Maintaining a program that provides broad-based HIV testing and prompt initiation of antiretroviral (ARV) treatment among those who have the virus would yield a substantial reduction in the new infection rate and also be cost effective. That is according to a new analysis of the PopART, or HPTN 071, trial that analyzed the effects of an intensive test-and-treat program in various communities in sub-Saharan Africa.

Successfully treating HIV eliminates the risk of transmission. Consequently, providing much more widespread ARV treatment and doing so earlier in the course of infection should, at least in theory, lower the overall rate of transmission in a community by reducing the period during which people with HIV have infectious virus.

Findings presented in March at the 2019 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in Seattle indicated that the intervention studied in PopART was associated with a reduction in new HIV cases, although this reduction was only statistically significant for one of the two levels of intervention studied.

Now the study has been published in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). Additionally, at the 10th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2019) last week in Mexico City, William Probert, PhD, an infectious disease modeling researcher at the Nuffield Department of Medicine at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, presented the results of a mathematical modeling study projecting into the future the effects and the cost effectiveness of the PopART test-and-treat program.

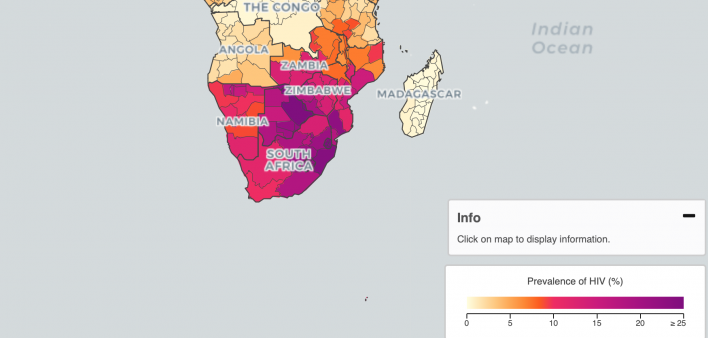

Between 2013 and 2018, the PopART investigators randomly divided 21 communities in Zambia and South Africa, with a combined population of about 1 million, into three groups of seven communities each. Group A received a combination HIV prevention intervention as well as universal access to ARV treatment. Group B received the intervention with HIV treatment provided according to local guidelines. Group C received the local standard of care.

The intervention included home-based HIV testing provided by community health workers and, for those who tested positive, linkage to medical care for HIV and assistance with adhering to the daily ARV regimen.

At the outset of the study, local guidelines stipulated that ARV treatment should be provided to those whose CD4 cells had declined to a certain point. In 2016, guidelines switched to recommend treatment to all those with HIV, regardless of their CD4 count. This shift complicated the PopART study as well as two other similar studies analyzing test-and-treat interventions in sub-Saharan Africa because they all effectively lost their control communities midway through their research.

Those other two studies, SEARCH and the Ya Tsie trial, or the Botswana Combination Prevention Project, were also just published in NEJM. In general, all three studies found that the test-and-treat programs reduced the rate of new HIV infections by about 30%.

PopART analyzed the HIV diagnosis rate in the 21 communities between months 12 and 36 of the study by analyzing approximately 2,000 randomly sampled people 18 to 44 years old per community—for a total of 48,301 people. They also assessed the proportion of those with HIV who had a viral load below 400 two years into the study.

At the study’s outset, the proportion of the community members in the three study groups who were living with HIV was between 21% and 22%. Between months 12 and 36 of the study, 553 people in the overall subpopulation of community members that received close monitoring tested positive for HIV, occurring during a 39,702 cumulative years of follow-up. This translated to an overall HIV infection rate of 1.4 new cases per 100 cumulative years of follow-up.

After adjusting the data for various factors, the investigators found that Group A had an HIV infection rate 7% lower than Group C, a difference that was not statistically significant, meaning it could have been driven by chance. Meanwhile, Group B’s infection rate was 30% lower than Group C’s, a difference that was indeed statistically significant.

This difference between the two pairs of relative outcomes has confounded researchers, as it is counterintuitive that the group that initially received more restrictive access to HIV treatment should have seen a significant decline in new cases of the virus while the group that received universal treatment access from the get-go should not have seen such a significant decline.

In Groups A, B and C, the proportion of those living with HIV who had a fully suppressed viral load at month 24 of the study was 71.9%, 67.5% and 60.2%, respectively. An estimated 81% of those in Group A and 80% in Group B were receiving ARVs 36 months into the study.

The mathematical modeling study presented at the Mexico City conference projected that the PopART intervention would lead to a 50% reduction in the annual HIV infection rate by 2030, compared with the lack of the intervention.

The home-based intervention package costs $5.10 to $6.80 in Zambia and $6.40 to $8.20 in South Africa per year per person older than 14 years old living in the communities studied. If such an intervention were continued through 2030, the cost to reduce one disability-adjusted life year, a composite of years of life lost and diminished quality of health, would be $465 to $847 in Zambia and between $503 and $922 in South Africa. Both ranges are considered cost effective.

To read a press release about the modeling analysis, click here.

To read the study abstract, click here.

1 Comment

1 Comment