Mario Cooper’s death on Friday morning, May 29, wasn’t a surprise and, from a conversation I had with him last month (when I was in Washington for AIDS Watch), I knew he was ready to let go. But it still hurts a lot. I will miss his love, his friendship, our holidays and travels together and I will miss his influence on my activism.

Mario had to leave his own activism years ago, when long-term neurological ramifications of HIV and debilitating depression led him to a much smaller world. No longer was he strategizing, organizing and invisibly manipulating levers of power to better our nation’s response to the epidemic.

Instead, he coped with a never-ending series of medical appointments, therapies and treatments that consistently failed him. He always suffered unselfishly, deflecting attention and concern from others, rarely uttering a syllable of complaint.

Most AIDS activists today have never heard of Mario Cooper (who was born February 8, 1954); even fewer understand the scope of his contributions over the years. He was innately modest and humble, preferring the behind-the-scenes role he played so perfectly.

But in the 1980s and 1990s, Mario was an extremely important link between grassroots AIDS activists and both the Democratic political establishment and many of the most important African American leaders in the U.S. He worked relentlessly and without compromise to convince powerful institutions and individuals to step up and do their share to support those on the front-lines of the epidemic.

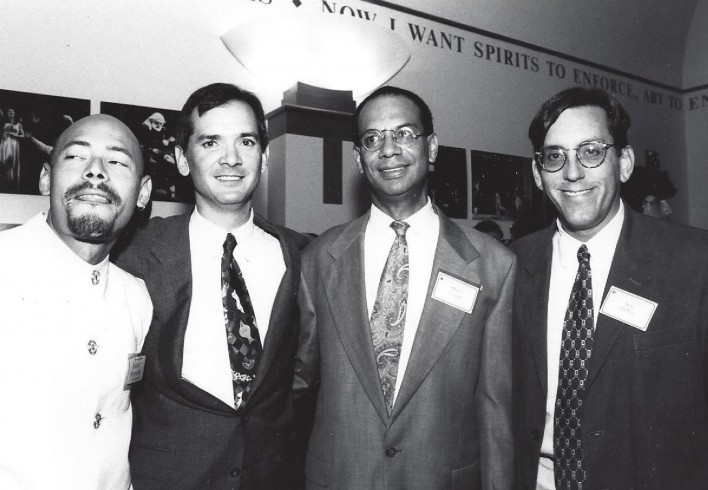

Xavier Morales, me, Mario and Bob Hattoy at the 1997 AIDS Action Council benefit in Washington.

Some of us had to learn our activist skills over time, but for Mario it was in his genes. He grew up in a family of political and social justice activists in Alabama who were deeply engaged in Democratic politics and the civil rights movement. One of his brothers was the first black man in Alabama to win an election unseating a white incumbent; another brother was Assistant Secretary of the Air Force and, later, the Ambassador to Jamaica; one of his sisters founded the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, DC, and was elected to the Washington, DC, school board, where she served as its President; a nephew is a federal judge.

Mario never knew a life different from one led at the nexus of Democratic politics, the civil rights movement and elite African-American intellectual and political circles. After attending Middlebury College, Mario went to work in Jimmy Carter’s White House, and then he got a law degree from Georgetown. Later he was deputy director of the Democratic National Committee and worked for Commerce Secretary Ron Brown. In 1992, he brilliantly managed the Democratic National Convention in New York City that nominated Bill Clinton.

Openly HIV+ Bob Hattoy (pictured above, on the right) addressed that convention, an opportunity Mario helped facilitate. At the time of the convention, Mario Cuomo was New York’s governor, which prompted New York magazine to headline a profile of Mario Cooper, “The Other Mario.” The year after Clinton was elected, Mario was the catalyst for an historic Oval Office meeting of gay and lesbian leaders with the President. Throughout the Clinton presidency, Mario and Bob Hattoy were the two most important inside-the-administration sources--some might label them “moles”--providing help and guidance to POZ, ACT UP and other AIDS activists.

Mario said he figured out he was gay when he was about 10 or 12 years old and had a crush on civil rights legend Julian Bond (pictured below), who stayed at the Cooper home in Alabama in the 1960s when Bond was a civil rights organizer. I don’t know when Mario came out to Julian Bond or anyone else--he was always out, since I first met him in the 1980s--but I’ve wondered what affect knowing gay men like Mario Cooper, as well as Bayard Rustin, had on Bond’s very early endorsement, in the 1970s, of the gay rights movement.

Julian Bond circa 1963.

In 1990, Mario joined the board of Washington’s Whitman Walker Clinic; later he served on the board of Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York. When he was elected as the first African American and first openly HIV positive board chair of AIDS Action Council (now AIDS United), AIDS was the #1 killer of African American men, and #2 killer of African American women, between the ages of 25 and 44. Mario, while he chaired AIDS Action Council, was a leader in the effort to change the formula for allocation of Ryan White funds so they would better meet the needs of the communities where the epidemic was headed (read: black, rural, poor) as well as the communities where the epidemic was already raging.

That led Mario to organize the Leading for Life campaign with the Harvard AIDS Institute (now Harvard AIDS Initiative), which kicked off in February of 1996 with an historic gathering of influential black academics, advocates and leaders in the arts, entertainment and business. I was honored when Mario invited me to participate. Leading for Life is recognized as having played a pivotal role in mobilizing African-American community leadership.

One of its first successes was when Bill Clinton finally declared the AIDS epidemic “a crisis” in communities of color and allocated $156 million in funding to combat it. Jacob Levenson, in The Secret Epidemic: The Story of AIDS and Black America, writes in detail about Mario’s role in this effort. When it was clear the funding was coming through, a reporter from the Washington Post called Mario for comment. “It’s a shot in the arm,” he said. But then he added, “It’s really only chump change for what is going to be needed for this disease.”

Me, Xavier and Mario in 2009 at the National Equality March on Washington.

Mario was also one of the first to recognize how the white gay community had started to leave the epidemic in favor of the tantalizing prospect of marriage equality. At the height of the battle to protect the anonymity of HIV testing and oppose mandatory reporting of the names of those testing positive to the government, Mario wrote:

“As my white gay brothers and lesbian sisters couch their claim of equality in the warm radiance of the Civil Rights Movement, they also seem willing to walk away from AIDS as it extends its grip on other, nonwhite communities. One gay activist I know even had the nerve to announce that names reporting was no longer ”that big of a deal“ because ”those“ people are used to being manipulated by society.”

Mario stopped using email regularly several years ago, but in one of our last email exchanges, I told him about Sero’s efforts to organize people with HIV and create more and stronger networks of people with HIV, to enable us to define our own agenda, select leaders of our own choosing and speak with a collective voice. He wrote back, "I’ve got only one thing to say, but Harriet Tubman said it first: ’I freed a thousand slaves; I could have freed a thousand more if only they knew they were slaves.’"

Note: Upon learning of Cooper’s passing, other leaders of the HIV/AIDS community have reflected on his legacy. Several remembrances are collected in the POZ web exclusive "In Memoriam: Mario Cooper."

To read his New York Times obituary, click here.

7 Comments

7 Comments