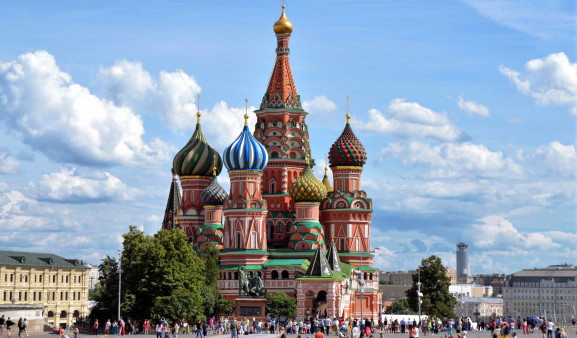

In 2016, there were 160,453 new HIV diagnoses in the region, according to the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) in Stockholm. Most were in Russia, which saw 103,438 new cases. (Other countries in the region include the Baltic states, Belarus, Georgia, Romania, Russia, Tajikistan and Ukraine.)

When official numbers for 2017 are reported in November, Russia will tally about 104,000 cases. Nearly half of the cases in the country are a result of shared needles among injection drug users.

“I keep thinking, this is sub-Saharan Africa happening all over again,” Linda-Gail Bekker, PhD, the president of the International AIDS Society, told Medscape.

In Eastern Europe, nearly 25 percent of people living with HIV don’t know their status; of those who do know they have the virus, only 46 percent are taking antiretrovirals. It’s important for people with HIV to know their status and adhere to their meds not only so they can live healthier and longer lives but also so they don’t transmit the virus to others; people who maintain undetectable viral loads cannot transmit HIV through sex.

The situation in Eastern Europe comes into clearer light when compared with its western neighbor. In Western Europe, 6.2 of every 100,000 people were diagnosed with HIV in 2016. In Eastern Europe, it was 50.2 of every 100,000.

Anastasia Pharris, PhD, of the ECDC, tells Medscape that countries could take steps to curb these HIV rates. For starters, more countries could implement test-and-treat programs instead of waiting until CD4 counts drop to a certain number—such as 200 or 350—to offer treatment.

Offering syringe exchange programs and medical-based treatment would also help. Russia, for example, has banned methadone clinics. Gay men—another population at higher risk for the virus—are persecuted in that country, putting them at further danger.

Pharris points out that success stories are not unheard of, but the trick is to build partnerships between local clinics, public health actions and community groups.

For related POZ articles, read “How Fake News and Homophobia Fuel HIV in Russia” and “The Other Russian Story: Its Silent HIV Epidemic.”

Comments

Comments