“We have the tools to end the HIV epidemic.”

During the current decade, this refrain has come into vogue among members of the HIV prevention, treatment, research and advocacy community.

The expression refers to the awesome power of what’s known as biomedical prevention of HIV. As research that has emerged since 2010 has made crystal clear, not only does fully suppressing the virus with antiretrovirals (ARVs) block transmission, but when HIV-negative people take daily pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), they reduce their risk of acquiring the virus by more than 99%.

Descovy and Truvada, the two drugs approved for use as PrEP

So, at least in theory, applying these tools on a grand scale could end the global HIV epidemic.

In theory.

The reality is much more complicated, given in particular the myriad complexities of getting tens of millions of people living with and at risk for HIV on daily ARVs.

“We don’t live in a theoretical world; we live in a real world,” says Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Anthony Fauci, head of NIAID, at the 2019 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in SeattleBenjamin Ryan

Consequently, those who utter the line about having the tools to end HIV invariably follow the statement with a sentence that begins “But….”

Seeking to address the obstacles impeding global progress toward ending the virus as a public health threat, Fauci and his colleagues published a paper in Clinical Infectious Diseases on October 24 outlining the numerous promising opportunities for optimizing HIV treatment and prevention tools around the world in the years to come.

As Fauci and his coauthors note, between 1995 and 2015, ARV treatment averted an estimated 9.5 million AIDS-related deaths and 7.9 million HIV transmissions around the world.

Source: UNAIDS

Source: UNAIDS

Source: UNAIDS

That’s the good news.

The sobering counterpoint to those statistics is the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimate that in 2018, some 38 million people were living with HIV and 1.7 million individuals contracted the virus.

Despite the global consensus reached in 2015 that all people with the virus should be granted access to ARVs regardless of CD4 count, today just 23 million, or 60% of the global HIV population, is on treatment for the virus. And although AIDS-related deaths have declined by more than 55% since peaking in 2004, 770,000 such deaths still occurred worldwide last year.

Source: UNAIDS

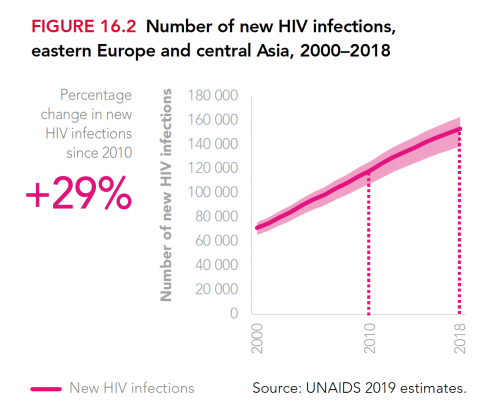

What’s more, the global annual HIV transmission rate has declined by less than 2% per year since 2010. Granted, this across-the-board statistic masks the fact that HIV is fast declining in southern and eastern Africa—a feat that warrants considerable celebration. However, new cases of the virus are rising in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, including Russia, apparently driven in by injection drug use in particular.

Source: UNAIDS

Source: UNAIDS

Source: UNAIDS

“Even though we want to continue to make innovative advances in different types of therapies and prevention,” Fauci says, “the critical issue is the implementation gap, in testing, in treatment in retention in care, in viral suppression, in food and housing security, in prevention and harm reduction, in stigma and human rights. We’ve got a long way to go.”

Concerningly, only about 60% of people who begin ARV treatment for HIV in low- and middle-income nations are still on therapy four years later.

Additionally, while it is considerably challenging to establish precise, up-to-date estimates of global PrEP use, as of April 2019, only perhaps 475,000 people were taking Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine) for HIV prevention. (Descovy [tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine] has since been approved in the United States as a new form of PrEP.) The United Nations has called for 3 million people to get on the HIV prevention pill by 2020.

About a quarter to a half of global PrEP users are in the United States, where PrEP was approved in 2012. In the United States and elsewhere, PrEP use has been linked to declining HIV rates. Notably, Australia has seen a highly impactful surge in PrEP use since 2016.

The major push to treat HIV in Africa began in the early to mid-aughts, thanks in large part to President George W. Bush’s launch of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Continued efforts by PEPFAR and The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria have yielded impressive advances on this front in recent years.

Notably, in 2017, PEPFAR-driven research indicated that in hard-hit Swaziland, a five-year doubling of ARV treatment use coincided with an approximate halving of the annual rate of new infections.

Such real-world evidence of the impact of HIV treatment as prevention notwithstanding, a recent trio of important randomized controlled studies of testing and treatment programs in sub-Saharan Africa, which were presented at the 10th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2019) in Mexico City in July, reached cloudy conclusions about the power of ARVs to curb transmissions of the virus on a grand scale.

In general, the studies found that such programs reduced the HIV transmission rate in a particular area by about 30%—a respectable but not necessarily epidemic-ending effect. The research also yielded contradictory findings, with one particular subpopulation assessed in a study called PopArt achieving no apparent HIV prevention benefit from an aggressive test-and-treat program.

Alone as a prevention method, scaling up HIV testing and treatment, Fauci says, doesn’t have the hoped-for dramatic impact on infection rates “because of the discordance between the people you’re treating and the people who are driving the epidemic.”

In other words, much of the world’s HIV transmission is likely driven by individuals who are missed by test-and-treat efforts and otherwise occurs during the early phase of individuals’ infection, when their viral load is very high and they have not yet been diagnosed.

The Clinical Infectious Disease paper also points to significant success stories in municipal efforts to drive local HIV epidemics into retreat. In San Francisco, a muscular, well-coordinated and, importantly, well-funded citywide effort has driven up rates of HIV testing and treatment as well as PrEP use. Critically, the campaign has succeeded in getting people newly diagnosed with the virus on treatment much faster—often within hours—thus reducing the time during which their virus is transmissible.

Between 2006 and 2018, the Bay Area city’s HIV diagnosis rate declined by 63%.

Courtesy of San Francisco Department of Public Health

New York City just announced continued impressive progress in scaling back its own epidemic, with an estimated 40% five-year decline in new transmissions. London has also dramatically lowered its new infection rate in recent years.

Source: NYC DoHMH

Source: NYC DoHMH

“We know that if you maximally implement the tools you can get results,” Fauci says.

But can such cities success serve as models for other cities and nations around the world? Or are the circumstances of such wealthy places inapplicable to the effort to drive up HIV treatment rates in Atlanta, Moscow or Cape Town?

Worldwide, uptake of ARV treatment, Fauci and colleagues write, “remains suboptimal because of adherence challenges, including those related to substance abuse, housing deficits, pill fatigue, drug toxicity, stigma and discrimination.”

A long-acting injectable HIV treatment may provide a potential answer to the thorny question of how best to support adherence to ARV regimens. The first such regimen, Cabenuva (cabotegravir/rilpivirine), is poised for approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), likely by the end of 2019. The treatment requires visiting a clinic every four weeks to receive an injection.

Long-acting antibody injections are also making their way through the pipeline, for both HIV treatment and PrEP.

Then there is the hope for an HIV cure. These days, as research increasingly suggests that full eradication of the virus within the body will prove extraordinarily difficult in all but rare cases, experts in this arena tend to characterize their research as seeking to establish “long-term remission” from HIV or “durable control of the virus” in individuals without the need for standard, ongoing ARV treatment.

Scientists in the field generally believe they have a long road ahead before they may succeed in developing effective, widely applicable therapies. That said, numerous investigational treatments currently in various stages of development may realize incremental success in this arena during the 2020s.

In the meantime, as Bill Gates said at the International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa, in 2016, “We’re not going to treat our way out of this epidemic.”

Optimizing the HIV prevention tool kit, Fauci and colleagues state in their paper, “will require innovative approaches” in the realms of both PrEP and vaccines.

“The holy grail of everything is to develop a vaccine,” according to Fauci—even more so, he says, than finding a cure for the virus.

This is actually an exciting time for vaccine research. Two major trials of promising vaccine candidates are well under way in sub-Saharan Africa, and a third in Europe and the Americas, called Mosaico, recently began a soft launch, with full-scale enrollment beginning in the coming weeks. Researchers behind the trials are cautiously optimistic that by the middle of the coming decade, the world may finally see an at least moderately efficacious HIV vaccine.

The planned Mosaico sites

The hope is to find a vaccine that reduces the risk of contracting HIV by at least 50%, which, according to Fauci, would justify a broad rollout.

A recent mathematical modeling study projected that if there were no additional progress in HIV treatment and prevention efforts—which, granted, is an improbably dire real-world outcome—nearly 50 million people around the world would contract HIV between 2015 and 2035. A vaccine that cut HIV risk in half could avert about 35% of those new cases, according to the modeling.

As for PrEP optimization, researchers are fast at work investigating long-acting injectables that could cut PrEP dosing schedules down to as seldom as once every six months as well as ARV-infused implants that prevent HIV acquisition that could require dosing only once a year.

Microbicides against HIV have been plagued by considerable controversy over the past couple of years. This form of prevention includes ARV-containing products for insertion into the vagina in the form of sponges, gels, creams, rings or suppositories or into the rectum through enemas, gels, creams or lubricants.

Research in this field has suffered a series of major setbacks. That said, there remain numerous experimental microbicides that could prove a useful addition to the HIV prevention armamentarium. Notably, a monthly vaginal ring infused with the ARV dapivirine has proved moderately effective and is poised for regulatory approval.

A woman holds the dapivirine vaginal ringAndrew Loxley, courtesy of the International Partnership for Microbicides

“People need choices for HIV prevention, so they can find the option that works best for them,” says Jared Baeten, MD, PhD, a professor of global health, medicine and epidemiology at the University of Washington in Seattle, who led the research into the ring. “The dapivirine ring offers a real and powerful choice: a safe prevention option that is completely under a woman’s control. It has huge potential for impact, particularly for women in Africa, where PrEP uptake has been slow, in part due to the demands of taking a pill every day.

Jared Baeten at the 2016 Conference on Retorviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Seattle, having just announced the first major findings supporting the vaginal ring’s effiacyCourtesy of Benjamin Ryan

Such promise and success in the overall microbicides field notwithstanding, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) recently indicated that going forward, it would view microbicides with a more discerning eye vis-à-vis research priorities. Since the NIH is the dominant player in this global research field, if the federal agency pulls its financial support, the remainder of the microbicide pipeline could be reduced to a footnote in the history of the fight against HIV.

Microbicide development is essentially paying the price for daily oral PrEP’s success. Late to the party, experimental microbicides would face a very high bar in advanced clinical trials given they would be measured against the efficacy of taking daily Truvada or Descovy for HIV prevention.

Carl W. Dieffenbach, PhD, the director of the Division of AIDS at the NIH has made clear that he favors HIV prevention methods that provide protection against the virus throughout the body and not just at a single anatomical site. His position has, to say the least, deeply frustrated microbicide advocates and researchers.

Carl DieffenbachCourtesy of DAIDS

All this is not to say that new microbicides have necessarily met their death knell. Dieffenbach and Fauci alike have indicated that if such an investigational product does make impressive strides in early research, the NIH would support its ongoing development.

Summing up the grand challenges at hand as the globe stands on the cusp of a new decade and AIDS approaches its 40th birthday in 2021, Fauci says, “If we really want to end the epidemic, we have to optimize our HIV treatment and prevention tool kit in two arenas. The first is maximally implementing existing tools we have. And we know it can be done. Then, on the other side of the coin, if you maximally develop new and improved tools, both in treatment and prevention, you can also go a long way to ending the epidemic.”

Benjamin Ryan (benryan.net) is POZ’s editor at large, responsible for HIV science reporting. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

5 Comments

5 Comments