It has been almost 35 years since author Armistead Maupin, 63, first introduced the colorful cast of characters from 28 Barbary Lane to the world. What began as a soap opera-esque column—“Tales of the City” written for San Francisco newspapers, first the Pacific Sun and then the San Francisco Chronicle—evolved into six best-selling Tales of the City books and an award-winning PBS miniseries starring Olympia Dukakis and Laura Linney.

It has been almost 35 years since author Armistead Maupin, 63, first introduced the colorful cast of characters from 28 Barbary Lane to the world. What began as a soap opera-esque column—“Tales of the City” written for San Francisco newspapers, first the Pacific Sun and then the San Francisco Chronicle—evolved into six best-selling Tales of the City books and an award-winning PBS miniseries starring Olympia Dukakis and Laura Linney.

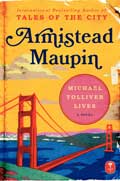

In his newest work, Michael Tolliver Lives, Maupin revisits the city by the bay to share the latest iteration of one of his most popular characters, Michael “Mouse” Tolliver. Although the location may be the same as in the previous six novels, things have changed: Most of the old crew has moved away, and the now 55-year-old Michael, who contracted HIV in his 30s and never believed he would make it to his senior years, has settled down with Ben, an HIV-negative man 22 years Michael’s junior. The story, told in the first person, gives the reader insight into the mind of an HIV-positive man who is experiencing the dramas of aging, the benefits of Viagra and the effects of his infuriating hyper-conservative Southern parents.

Maupin, who is HIV negative, chatted with POZ about his latest work, the early days of AIDS and the love of his life.

Kellee Terrell: What inspired you to write Michael Tolliver Lives?

Armistead Maupin: I have been thinking for some time about wanting to tell the story of HIV survivors. It seemed appropriate to return to Michael, because [there are] a lot of people in his situation—people who were expected to die years ago and who are now confronted with ordinary mortality. It fascinates me. The story examines the frustration of HIV survivors who still have parents out there somewhere, usually in the red states, but not always, who still don’t understand or accept the nature of their lives. In other words, parents who’ve remained homophobic in spite of a child who’s been living with AIDS for 20 years. And the rage that that can induce in a gay man. I think people have a right to be infuriated at their families at this point if they’re not accepting of homosexuality [or their AIDS diagnoses]. They’ve had far too long to become educated; any [reasons] they cling to at this point [for not accepting our sexual orientation or disease] are based on superstition and bigotry.

You walked the difficult line of not stigmatizing HIV by dropping it on the doorsteps of gay men, while making sure it still part of gay men’s narrative.

That was my challenge from the beginning. I was writing what was basically an entertaining tale. When AIDS came along and I lost one of my closest friends in 1982 (he was one of the earliest fatalities), I realized that I was going to have to incorporate AIDS into a story. But I wanted to do it in a way where AIDS didn’t overwhelm the narrative. I think that’s basically what [HIV-positive people] all have to do with our lives. Positive people have to deal with HIV every day but they also have to get on with the business of living and loving their lives. That’s the challenge, really. So if Michael Tolliver Lives is one way to show people how that might be done, I’m happy to have contributed to it.

The lives of other gay, HIV-positive writers such as Marlon Riggs and Paul Monette were cut short because they died of complications from AIDS in the ’90s. Are you carrying on their legacy?

I would be very proud to be considered to be carrying on their legacy. When I think of people like Paul and Marlon, I’m reminded how lucky I am to be alive and how important it is for me to appreciate my life and to celebrate the honor of growing older. I think it’s extremely bad taste to complain about getting old when you’ve been given that privilege that many of my friends were not.

Do younger HIV-positive people take for granted the struggle that the older generation had to go through with AIDS?

I think it’s true that any younger generation takes for granted things any older generation handled. It is very difficult to communicate the degree of panic—the sheer panic—that was prevalent in the early days of AIDS. All of us believed that we might die at any moment. We didn’t know what was causing the disease. And at the same time we were being blamed in the worst kind of way by the punitive forces of the [political] right.

I think there are younger people today who don’t understand exactly what battles [were fought] for them to be at the point where they can be cavalier about, say, barebacking. But I don’t blame anything on generations because I’m partnered with Christopher, a 35-year-old man who is an extremely responsible person who treats his HIV-positive diagnosis in the most serious way imaginable.

Why did you pick the treatment combo of the drugs Viramune and Combivir for Michael?

My husband, Christopher, was on the same combination when I started writing the novel.

Tell me about Christopher…

Well, he’s an extremely disciplined and conscientious man. He never lets me do anything that he thinks might endanger my health. If he’s just flossed, he won’t kiss me that night. It is sweet. I can’t think of a greater sign of love than caring as much about your partner’s health as you care about your own. He remains healthy through yoga and diet and exercise and his spiritual side is highly developed. He meditates everyday and he tries to be a good person and I think for all those reasons he’s on top of the disease. He is a wonderful person. For potential new fans who haven’t yet read any of your books, can they jump right in to Michael Tolliver Lives and not be lost?

For potential new fans who haven’t yet read any of your books, can they jump right in to Michael Tolliver Lives and not be lost?

You know, I’ve never written a novel—a Tales of the City novel—without first considering whether it would—and could—stand alone. I think you can pick up any of my books and enjoy the story. In Michael Tolliver Lives there are a number of places [where it] catches people up on characters that they might not know. And it’s largely set in the present, so I hope that people find themselves involved in that story.

Michael Tolliver Lives ($25.95, HarperCollins)

Another (HIV) Tale of the City

Legendary columnist and Tales of the City author Armistead Maupin returns with a long-awaited new installment, proving that his saga is as fierce a survivor as those who have survived AIDS.

Comments

Comments