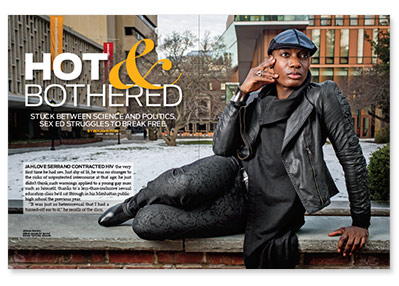

Jahlove Serrano contracted HIV the very first time he had sex. Just shy of 16, he was no stranger to the risks of unprotected intercourse at that age; he just didn’t think such warnings applied to a young gay man such as himself, thanks to a less-than-inclusive sexual education class he’d sat through in his Manhattan public high school the previous year.

“It was just so heterosexual that I had a turned-off ear to it,” he recalls of the class.

Today, at 27 years old, Serrano has come full circle. For the past four years, he has served on the speakers bureau of Love Heals, a New York City nonprofit that sends an army of HIV-positive, health-promoting foot soldiers into the area’s public schools to teach HIV prevention and to make up for what continues to be a critical educational deficit in school districts across the country.

After spending many years harboring anger toward a school system that failed him, Serrano now says, “I’m happy that I’m correcting some wrong that’s been done to me.” And yet, reflecting on the sex ed—or lack thereof—that schools are offering the kids he interacts with these days, he says, “It’s upsetting that the curriculum is still not even up to par and that it also doesn’t include the LGBTQ community.”

According to a 2012 survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 40 percent of elementary, 76 percent of middle and 82 percent of high school districts in the United States require HIV prevention education.

While New York has both an HIV education mandate dating back to 1987 and a relatively new middle and high school sex-ed mandate, the city serves as a prime example of how such mandates often represent a false front that masks a scattershot reality.

Corey Johnson, an HIV-positive New York City Council member who chairs the chamber’s health committee, says, “Currently, whether a student receives sex education is really dependent upon the individual principal’s interest and the particular school’s capacity to teach a sex-education class.” Newly elected, Johnson plans to advocate for improvements to the city’s performance in the sex-ed realm.

“Some schools are really beleaguered,” says Jasmine Nielsen, executive director of Love Heals. Repeating a refrain that is common among those who are pushing for improvements to sex-ed programs on a national scale, she says that the combination of strained budgets and an increasing focus on educational testing in public schools has crowded out not only such subjects as art or music, but sex ed as well.

In short, if it’s not on the test, it often doesn’t get taught. On that front, the Washington, DC, school district is a lone star for putting both sexual and HIV education on standardized tests; no states in the nation have similar policies. Many public health advocates are excited by the now-proven capacity for antiretrovirals to prevent transmission of the virus through pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP, giving HIV-negative people meds) and through “test and treat” (testing everyone for the virus and putting those who test positive on treatment so that their viral load is undetectable and unlikely to be transmitted).

Many public health advocates are excited by the now-proven capacity for antiretrovirals to prevent transmission of the virus through pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP and PEP, giving HIV-negative people meds) and through “test and treat” (testing everyone for the virus and putting those who test positive on treatment so that their viral load is undetectable and unlikely to be transmitted).

Yet other advocates are making a plea that we not forget the basics. The need for more effective prevention measures among young people in particular is profound. According to CDC surveillance data, Americans between the ages of 13 and 24 accounted for one in four of the estimated 50,000 new HIV cases in 2010, the most recent year for which data is available.

The data for youth of color makes for a starker picture. A third of all new HIV cases among blacks and 24 percent among Latinos were in this youth demographic in 2010, compared with 16 percent for the white population. For black men who have sex with men (MSM) such as Serrano, 45 percent of new HIV cases were in young people.

Most troublingly, young MSM (YMSM) made up 19 percent of all new HIV cases in 2010; and the rate of new HIV cases among YMSM increased by 22 percent between 2008 and 2010. In fact, this is one of the few demographics in which the rates have been climbing; overall, the number of new infections each year has been relatively stable the past decade.

“Certainly for YMSM of color, their HIV infection rates are criminally high,” says Monica Rodriguez, president and CEO of the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS). “We as a country and certainly as a school community are really negligent in our efforts to address this.”

Like the hot-button political wedge issues of abortion, stem cell research and end-of-life decision making, the matter of how American public schools should teach young people about sexuality has long been caught in the crosshairs between science and public policy.

Despite exhaustive research showing that dynamically designed comprehensive sex-education programs are successful at reducing sexual risk-taking among young people, the federal government has a tradition dating back more than three decades of lending support to abstinence-only-until-marriage programs.

After Bill Clinton opened a significant spigot for funding such programs when he signed welfare reform into law midway through his presidency, George W. Bush let loose a veritable flood of cash for abstinence-only, ultimately resulting in $1.7 billion between 1996 and the present that has been funneled into programs that have no basis in science.

The Obama administration, however, has overseen a significant turn-around: The annual budget of about $175 million that supported abstinence-only programs throughout the mid-2000s has since fallen to $55 million a year. Meanwhile, more than $200 million annually now goes toward much more comprehensive sex-ed programs that boast research backing up their efficacy.

“Things are actually much, much better now,” says Leslie Kantor, MPH, vice president of education at Planned Parenthood, which provides sex-ed workshops in schools across the country. “Science is helping to push good practice today in terms of researching whether programs work and then putting the money toward those.”

Particularly noteworthy is the fact that the CDC recently began partnerships with school districts in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Broward County, Florida, to target minority YMSM with HIV-prevention efforts within schools—a move sex-ed advocates say is profoundly overdue.

“It is unconscionable that until last year there was no evidence-based HIV intervention targeted specifically to YMSM under age 18,” says Debra Hauser, president of Advocates for Youth, a Washington, DC–based group that lobbies for effective sex-ed programs.

The school district of Broward County—home of Fort Lauderdale—is also notable for how seriously its leaders have taken recent news of disproportionately high rates of new HIV cases in the area. With a 2013 survey finding that 14 percent of high schoolers in the district never received any HIV education, the district is in the process of revamping its outdated sex-ed program and replacing it with a mandate for a comprehensive, up-to-date approach that spans kindergarten through high school.

On the other hand, 37 states currently require that schools provide students information on abstinence, with 25 of them stipulating that educators must stress the importance of abstinence, according to the Guttmacher Institute. Eight states have so-called “no homo promo” laws that forbid teachers from discussing LGBT issues positively. Three of those states—Texas, South Carolina and Alabama—require schools to teach exclusively negative information about homosexuality.

“The gulf between the rhetoric on the religious right and the science and even public opinion on this stuff is so wide,” says Johanna Miller, advocacy director at the New York Civil Liberties Union, who co-authored a recent report slamming New York State sex-ed programs for a litany of egregious deficiencies, harmful messages or out-of-date curricula and text books. “You know instantly this is all just a political game.”

Indeed, all of the tax payer dollars and policies supporting abstinence-only programs fly in the face of research that consistently shows that the overwhelming majority of American parents support comprehensive sex ed. The fear of scandal from a vocal minority often prevents sensible decision making on behalf of public school students. A recent Planned Parenthood poll found that 90 percent of parents believe that high school sex-ed programs should cover sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV. Seventy-five percent believe the same should be true for middle school education. Shame is often the cudgel used to deliver the sex-ed message. In 2011, Maddie Shepherd was a sophomore at a public high school in Birmingham, Alabama, when school officials reacted to high rates of syphilis in the area by assembling all the boys into the cafeteria and all the girls into the gym and then giving them each finger-wagging lectures on why they shouldn’t be having sex.

Shame is often the cudgel used to deliver the sex-ed message. In 2011, Maddie Shepherd was a sophomore at a public high school in Birmingham, Alabama, when school officials reacted to high rates of syphilis in the area by assembling all the boys into the cafeteria and all the girls into the gym and then giving them each finger-wagging lectures on why they shouldn’t be having sex.

“I was like, ‘Are you joking?’” says Shepherd, who is now 18 and a freshman at Barnard College in New York City. “‘People are obviously having sex, and you’re gathering them here after the fact, and you’re probably making them feel terrible about it.’”

Shepherd wasn’t prepared to sit idly by while she knew her school system wasn’t doing its job to properly prepare her peers and her for a healthy future. So this child of liberal parents joined a group of youth advocates that has been teaming with AIDS Alabama, an AIDS service organization based in Birmingham, to lobby the state government for improvements to the laws that govern sex ed.

Currently, Alabamian schools aren’t required to teach sex ed, but if they do they must emphasize various bullet points, including the notion that homosexuality “is not a lifestyle acceptable to the general public” and that abstinence “is the expected social standard for un-married school-age persons.”

As for what kind of instructions students in the state actually receive, AIDS Alabama’s fiery CEO, Kathie Hiers, quips, “A lot of the schools do what I jokingly call ‘drive-by sex ed.’”

Shepherd was bombarded with a slide show of graphic and horrific images of STIs, presented as common consequences of sex and not the worst-case scenarios that they most likely were. Then there was the lecture from the imported sex-ed teacher who, Shepherd recalls, “used the word ‘ho’ about five times in 30 seconds.”

In an attempt to teach the students about how wanton sexual behavior among both boys and girls could qualify a member of either sex as a “ho,” the woman was rather inartfully attempting to place a gender-equality cherry on top of her shame-based teaching.

“But I don’t think you should be calling anybody a ‘ho,’” Shepherd says. “That was a really low point in my sex ed. What high schoolers really need at that point in our lives is very level-headed education and a lot of facts, and that’s not what we were getting at all.” Another pervasive problem in sex-ed messaging lies in the credentials of the messengers themselves.

Another pervasive problem in sex-ed messaging lies in the credentials of the messengers themselves.

“We have a lot of educators who, while being well meaning, aren’t necessarily trained to provide sex education,” says Advocates for Youth’s Debra Hauser. “Few were required to study either the content or the pedagogy of sex education while in college.”

However, there is hope according to Leslie Kantor of Planned Parenthood, “The great news about HIV and sex education is that when it is done well it is taught in an extremely compelling way.”

Jason Villalobos, a 34-year-old HIV-positive substitute teacher, works to pick up where gym teachers leave off in his capacity as a guest speaker teaching HIV prevention on behalf of Planned Parenthood throughout the County of Santa Barbara, California, school district.

“The real challenge was: How do I wake these kids up from their slumber and make them realize that this is something to be concerned about?” he says.

Like Jahlove Serrano, who says his M.O. is to relate to kids on their level and speak with them in a language they can understand, Villalobos says he has been able to bridge the gap and get kids to key into his lessons about HIV by drawing parallels between discrimination he has suffered and the everyday slings and arrows of being a teenager.

Villalobos tells them about how men didn’t want to date him, about being rejected by his own Mexican community for his HIV-positive status, and also about being called a “wetback” as a child. It turns out that kids are well versed in the language of ostracism.

“Slowly, hands went up,” he recalls of the first time he tried this approach. “It was remarkable. In one class I had a young 16-year-old girl who came out to the class as being a victim of sexual assault. Another young man said that his favorite uncle was gay and had HIV and that he knew all about the disease.”

Serrano puts the key to success in no uncertain terms: “Education is education,” he says. “I mean, ‘HIV 101’ is just blah. But if you have somebody telling it like it is, in their language, it’s a different experience.”

2 Comments

2 Comments